Source: Kobby Dagan / Shutterstock.com

The Zuni

Module 5

|

Source: Kobby Dagan / Shutterstock.com |

One of the western pueblos, the town of Zuni is located about 40 miles southwest of Gallup, New Mexico. At contact, the Zuni people lived in six separate villages spread out along a fifteen-mile stretch of the Zuni River. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, however, the Zuni people congregated into one village, where their descendants continue to live today.

Click on next page to continue.

Like all Pueblo Indians, the Zuni (who refer to themselves as Ashiwi) can trace their heritage back to at least the time of Christ. Oral histories and archaeological data suggest that the Zuni people were once spread widely throughout the Southwest, and that their ancestors began to aggregate in the Zuni region between about A.D. 1250 to 1300. The Zuni pueblo of Hawikku was the first Southwestern village to be encountered by Coronado in his legendary search for the Seven Cities of Gold. At that time, the Zuni lived in six large villages along the Zuni River; during the Pueblo Revolt, however, they fled to the top of Corn Mountain for safety.

|

|

After the Spanish Reconquest of the region in 1692 the population congregated into one village where they have remained since. Because of their closer proximity to Santa Fe, the Zuni have experienced greater European contact and influences than the Hopi. However, they experienced only sporadic contact with the Europeans until the late 1800s. After that time, anthropologists, missionaries and educators began to interact with the Zuni on a more frequent basis. |

|

Zuni Pueblo with Corn Mountain in the background Source - New Mexico Digital Collections, Fray Angelico Chavez History Library, Graphics |

|

The Zuni language is unrelated to any other known language.

Like the Hopi, the Zuni lack access to permanent irrigable rivers. However, water near Zuni is far more abundant and predictable than water in the Hopi region. Year-round water is available from the Zuni River as well as from the numerous springs and several lakes that dot the region. Soils in the Zuni river valley are deep and fertile, allowing for successful agriculture. Nonetheless, precipitation in the region is quite variable, resulting in variability in year-to-year crop yields. To offset the risk associated with this variability, the Zuni traditionally try to maintain at least a two-year supply of stored crops. Like the Hopi, the Zuni practiced a variety of agricultural techniques including small-scale irrigation, ak chin farming, and dry farming. In addition to these methods they also construct waffle gardens, which are small, but highly productive, agricultural plots built in shallow, square depressions separated by low mud walls, to make waffle-like cells. The low walls around the plots help conserve water, regulate temperature and protect plants from the wind.

Click on next page to continue.

Most of our information about the social organization of the Zuni comes from the late 19th or early 20th centuries, by which time it almost certainly had been modified from that of the pre-contact period. Changes in Zuni society likely accompanied the consolidation that occurred in 1692, as the population shifted from living in six separate villages to one. Additionally, Spanish and European policies have similarly contributed to changes in Zuni society. Traditional Zuni society was theocratic, with power vested largely in the hands of the Priestly Council. This council was responsible for selecting and installing the governor and tribal council, two institutions created by the Spaniards, as well as selecting and installing various traditional religious officials. Although once quite powerful, in the early 1900s the Council of Priests lost much of its power due to policies by the federal government (see below). Since 1934, secular power has been concentrated in a democratically elected tribal council which was created when the Zuni accepted the Indian Reorganization Act.Thus, Zuni government has shifted from a theocracy to a democracy.

|

|

Pahlowahtiwa, Governor of Zuni, 1899 Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APaliwahtiwa%2C_Governor_of_Zuni%2C_full-length%2C_seated_-_NARA_-_530901.jpg

|

Like the Hopi, the Zuni were matrilineal and matrilocal. However, the matrilocal clans had less power than they did among the Hopi, and it was the household—not the clan—that was the basic economic, social, and religious unit. At Zuni, clan function was largely limited to the regulation of marriage through clan exogamy.

Click on next page to continue.

The Zuni have perhaps the most complex ceremonial life of any of the pueblo groups; a situation that may in part have resulted from population consolidation that followed the Pueblo Reconquest. Zuni ceremonial life is controlled by various societies and organizations, including six esoteric cults, twelve medicine societies, six kiva groups, and twelve priesthoods. Like the Hopi, the Zuni have a Cult of the Katsinan, although this cult does not play as major of a role at Zuni as it does at Hopi. This cult has six groups, each with its own kiva and priests, and all boys are initiated into one of these six groups. The Koyemsi, or Mudheads, are associated with the katsina cult. These sacred clowns display a grotesque appearance and uncouth behavior, as a result of their incestuous brother-sister parentage. Mudheads are said to possess black magic, and are considered both entertaining and dangerous.

The Bow Priests are perhaps the most important of the twelve priesthoods. Traditionally, membership into the Bow Priesthood was limited to those warriors who had taken scalps (although the priesthood continues today without this requirement). The Bow Priests were responsible for protecting the Zuni people against both internal and external threats, and as such, the functioned as the executive arm of the Council of Priests. If an individual was charged with a crime, their guilt or innocence would be determined by the Council of Priests but their punishment would be meted out by the Bow Priests, since the Council of Priests were to remain "pure" of heart and removed from such matters. The Bow Priests worshipped Ahayuda, the twin war gods, and they were responsible for caring for decorating and caring for the carved wooden figures made to represent these gods.

|

|

Warshield of the Zuni Bow Priesthood, 1884 Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AZuni_bow_priesthood_Symbolic_War_Shield_EthnM.jpg

|

Witchcraft among the Zuni was a serious crime punishable by death—a punishment that would, of course, be meted about by the Bow Priests. In the early 1900s, this situation changed when the federal government cracked down on the witchcraft trials and jailed the bow priests. This resulted in a loss of power for the Council of Priests.

Click on next page to continue.

In Zuni belief, there are two categories of people: the raw people and the cooked people. Raw people are supernatural beings who are capable of taking many forms, including that of the human form. Cooked people, also known as the daylight people, are humans.

Two important supernatural beings for the Zuni are the twin boys, who are alternatively called the Beloved Twins, the Twin War Gods, or the Ayahuda. These twins, who were created in the beginning of time by Sun Father, are credited with leading the people out of the underworld to the earth. Once on earth, the people split into groups and spread out across the land. One of these groups were the Zuni, who were assisted in the many difficulties they encountered during this migration by the War Gods. Once the Zuni reached Corn Mountain their migrations stopped and they settled there. Upon death, the Zuni return to the land of the underworld via the Zuni River, which serves as a pathway connecting the dead to Katsina Village, which is located beneath the Zuni Salt Lake.

While the number four—representing the four cardinal directions-- had major ideological significance for the Hopi, among the Zuni the number six was important. For the Zuni, there are six, not four, directions; these are north, south, east, and west, as well as the zenith and nadir. This is why, for example, there are six katsina groups among the Zuni.The most important of the Zuni ceremonies is the Shalako ceremony, held near the winter solstice and following the fall harvest. Shalakos are supernatural beings (a type of katsina) that serve as couriers for the katsinas that live in the underworld Katsina Village. During the Shalako ceremony, which is held to give thanks for the fall harvest and to bring blessings and well being to the people, six costumed men impersonate the shalako beings by wearing impressive, twelve-feet tall costumes. Each of the six Shalakos parades across the river and into the town in a ceremony that lasts all night.

|

|

|

|

Shalako Ceremony, 1898 Source - https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14596359678/

|

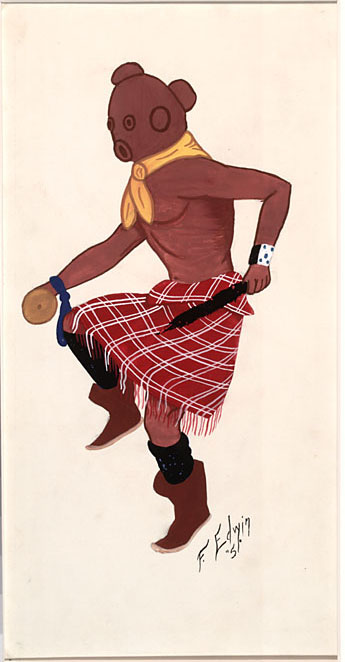

Drawing of Pautiwa (Zuni Sun God) Kachina and Hakto (Zuni Wood Carrier) Kachina, 1900. Source - http://collections.si.edu/search/direct/L3NlYXJjaC9yZXN1bHRzLmh0bT9xPTA4NTQ3MjAx

|

Click on next page to continue.

When the Zuni reservation was created in 1877, its boundaries did not include the Zuni Salt Lake, a sacred area to the Zuni people. Zuni Salt Lake is a shallow body of water that evaporates every summer, leaving behind salt deposits. In prehistoric and historic times, these salt deposits were collected and used by numerous Native American tribes. The lake is sacred to the Zuni people for many reasons: it is home to the revered Salt Mother, and it is beneath this lake that the Zunis return to live (in Katsina Village) after they die. Additionally, the salt itself is used in many Zuni ceremonies. Despite the importance of the lake to the Zuni people, it was not included in the Zuni reservation boundaries but was instead placed into federal ownership in the 1880s. Since that time, the Zuni have fought to regain custody of and protect the lake. It was returned to the Zuni in 1977, but subsequent plans to construct a coal mine nearby threatened to lower the water level in the area and destroy the lake. The Zuni once again rallied to right for the lake, and plans for the coal mine were abandoned in 2003.

|

|

Zuni Salt Lake

Source - By Bureau of Land Management, Dep't of Interior, U.S. Government - U.S. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2358320

|

Another legal battle that was successfully fought by the Zuni involved the Ahayuda, or carved Twin God figurines. These wooden figurines are carved by priests and placed in shrines on the reservation, where they are considered to be communal property of the Zuni and where they are intended to remain until they disintegrate by natural means. They are considered living, powerful deities, and their removal from the caves is dangerous. Unfortunately, however, over the years numerous of the figurines have been stolen by looters who have sold them to art collectors and museums. Under the Native Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which (among other things) requires sacred objects to be returned to the tribes, the Zuni recently have been able to recover all sixty-five of the Ahayuda figurines known to be in the possession of collectors and museums.

|

|

Shring with caved wood Ahayuda figurines, 1899

Source -http://collections.si.edu/search/direct/L3NlYXJjaC9yZXN1bHRzLmh0bT9xPTAyMzMwYTE= |

Click on next page to continue.