The O'odham

Module 6

Introduction

|

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:San_Xavier_del_Bac.jpg

|

San Xavier del Bac, Mission established by Father Kino in southern Nevada. Located on what is today the Tohono O'odham Reservation outside of Tucson, Arizona, the mission is still used for church services

|

|

Prior to contact, the O'odham (also known as the Pima and Papago) lived in scattered farmsteads spread across the Sonoran desert of southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Their first sustained interaction with the Spaniards began in 1687 when Father Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest, established a series of missions in the general region. Written accounts from that time indicate that the O'odham subsisted off both wild resources and agricultural products, with the relative contributions of these foods varying from year to year and across the landscape. The arrival of the Europeans brought substantial changes to this lifestyle, however, and today O'odham lands are confined to six reservations in southern Arizona.

|

Required Readings and Resources

- Griffin-Pierce Chapter 5

- Watch the film "Unnatural causes. Bad sugar." (Kanopy streaming video, 30 minutes)

- Video can be streamed through unlv library: http://unlv.kanopystreaming.com.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/video/unnatural-causes-bad-sugar

Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to describe the likely origins and early history of the O'odham

- Students will be able to describe how the environment affected the settlement and subsistence patterns of various O'odham groups

- Students will be able to describe the social mechanisms and adaptive strategies that were used by the O'odham to offset the risk inherent in surviving in their environment

- Students will be able to describe the effects that European impact had, and continues to have, on O'odham lifeways and health

- Students will be able to define major terms and concepts relevant to understanding the O'odham culture

Major Concepts and Terms

- Father Kino

- Sonoran desert

- Hohokam

- Piman language

- Hia-Ced O'odham

- Tohono O'odham

- Akimel O'odham

- Tinaja

- Saguaro

- Kia

- Calendar stick

- Rain Ceremony

- Naming Ceremony

- Diabetes

Additional Resources

Additional information (optional) about calendar sticks

Click on next page to continue.

Origins and Early History

|

|

We cannot be certain how long the O'odham have lived in the Sonoran desert, though the O'odham and many archaeologists believe that they are descendants of the Hohokam, a prehistoric people that lived in the area from about the time of Christ until approximately A.D. 1450. The Hohokam were farmers who cultivated crops using a combination of techniques including floodwater farming, ak chin farming, and irrigation agriculture. They are best known, however, for their large and complex irrigation systems constructed along the Salt and Gila Rivers within what is today Phoenix, Arizona. At their height these prehistoric systems contained more than 300 miles of canals, some of which were long as 12.5 miles. Accompanying this system was an elaborate social organization characterized by a political network that spanned villages, a thriving craft specialization and trade network, and complex architecture that included large, multi-story structure.

|

|

|

|

Remnants of a multi-story Hohokam structure, dated to about A.D. 1350, found at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument.

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=54612679&src=id

|

|

|

For reasons that are not fully understood this complex society begin to decline in the late 1300s, and by 1450 A.D. the Hohokam culture no longer existed. Although the region was still inhabited, the large villages and irrigation canals sat abandoned. Instead, a simpler culture existed that was characterized by smaller settlements, simpler houses, and simpler farming techniques. Archaeological evidence and oral histories from the O'odham suggest that a series of catastrophic floods combined with salinization problems may have caused the irrigation canals to fail. Whatever the case, when the Spaniards arrived it was these simpler villages that were encountered.

|

|

Hohokam bowl, dating to about 1000 A.D.

Source - Dr Karen Harry's Personal Collection

|

|

Language

|

|

Spaniard presence in the region began in 1687, when Father Kino established a series of missions in the upper Sonoran desert. Missionary reports indicate that the region was then occupied by one group of people, all of whom spoke the same language. This language, termed Piman, is part of the Uto-Aztecan language family that includes other languages such as the Hopi, Shoshone, and Commanche. Although different dialects exist within the Piman language, all are mutually intelligible.

|

Distribution of northern Uto-Aztecan languages

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ANorthern-UA-languages.png

|

Click on next page to continue.

At contact the Piman-speaking Indians lived almost entirely within the Sonoran Desert, which is located within the larger Desert Region of the Basin and Range province. The region is arid, though rainfall gradually increases as one moves from the west to the east. It has two rainy seasons, the summer and the winter. Winter rains tend to be gentle and cover a large area; summer rains, in contrast come in the form of highly localized and often torrential thunderstorms. Thus, there is a high degree of spatial variability in the areas that will receive water from the summer rains. Additionally, there is a high degree of temporal variability in these rainfall patterns, such that it is difficult to predict how much rain an area will receive in any one year. This unpredictability in rainfall made living in the region a risky endeavor.

When Father Kino's Jesuits arrived in 1687, they encountered differences in subsistence patterns that they believed reflected differences in cultural identify. They assigned the names "Pima" and "Papago" to these people, and these names have remained throughout the centuries. However, the Indians' term for themselves is "O'odham," meaning "the people," and it is this term that we will use here. The Jesuits further identified four major groups within the people they referred to as "Pima" and "Papago." These were the Sobaipuri, the Hia-Ced, the Tohono O'odham, and the Akimel O'odham. The Sobaipuri quickly became extinct, however, so most accounts deal with the remaining three groups. These groups, while all closely related, maintained slightly different lifestyles due to differences in their environmental settings.

|

|

|

|

|

The Sonoran desert is best known for its large Saguaro cacti, which are restricted to this region

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sonoran_Desert_N_of_Phoenix_AZ_40968.JPG

|

Tinaja (watering hole in bedrock)

Source - Dr Karen Harry's personal collection

|

The Hia-Ced territory. The rock circle in the foreground is a sleeping circle, which once held a temporary shelter

Source - Dr Karen Harry's personal collection

|

Hia –Ced O'odham

The Hia-Ced O'odham, also called the "no villagers" or the "sand people" by the Spaniards, lived in the driest, westernmost, area of the Piman-speaking territory (see photo of The Hia-Ced territory above). This region receives less than 5 inches of rainfall per year and even less in effective moisture, since much of the rain evaporates before it reaches the ground. The lack of rain limits the type vegetation that can grow in this area, and as a result the Hia-Ced lived in small groups that moved nearly constantly in search of food. Their diet consisted primarily of reptiles, insects and small mammals, and wild plant resources such as mesquite and palo verde beans that could be collected from localized microenvironments. For water, they relied on tinajas (depressions in rocks that filled seasonally with water; see photo of Tinaja above. Shelters were simple windbreaks laid out in so-called "sleeping circles," where the desert pavement had been cleared of rocks. The Hia-Ced, who practiced no farming, disappeared as a separate group by the late 1800s.

Tohono O'odham

To the east of the Hia-Ced lived the Tohono O'odham, also referred to as the "desert people" or "two villagers" by the Spaniards. This area is wetter than that occupied by the Hia-Ced O'odham, receiving between about 5 and 10 inches of rainfall per year. Although permanent rivers are rare, water could be obtained from springs located in the mountains and from lowland ponds filled during summer rainstorms. Plant life is more abundant in this area than in the Hia-Ced region, resulting in a greater variety and abundance of edible resources

Cholla fruit provided an important source of calcium, with just two tablespoons of fruit providing more calcium than an entire glass of milk

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-388396321/stock-photo-cholla-cactus-bearing-fruit-sedona-arizona.html?src=ezVMdaUrORH80OU0WSJsWQ-1-43

|

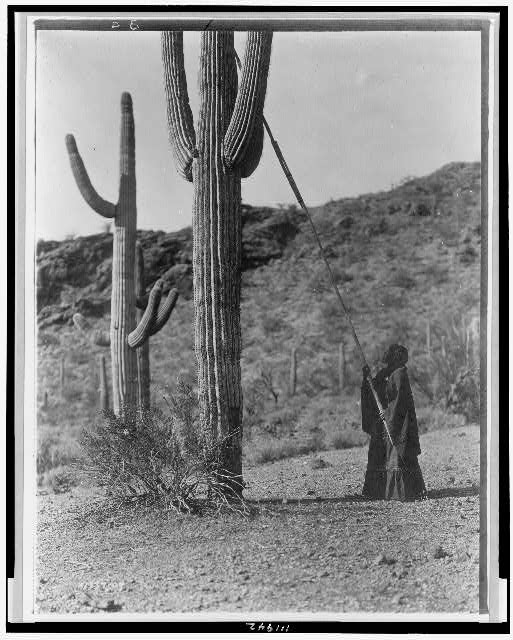

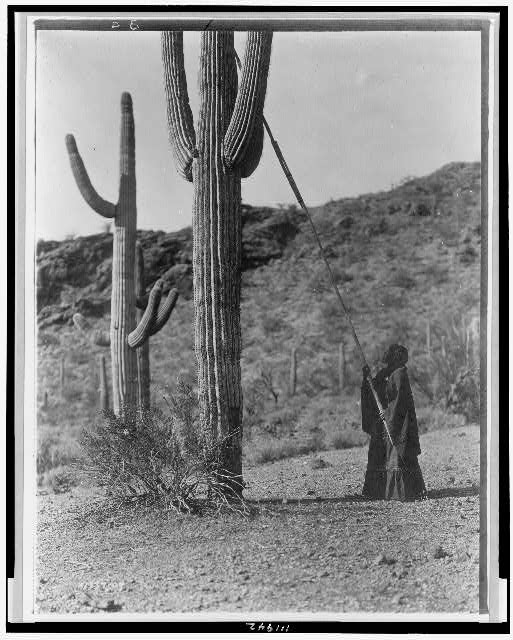

Tohono O'odham using long pole to harvest saguaro fruit, ca. 1907.

Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/94512120/

|

These resources were supplemented with agricultural foods raised using ak chin farming techniques. The Tohono O'odham thus relied on both agricultural and wild resources, and practiced a biseasonal settlement pattern to enable them to exploit both types of resources. In the summer, they lived in large summer villages located close to their agricultural fields, but when the summer ponds began to dry up they moved to smaller, winter settlements near the mountain springs.

Due to the substantial variability in summer rains agriculture for the Tohono O'odham was a risky venture. Because of this, most of their diet came from wild resources. During bad years, when most or all of their crops had failed, the Tohono O'odham might help the Akimel O'odham in their agricultural fields in exchange for a portion of the harvest. One important wild resource was the saguaro cactus, whose fruit was collected every summer.

Each Tohono O'odham family had a location in a saguaro grove where they would camp for three weeks in late June/early July when the fruit was ripening. These camps were a social event as well as an economic one, since they allowed families to get together, visit, and exchange gossip. Women would go out early every morning with a long stick to knock the ripe fruit off of the tall cacti. Once enough fruit had been collected, they would return to camp where they would spend the remainder of the morning simmering the fruit over a large fire. The resulting liquid would then be strained and the pulp either eaten, made into wine, or dried and stored for later use. The seeds would be saved and later ground into a nutritious flour.

|

Akimel O'odham

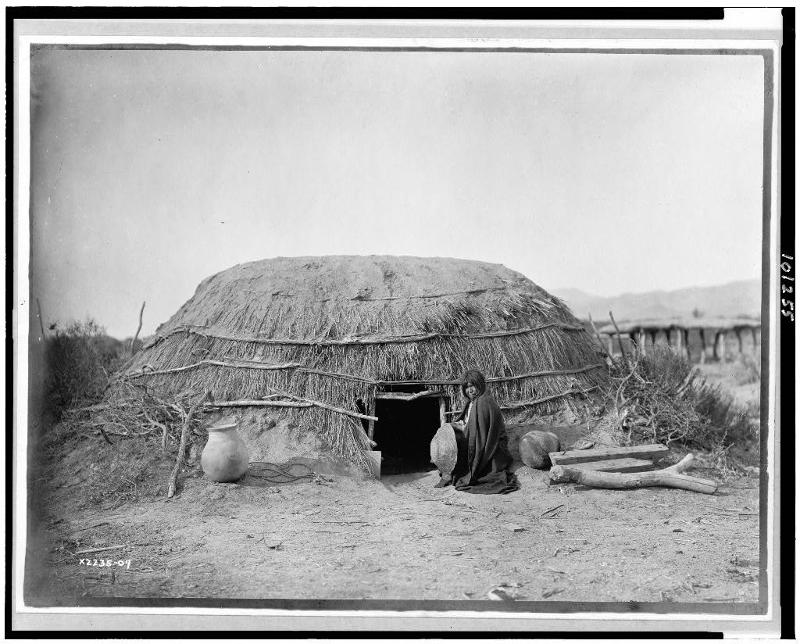

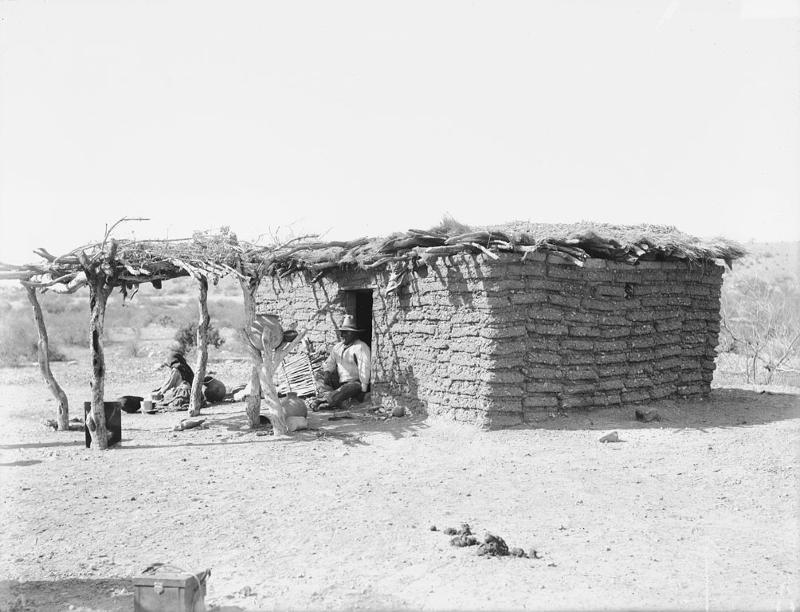

The Akimel O'odham lived to the north of the Tohono O'odham on terraces adjacent to year-round rivers such as the Gila, Salt, or Santa Cruz. They relied on crops obtained through floodwater farming supplemented by wild plants and animals collected or hunted on the alluvial floodplain. The Akimel O'odham had the largest villages of any of the O'odham groups and, because they lived by rivers and in single, year-round settlements, were called the "river people" or "one villagers" by the Spaniards. About 40% of their diet came from agricultural foods, the highest percent of any of the O'odham people. Despite their permanence, their houses were constructed of brush walls and were scattered widely from one another in a rancheria settlement pattern, lending the settlements an air of impermanence. In addition to corn, beans, and squash, the Akimel O'odham grew cotton which they used to weave into cloth, and devil's claw which they used for making baskets.

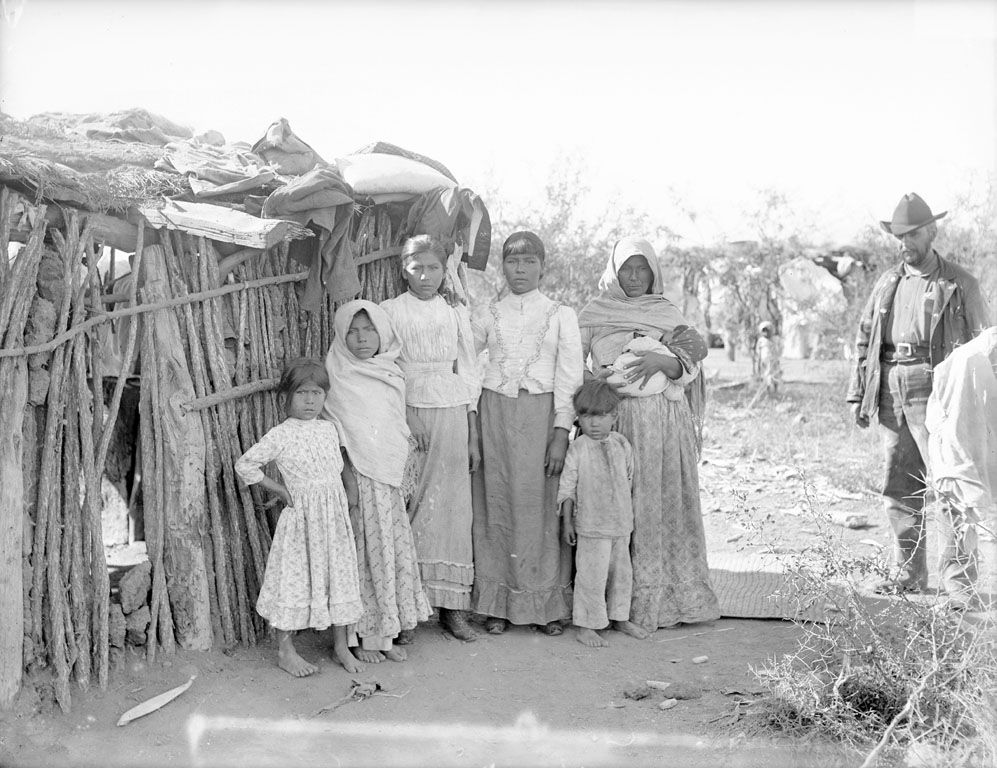

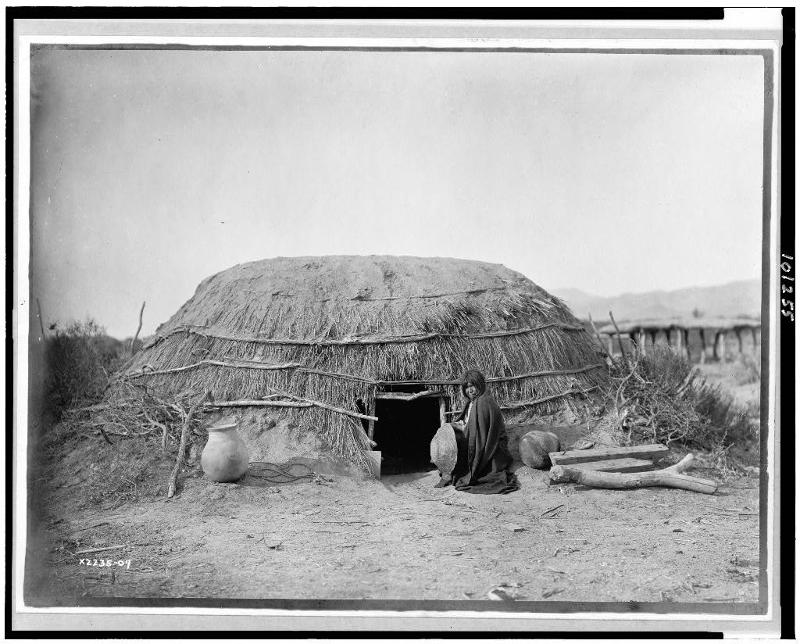

Traditional O'odham house made of brush, 1907

Source - http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/cph/3c00000/3c01000/3c01200/3c01255v.jpg

Map of O'odham Past and Modern Reservations

Instructions: Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between O'odham Past Territories and O'odham Modern Reservations pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

Click on next page to continue.

Adaptive Strategies

Because of the high risk environment in which they lived, the O'odham developed a variety of risk minimizing strategies to help them survive. These strategies included both diversification and flexibility and an ideology that supported food exchange. Diversification is reflected by the great variety of resources that contributed to their diet; flexibility is reflected by the willingness to modify their subsistence strategies as needed. For example, in most years mesquite beans merely supplemented the Tohono O'odham diet, but in years of crop failure, this resource provided important emergency rations.

The O'odham were expected to redistribute food to those in need, and several customs helped to ensure that this occurred. In dry years, the Akimel O'odham (who had a more secure agricultural base) were expected to hire less fortunate Tohono and Hia-Ced O'odham to help work their fields. In return, the fieldworkers were allowed to take whatever food they needed. Similarly, within a single village, successful hunters were expected to share their meat with others in need. These mechanisms helped to even out the spatial and temporal variability that existed in food availability, and to ensure that no one starved in lean years.

Mesquite beans could be eaten fresh or dried and ground into flour for later consumption

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-1531393/stock-photo-cluster-of-mesquite-pods-or-prosopis-fabaceae-legumes.html?src=agGDInl0QxH5XScdPVPKqA-1-9

Click on next page to continue.

Material Culture

|

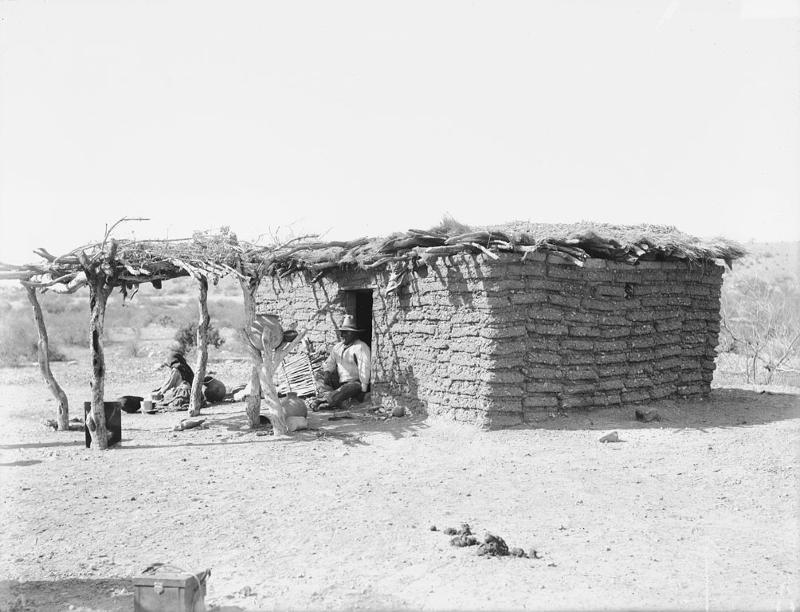

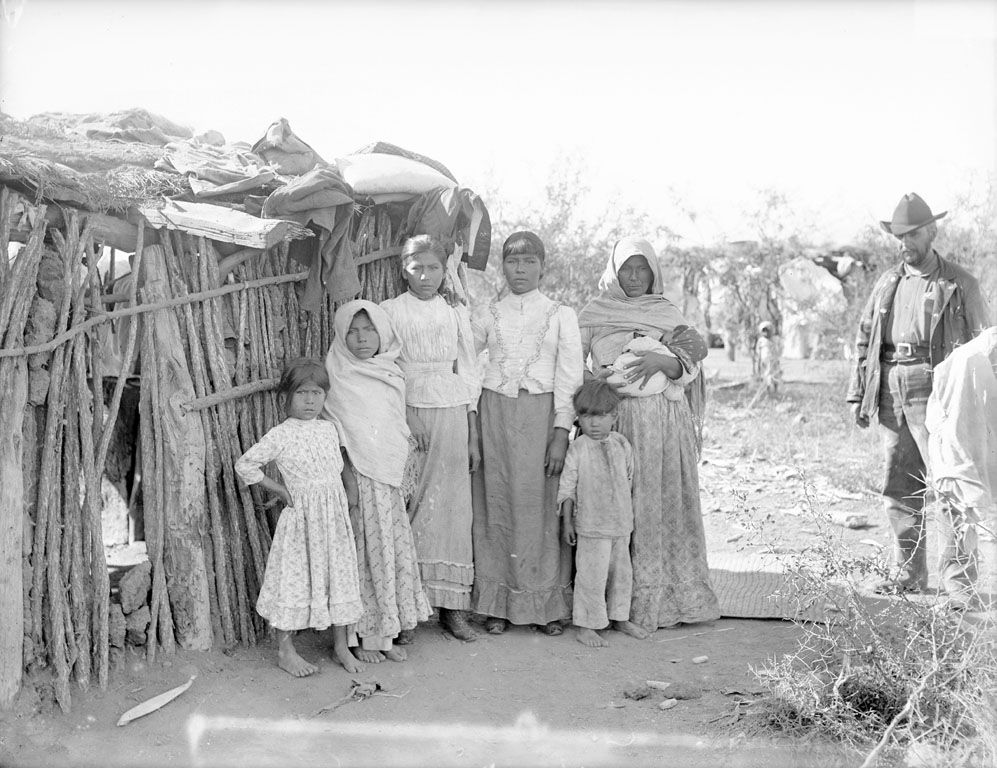

Adobe brick house with sunshade, 1894

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02785c.jpg

|

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, O'odham houses were constructed with brush walls and a dry earthen roof. Settlements generally consisted of three to four of these houses, one of which would be occupied by a married couple and the others by the families of their married sons.

|

|

The kia was a cone-shaped carrying frame used by women.This frame was made by fastening a net made of yucca fiber cords to a framework of four poles. It was designed so that it could rest upright on its own while women were loading it and then be placed on women's back for transportation.

|

O'odham with kia, 1894

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02747b.jpg

|

|

.jpg)

O'odham cooking shelter, 1894

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02770d.jpg

|

These extended family groups would share other facilities, including a brush-enclosed kitchen, storage facilities, and small huts where menstruating women would stay. Adobe style houses were not used by the O'odham until after the arrival of the Spanish (although they had been constructed by the prehistoric Hohokam).

|

|

Calendar sticks were cactus ribs that had been marked with a series of lines, dots, and notches to mark events that had happened in the past. These markings served as mnemonic devices to remind men of important happenings in their history. The oldest sticks in existence go back to 1833, and ethnographic accounts indicate that with the help of the calendar sticks O'odham men could recite the history of their village for 80 or more years.

|

Calendar Stick

Source - http://www.nmai.si.edu/exhibitions/infinityofnations/southwest/104878.html)

|

Click on next page to continue.

Social and Political Organization

|

Ceremonial Life

|

|

The patrilineal extended family was the basic social unit of the O'odham.

Settlements were mostly patrilocal, although flexibility existed. Above the family level were patrilineal clans organized into moieties.

Within the village, there was minimal political structure. Each group had a headman who received nominal respect and power, though he lacked the ability to compel others. Rather, his job was to open discussions and to cajole others into agreement. No wealth differentials existed between the the headman and others.Most groups also had at least one shaman who provided spells and who called upon his spirit helpers to cure illnesses.

|

The O'odham followed a ceremonial calendar with established annual rites. The most important of these was the Rain Ceremony, which marked the beginning of their new year. The hallmark of the Rain Ceremony, which took place in summer after the saguaro fruit had been collected, was the drinking of fermented saguaro wine. In this ceremony the people filled their bodies with the saguaro liquid to signify their hope that the rains would come and similarly fill the earth. Soon after the completion of the Rain Ceremony the crops were planted.

The Naming Ceremony was another important rite, though it was not necessarily an annual event. The purpose of the Naming Ceremony was to redistribute food from a village that had plenty to one that was suffering from scarcity. The decision to perform this ceremony was made by the villagers who were experiencing the food shortage. The suffering villagers would visit a settlement that had experienced a bountiful harvest, and sing a song that incorporated the names of the men in that settlement. As a man's name was called, his wife or daughter would jump up and run, only to be chased by the visitors. Once caught, the woman would lead her "captors" to her husband or father, who would "ransom" her by giving foodstuffs to her captors.This enabled villagers who had experienced a poor harvest to obtain food, but etiquette required that they repay the later that season or the following year.

|

|

Tohono O'odham family near their home, 1894

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_027870d.jpg

|

Evening Light on Signal Hill Petroglyph

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-130357172/stock-photo-evening-light-on-signal-hill-petroglyph.html?src=szBKAsGQP4JezISCYfT9ZQ-1-4

|

Click on next page to continue.

Impact of European Contact

The arrival of the Spaniards ushered in profound changes for the O'odham. When Father Kino arrived in the late 17th century, the Apache were already pressing hard on the eastern limits of the O'odham territory. With the introduction of horses, Apache raids intensified and resulted in the elimination of the Sobaipuri people. For defensive purposes, the remaining O'odham soon abandoned their rancheria settlements and congregated into larger, more closely spaced, settlements. The increased Apache warfare also limited the distances that the O'odham people could travel safely, which curtailed their hunting and gathering activities.These changes in mobility and settlement patterns resulted in a greater dependency on agricultural products and a more formal political structure.

The introduction of wheat by the Spaniards further changed their lifeways. Because wheat is frost-resistant, it could be planted in the fall and harvested in the early spring before the planting of native crops. Thus, wheat essentially doubled their agricultural production and provided an important food source at a time of the year when stored foods were becoming exhausted. Finally, since wheat was more highly desired by the Spaniards than maize, it could be easily marketed. As the demand for wheat increased, more land was brought into cultivation and farming techniques increasingly shifted to irrigation, rather than floodwater, methods.

The O'odham were able to live relatively prosperous lives for several centuries. However, in the mid-19th century a drought hit. This, combined with dropping groundwater levels caused by the influx of Anglo settlers, made farming difficult. With the construction of dams upstream in the late 19th and early 20th century, the consequences were to become catastrophic. Rivers that were once irrigable became dry or deeply incised, and farming became nearly impossible. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of O'odham starved to death and those that did survive were able to do so only by accepting food rations from the United States government.The consequences from this dark period in O'odham history continue to impact the people's health today.

O'odham woman winnowing wheat, ca. 1907

Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00649911

Click on next page to continue.

Modern Issues

Perhaps the most pressing issue facing the O'odham today is diabetes, a legacy from the early 20th century period of starvation. About half of the O'odham over the age of 35 have this disease; this rate is the highest in the world and more than fifteen times that of the national average. Researchers agree that the high prevalence of diabetes is a result of the changes forced upon the O'odham early in the last century. Unable to support themselves though farming and the gathering of wild resources as they once had, the O'odham became severely undernourished. For survival, they turned to the processed foods handed out by the government. While providing the necessary calories to keep them alive, however, these foods unfortunately also led to health problems. Researchers agree that it is reliance on these processed foods, which continues in the community today, that has contributed to the high rate of diabetes among the O'odham. Today there is a movement to re-introduce native foods into the O'odham diet; current research reveals that these desert foods have important properties that allow them to naturally combat the development of diabetes.

|

Native desert plant foods such as amaranth, shown here, have natural properties that help combat the development of diabetes.

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=40291345&src=id

|

Grinded amaranth grain

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=56777683&src=id

|

Watch the video - "Unnatural causes. Bad sugar."

If you are having trouble viewing the video, click on the link - http://unlv.kanopystreaming.com.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/video/unnatural-causes-bad-sugar

Practice Quiz # 6

.jpg)