The Pueblos

Module 3

Introduction

|

|

The people that we group together as Puebloan do not today, and never have, constituted a single tribal entity. Instead, they come from a diversity of backgrounds and speak a variety of mutually unintelligible languages. Nonetheless they all share broadly similar subsistence, settlement, and social organizational patterns. The Pueblo people can trace their heritage back in a more or less unbroken chain to about the time of Christ. As did their ancestors, many modern Pueblo people live in compact apartment-style buildings and emphasize farming activities. In this module, you will learn about the background of the Puebloan people, how the environment and European contact have impacted their lifestyles, the regional variations exhibited between the different Puebloan groups, and some of the current issues facing the modern-day Pueblo Indians

|

Required Readings

Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to describe the regional variations that characterize the different Pueblo groups in terms of environmental setting, language, social organization, and political organization

- Students will be able to identify how environmental differences and differences in the nature of the contact with Europeans have resulted in different subsistence and social organizations among the Western, Eastern, and Keresan Bridge pueblos

- Students will be able to identify major issues facing the Puebloan people today

- Students will be able to define major terms and concepts relevant to understanding Puebloan cultures

Recommended Readings

http://www.sacredland.org/index.html@p=468.html - this provides information on the Taos Blue Lake issue.

Major Concepts and Terms

- Pueblo

- Kiva

- Floodwater farming

- Dry farming

- Medicine societies

- Moieties

- Clan

- Lineage

- Matrilineal

- Bilateral

- Compartmentalization

- Blue Lake

- Kachina cult

- Sodality

- Winters Doctrine

Click next page to continue.

Prehistoric and History Page 1

|

|

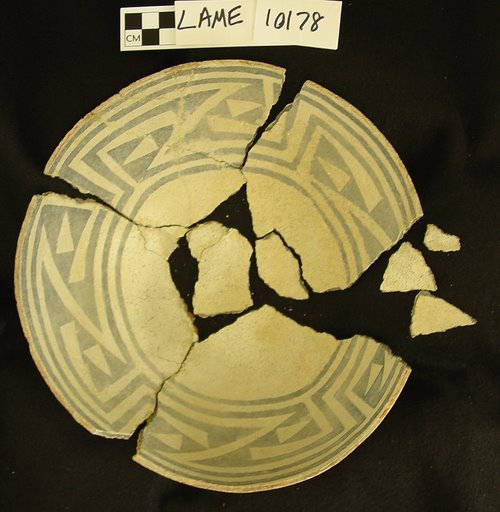

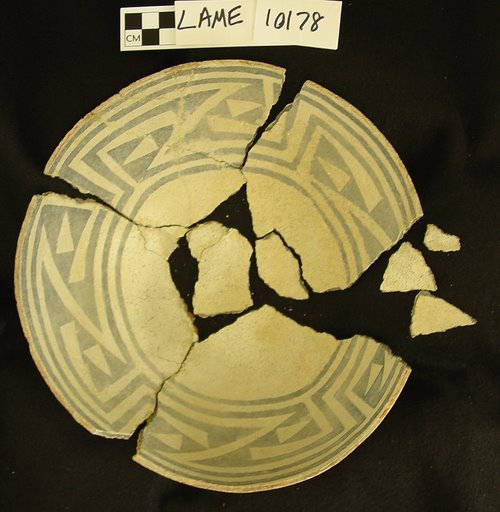

Although the "Puebloan people" come from diverse backgrounds, and even speak different languages from one another, all can trace their history in the American Southwest back to at least the time of Christ. Their archaeological predecessors are popularly known as the Anasazi or Mogollon, though most Native Americans prefer the term "Ancestral Puebloan" for these people. Archaeologically, the Puebloan culture is recognized by the presence of three traits: (a) a dependence on agriculture (primarily corn); (b) the use of a similar architectural style, and (c) the production and use of what is often intricately painted pottery.

|

|

A black-on-white bowl dating to about A.D. 1100, recovered from a puebloan archaeological site located near Logandale, Nevada

|

|

|

Since at least 900 A.D., most prehistoric Puebloan people lived in above-ground, contiguous rooms. After about A.D. 1300, the people aggregated into large, often multi-storied apartment-style buildings in villages that housed 1000 or more people

|

|

|

|

Cliff Palace, an Ancestral Puebloan ruin dating to the early 13th century A.D. in southwestern Colorado

Source - Shutterstock Image ID:130869356

|

|

.jpg)

|

Along major rivers where water was plentiful, these houses tended to be constructed of adobe, but elsewhere they might be constructed of sandstone slabs or other rock. They also had semi-subterranean structures, termed kivas, that functioned as religious chambers

|

|

Prehistoric kiva, after excavation.

Source - Shutterstock #Image ID:55035286

|

|

|

|

|

Reconstructed kiva interior

Source - Shutterstock Image ID:39205027

|

|

When the Spanish arrived, they found approximately 40,000 Puebloan people living in about 90 villages. (Today, about 30 of these villages survive). As did their prehistoric predecessors, the historic Pueblo Indians lived in apartment-style structures; grew corn, beans, squash and tobacco; made pottery; and conducted ritual activities in kivas.

|

|

|

|

Toas Pueblo, one of the Puebloan villages encountered by the Spaniards that is still occupied today.

Source - Shutterstock Image ID:60190786

|

|

Because they lived in aggregated villages, the Spaniards called them "puebloans," which is Spanish for "town-dweller." Soon after contact, most pueboan villages received title to their land from the Spanish crown through land grants, which continue to be recognized today by the U.S. government. Thus, unlike some tribes, the Puebloan people largely live in the same areas as they did at contact (and even into prehistory).

|

Click next page to continue.

Prehistoric and History Page 2

At the time of contact, the Puebloan people were largely aggregated along the Rio Grande river in northern New Mexico although some groups, such as the Hopi and the Zuni, were found further to the west away from the major watercourses. These geographical differences resulted in differences in how European contact impacted the people. While the Europeans were drawn to the lush, irrigable Rio Grande river valley, they had little use for or interest in the arid regions where Hopi and Zuni were situated. Thus, the pueblos located in the Rio Grande region were impacted to a much larger degree by contact than were the Hopi and Zuni. In particular, these eastern pueblos received the brunt of the Spanish attempts to eradicate their religion. The eastern pueblos responded by adopting the Catholic religion, but by continuing to practice their indigenous rites in secret (primarily in their underground kivas). This system—where both Catholic and traditional religious systems exist, but are practiced in two totally different spheres- is known as compartmentalism. The western pueblos were less influenced by Catholicism, and after the Pueblo Revolt they discarded most of the Catholic veneer and returned to their indigenous religion.

Langage Groups

There are four different linguistic stocks represented by the Puebloan languages. These are Uto-Aztecan (spoken by the Hopi), Zuni (spoken by the Zuni), Keresan (spoken by several villages located along the Rio Grande and to its west), and the Tanoan languages (Tiwa, Tewa, and Towa), spoken by a variety of pueblos located along the Rio Grande and elsewhere in northern New Mexico. These four different language stocks contain mutually unintelligible languages.

Instructions - Select the  icon at the bottom right hand corner of the page to learn more.

icon at the bottom right hand corner of the page to learn more.

Click next page to continue.

World View

The Puebloan people were never integrated into a single tribe or political system. Rather, each village traditionally acted as an autonomous political unit. The villages, however, commonly interacted with one another during trading fairs, ceremonies, and other social events.

Despite their language differences, the various Puebloan villages all tend to share a common world view. In Puebloan society cooperation is valued, and shows of individualism are condemned. All individuals are expected to participate in communal activities such as repairing communal structures or irrigation canals, or participating in communal rituals. Social control is enforced largely through the mechanisms of gossip and public ridicule.

The Pueblo people believe that there exists a reciprocal relationship between humans and nature. That is to say, the actions of humans are believed to influence those of nature, and vice-versa. Thus, humans are dependent upon nature to survive, but nature, in turn, is dependent on humans as well. If humans do not perform the right rituals and have the right attitude, this can cause disequilibrium in the universe and can, for example, keep the rains—so needed for the crops-- from coming. All Puebloan people also share a similar belief in how they came to be in this world. Athough variations exist in the origin stories, all believe that their ancestors emerged into this world from the underworld.

|

|

|

|

Painting of Hopi dancers, wearing traditional ceremonial costumes

Source - Image ID:219485458, meunierd / Shutterstock.com

|

Painting of styled Hopi kachinas

Source - Image ID:21948525, meunierd / Shutterstock.com

|

Click next page to continue.

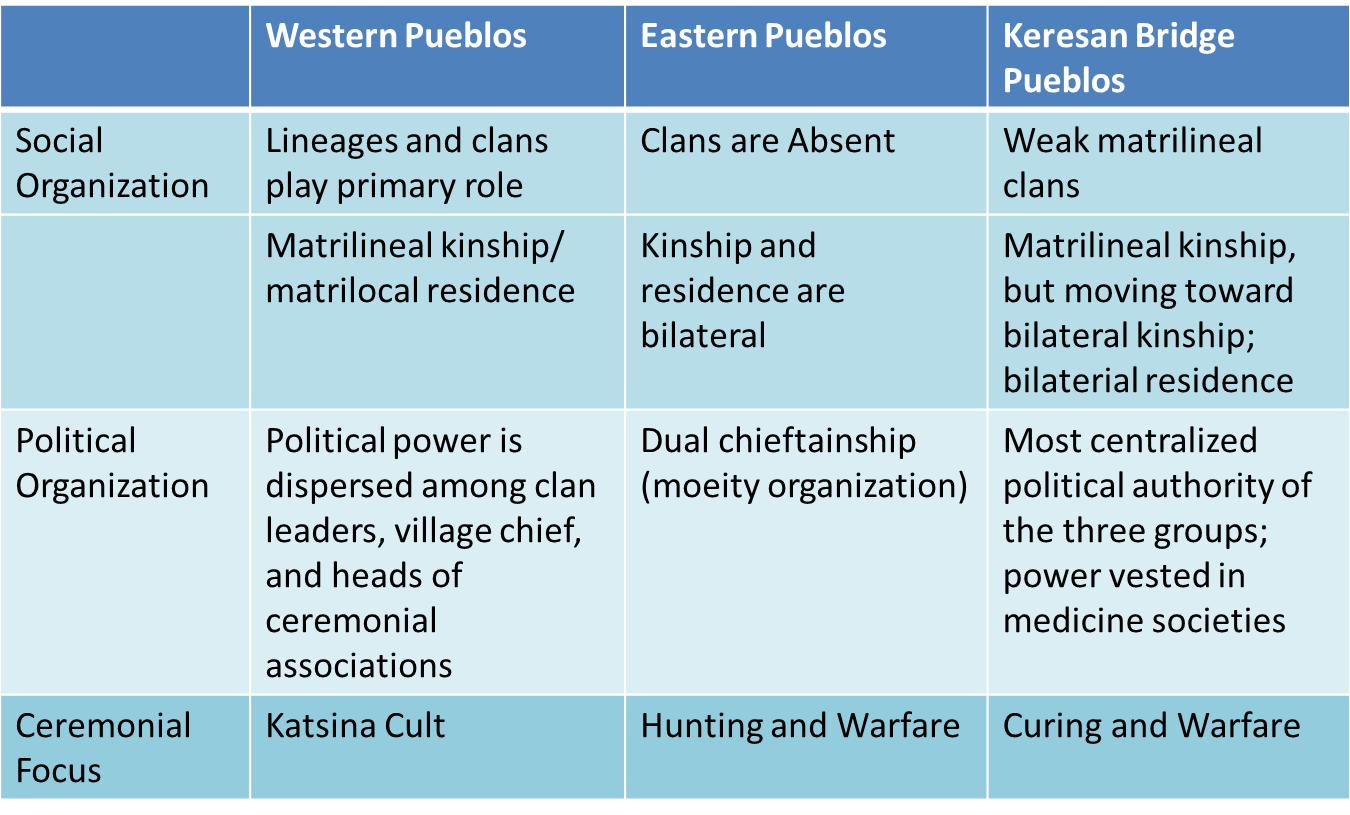

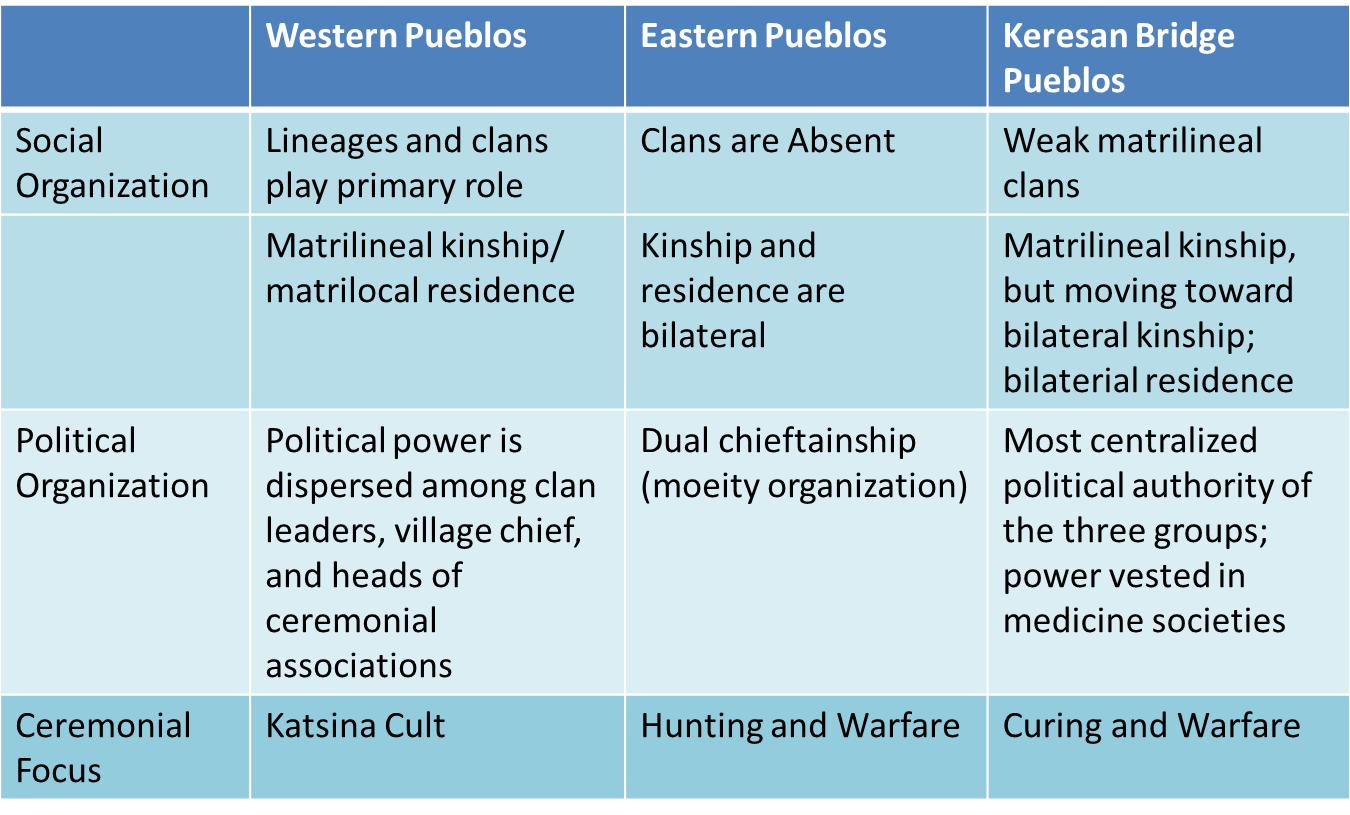

Regional Differences

The Puebloan people occupy an area characterized by a high degree of environmental diversity. This diversity, in turn—combined with the varying affects of European contact—has impacted the social practices and political organization of the villages. Although there is quite a bit of variation between the pueblos, anthropologists see three distinct patterns, which- in general- vary as one moves from the west to the east

===========================================================

|

WESTERN PUEBLOS

The western pueblos are Hopi, Hano, Laguna, Acoma and Zuni. These pueblos are located away from major watercourses, where large-scale irrigation is not possible.The subsistence economy of these pueblos is based primarily on floodwater farming (the capture of runoff after rains) and dry farming (dependent upon rainfall) techniques. Agriculture is carried out in small, family-owned or clan-owned fields, using relatively simple technology. Matrilineal clans play a primary role in socio-political organizations; it is the clan, for example, that controls access to agricultural fields and ceremonial knowledge. Political power is relatively dispersed among clan and/or lineage leaders, village chiefs, and religious leaders, though the greatest power (religious and secular) is yielded by the religious leaders. The kachina cult, focused on bringing the much-needed rains for the agricultural fields, is important.

|

|

|

_01.jpg)

|

|

View from the Hopi Mesas

Source - Shutterstock # Image ID:1730994

|

Kachina doll

Source - By Hnapel (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

|

|

EASTERN PUEBLOS

In contrast, the so-called eastern pueblos are located in the lush Rio Grande valley, where irrigation agriculture is possible. In these pueblos, clans are weak or absent and instead the townspeople are organized into larger, non-kin units called moeities. (Each town has two moeities, and each person belongs to one moiety or the other). Religious leaders are again important, but their power is limited to religious matters. Authority in secular matters resides in two secular leaders operating within a system of dual chieftainship. Under this system, each moeity is represented by a tribal chief, one of whom governs in the winter and spring and the other of whom governs in the summer and fall. Thus, among the eastern pueblos, the moiety has replaced clans as the primary unit of social organization, and it is the moiety that organizes people for communal projects and activities. Inheritance is bilateral, the kachina cult is weak or absent, and special sodalities- or social/ceremonial organizations- play an important role in the communities. The kachina cult is only weakly developed and instead their ceremonies focus on hunting and warfare.

|

|

|

Rio GrandeValley

Source - Shutterstock # Image ID:207643

|

|

|

KERESAN BRIDGE PUEBLOS

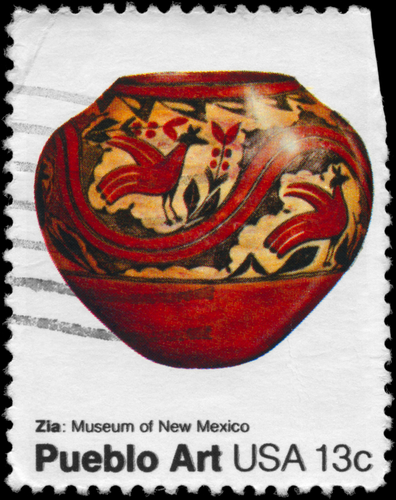

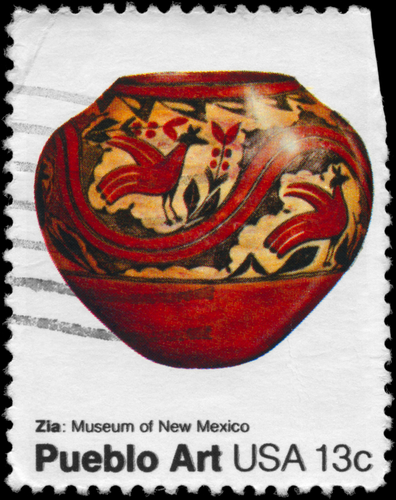

Finally, intermediate between these two differing patterns are the Keresan bridge pueblos (Zia, Santa Ana, San Felipe, Santo Domingo, and Cochiti). Among these pueblos, matrilineal clans and lineages are present, but they do not hold the power that they do in the western pueblos. Instead, power is vested in medicine societies which coordinated the needed communal tasks and who allocate land. The kachina cult is only weakly developed, and instead their ceremonies focus on curing and warfare. Kinship is matrilineal, but moving toward a system of bilaterality

|

|

Stamp showing Pottery of Zia Pueblo

Source - Shutterstock # Image ID:98381888

|

Click next page to continue.

Modern Issues Facing the Pueblo Indians

Land rights and water rights are two issues facing Pueblo Indians today. Since the arrival of the first Europeans, Pueblo Indians have struggled to retain access to the lands that their ancestors had used. Except for the Hopi (who did not receive title to their land until 1882, when the U.S. government set aside a reservation for them), most of the Pueblo villages received clear title to the lands beneath and adjacent to their villages from the Spanish government. However, in subsequent centuries, ranchers and others have often settled on, and attempted to gain title to, these lands. More recently, many Puebloan groups have fought to have other lands—outside of their original land grants but nonetheless important to them—returned. One of the most famous examples involves the case of Blue Lake, an important religious place for the people of Taos Pueblo. After a 65-year struggle, the people of Taos succeeded in having Blue Lake returned to them.

Another important issue involves water rights. Winters v United States, a 1908 case, solidified the water rights of Native Americans residing on reservations. Specifically, the courts ruled that tribes on reservations have prior rights to the waters found both on and under the grounds of the reservation. Despite this ruling, known as the Winters Doctrine, Pueblo Indians continue to struggle to maintain access to water rights.

Practice Quiz # 3

.jpg)

_01.jpg)