History of Indian-White Relations

Module 2

The history of the relationship between Southwestern Indians and non-Indian people began in 1539, when the first non-Indian made contact with the Zuni people of northern New Mexico. This first encounter ended in conflict, and foreshadowed the tensions that were to continue between Native American people and the Spaniards, Mexicans, and Anglos in the following centuries. In this module, you will learn about the history of these relations and explore how the policies and events of the intruding cultures impacted Native Americans.

At the end of this module you will be familar with the following terms:

Click next page to continue.

Trimble pp. 1-34 (PDF document)

Griffin-Pierce pp.17-28

The following video segments from "The People The West" a film by Steve Ives (select link, if the video box doesn't appear below,asking you to log into UNLV Library. The video will be streaming through UNLV Library). NOTE: You will have to use your ACE account or your activated RebelCard Barcode and PIN. Please see the "Let's Get Started" course module to get more instruction on accessing library materials from off-campus.

Watch the video for the following segments:

These are optional resources available to you to watch on tribal sovereignty and Carlisle Indian School.

Tribal sovereignty

Carlisle Indian School

Click next page to continue.

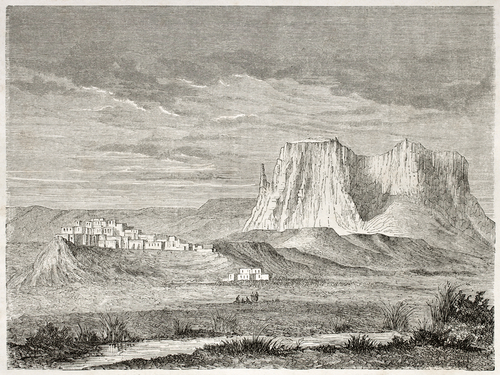

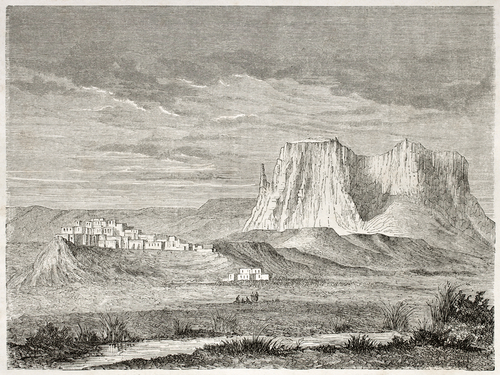

The first contact between Native Americans of the Southwestern United States and "Europeans" occurred in 1539. The first contact actually was not with any Europeans, but was with a black slave named Esteban (or alternatively as Estevancio) who was accompanying the Spaniard Fray Marcos de Niza in his search for Cibola, the legendary city of gold. Esteban, who was sent ahead as a scout, arrived at the pueblo town of Zuni, but (the story is told) after he demanded tribute and women, he was summarily murdered. After Esteban's murder, de Niza turned back to Mexico without making contact with the Native Americans, though upon his return to Mexico he stated that he had, indeed, observed Cibola and that the stories were true—that the entire town was indeed made of gold. Historians differ as to why de Niza reported this- the skeptical opinion is that de Niza out and out fabricated the account; a more generous viewpoint is that he observed the town of Zuni from afar, and that—with the sunlight glinting off of its adobe walls- the town indeed appeared to have been made of gold.

Zuni as it might have appeared to de Niza

Click next page to continue.

The next contact was made by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who set out in 1540 to relocate Zuni, the city of gold. After finally arriving at Zuni and realizing that there was no gold there, he and his men reportedly cursed de Niza—but continued to travel the region for another two years in an effort to locate the fabeled Cibola. Eventually, he returned home empty-handed and in deep disgrace.

Refer to "The People The West" video (select link, if the video doesn't appear below, asking you to log into UNLV Library. The video will be streaming through UNLV Library) to watch the portion on Coronado vs. Zuni Tribe, segment 14 (2:43 minutes).

Click next page to continue.

Spanish interest in the region continued, however, and in 1598 the first permanent settlement was established in the Rio Grande valley of northern New Mexico.

This settlement was established with two goals in mind:

(1) to Christianize the Indians, and

(2) to find gold.

When the latter did not happen, the Spaniards developed other means of support. The Spanish crown divided up the lands in the region, giving the tribes land grants, and giving rights to other lands to conquistadors and other settlers.

Two very unpopular policies were instituted:

(1)The ecomienda (tribute) and

(2)The repartimiento (forced labor).

Under the system of encomienda, conquistadors or other colonists were given rights over a specified number of Native Americans, from whom they could extract tribute (in the form of foodstuffs, craft products, etc). Under the system of repartimiento, Native Americans were required to work a certain number of days for the colonists tending their plantations, constructing their buildings, etc. These two policies resulted in severe hardships for the Indians, and created widespread subsistence stress and starvation among the indigenous people. Relations between the Rio Grande tribes and the Spaniards—while never good- worsened in 1598, when Spanish soldiers demanded tribute from the Native American village of Acoma, which was already reeling from food shortages caused by the encomienda and repartimiento systems. The villagers of Acoma refused and killed the soldiers. In retaliation, the Spaniards captured 500 Acoma men (all the men over 25 years of age) and sentenced them to the amputation of one foot and 20 years of servitude. All other Acoma Indians over the age of 12 were sentenced to 20 years of servitude as well.

Over the next century, relations with the Pueblo Indians worsened. Friars with the Roman Catholic Church reported that they had succeeded in converting all the Pueblo people to the Catholic religion; however, this was "accomplished" by rather brutal methods, including whipping anyone caught practicing their indigenous religion and then tarring the wounds with hot turpentine. In the late 1660s and 1670s, the friars raided kivas and destroyed Pueblo religious paraphernalia, and killed and whipped Indians accused of witchcraft. As a result, beginning in the 1670s, the Pueblo religious leaders began to discuss the possibility of a revolt. Popé, one of the Indians who had been flogged for sorcery, orchestrated the revolt and on August 10, 1680, the pueblos acted in concert to expel the Spaniards. The resulting battle ended with the death of more than 400 Spaniards, after which time the remaining 2,350 colonists fled the area. The Spaniards remained in exile for the next twelve years, until they retook the northern New Mexico in 1692.

Refer to "The People The West" video (select link, if the video doesn't appear below, asking you to log into UNLV Library.The video will be streaming through UNLV Library) to watch the portion on Pueblo Hardship vs. Dissent, segment 18 (1:34 minutes) and Pueblo Revolt and Spanish Return, segment 19 (3:06 minutes).

Click next page to continue.

By 1853, the entirety of what we now call the Southwestern United States was under the control of the U.S. The United States recognized the Spanish land grants, and thus the Indian groups along the Rio Grande retained their land grant rights. However, other tribes had constant encroachment on their lands. With the discovery of gold in the west, and the expansion of settlers westward, conflict between the U.S. and tribes was inevitable. Much of the problem stems from the fact that the land appeared "empty" and "unused" by the Anglos; however, these seemingly "vacant" tracts of land were important hunting and gathering lands used by the semi-nomadic tribes that lived in much of the area. As Native Americans lost access to these areas, they increasingly turned to raiding of Anglo mining camps and settlements as an economic mainstay. The U.S. Army retalitated with campaigns to subdue the tribes.

By the late 1800s, most tribes had signed treaties with the U.S. government in which they promised to cease raiding and warfare and to relinquish their claims to the lands. In return, the U.S. promised to

(a) set aside reservation lands for the tribe,

(b) provide certain forms of government assistance, and

(c) recognize tribes as sovereign entities.

Thus, it is from these treaties that the concept of tribal sovereignty derives. Although most Americans are unfamiliar with the concept, tribal sovereignty means that Native Americans have the right to govern themselves, and that reservation lands are not subject to state laws. (This is why reservations can operate casinos, even in states where casinos are illegal). Tribes are not fully equivalent to foreign sovereign nations, however—their rights can be limited by Congress, but only by Congress. (Note: today, Native Americans are considered citizens of both the U.S. and their own tribe. Like all other U.S. citizens, they pay taxes, have the right to vote, can serve in the military, etc. Tribal sovereignty simply means that the tribes have the right of self-governance within the boundaries of the reservation.). Tribes continue today to receive certain types of assistance from the U.S. government (for example, in health and education matters) as a result of the terms of these treaties, which required the U.S. to do so.

|

Members of federally recognized tribes have something akin to (though not exactly like) a dual citizenship. They retain membership in their sovereign tribe as well as enjoy the full rights and responsibilities of any other United States citizen. |

By the 1880s, virtually all Southwestern tribes were confined to either reservation lands or the Spanish land grant areas. However, there was a growing dissatisfaction of this policy that had encouraged Native Americans to live separately from and remain separate from the remainder of the U.S. society. For a variety of reasons (which we shall discuss in coming modules), making a living was difficult on most reservations, and few Native Americans had achieved self-sufficiency. They relied, instead, on government assistance (which was required as a part of the treaty agreements).

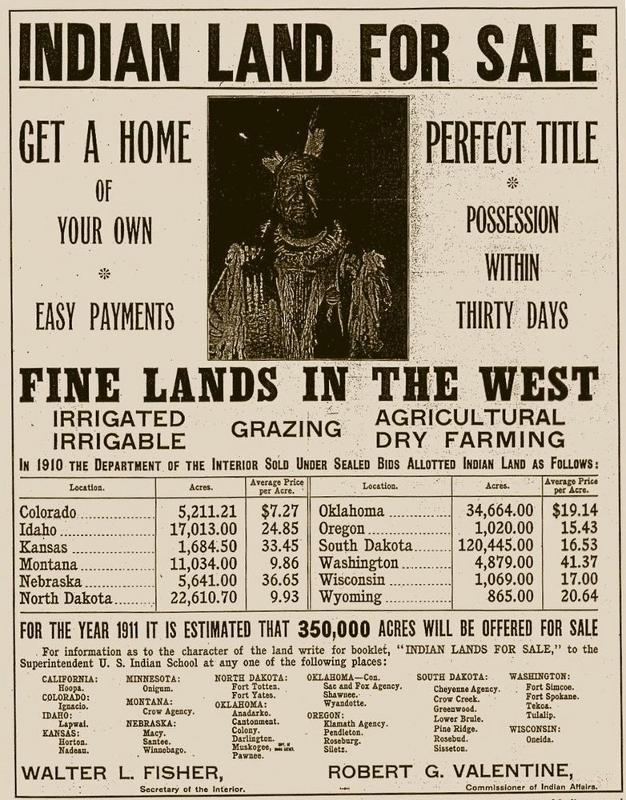

Thus, in the 1880s U.S. policy toward Native Americans shifted from one of separation (i.e., keeping Indians on the reservation) toward one of assimilation and acculturation. Reflecting this shift, in 1887 the Dawes Act was passed. This act gave the President of the United States the power to allot the lands within reservations to Native Americans and to sale off surplus reservation lands to non-Indians. This act was probably well intentioned- the goal was to replace the Indian concept of communally held lands with that of private property, with the idea that Indians would better prosper if they adopted Anglo concepts and values. However, the Dawes Act was devastating to tribes-- some tribes lost as much as 60% of their lands to non-Indians as a result.

Source:By United States Department of the Interior [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

http://hrmdeborah.blogspot.com/2009/02/geronimos-kin-sue-skull-and-bones-over.html

Click next page to continue.

|

Another means by which Indians were to be acculturated was through the creation of boarding schools, which Indian children were forced to attend. One such school was the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania. Children were forcibly removed from their families and sent away to these schools, which were often hundreds of miles from their homes; many children would not see their families again for several years. At the schools, Indian children were acculturated to Anglo ways—they were given English names and taught to speak English, practice Christianity, and dress in western attire. Any students caught speaking their native language or practicing native traditions would often be severely punished. The goal—to "civilize" Indian children by removing all traces of their native culture-- was succinctly stated by the founder of the Carlisle School, who wrote "kill the Indian, and save the man." |

|

Carlisle Boys and Girls in School Uniform, Dormitories in Background 1879 Source: Photo Lot 81-12 06805000, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution |

|

|

|

|

Portrait of Tom Torlino, in Partial Native Dress and Wearing Silver Cross Necklace 1882 |

Tom Torlino in 1885

|

|

Because the goal of the Carlisle School was to remove all traces of native culture, administrators typically photographed the children upon their arrival at the school and again a few months later to demonstrate their "progress" and improved appearance. These photos are of Tom Torlino, a Navajo youth, taken in 1886. The student file for Tom Torlino can be found at http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/student_files/tom-torlino-student-file |

|

|

Source: Photo Lot 81-12 06805000, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution |

Source: Photo Lot 81-12 06805000, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution |

Click next page to continue.

|

|

The allotment system was ended by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which also solidified tribal rights to self-rule and supported the freedom of Native Americans to practice their own religions. This ushered in a period of self-rule for Native American tribes. However, this period was not to last—after World War II, a new sense of nationalism emerged and some extreme conservatives saw Native American sovereignty as a threat to U.S. sovereignty. (Remember: this is the McCarthy era!). In 1953, termination became the official policy of the U.S., when a resolution designed to "free Indians" (from reservation lands and tribal rule) unanimously passed Congress. More than 100 tribes lost their reservation lands from this process, though only one tribe—the Southern Paiute bands in Utah—in the Southwest was affected. The U.S. spent a million dollars to relocate Indians from reservations to cities, and did away with the tribal sovereignty rights.

In the 1960s, the pendulum swung back the other way, and the policy of termination was overturned by Richard Nixon (who, interestingly, had a record of supporting and expanding Native American rights). Since that time, there have been numerous laws and presidential proclamations passed supporting the rights of tribal sovereignty, and acknowledging the special relationships of Native Americans to the U.S. government. |