The Yaqui

Module 7

The Yaqui speak a dialect of Cahita, which is a member of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Their homeland is in Sonora, Mexico, along the lower banks of the Rio Yaqui River, an area where many Yaqui still live. Others, however, live in small communities in Arizona, having immigrated there at the turn of the 20th century to escape enslavement by the Mexican government. Theirs is a rich culture that results from a unique fusion of their Catholic and indigenous heritages.

Instructions: Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between Yaqui Past Territories and Yaqui Modern Reservations pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

Griffin-Pierce Chapter Ch. 6

The following resources are optional for your exploration but highly encouraged.

Yaqui and Mayo Easter ceremonies

Video of Yaqui deer dancer

If you are having trouble viewing the video, click on the link.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CK0aLVUqx0&feature=related

Videos of Fariseos

If you are having trouble viewing these videos, the links are below.

Understand how indigenous beliefs and practices became fused with European ones to create modern-day Yaqui society and religious beliefs

Click on next page to continue.

Early European records indicate that, prior to contact, the Yaqui lived in 80 rancheria-style settlements scattered along the lower 60 miles of the fertile Yaqui River Valley. Although this territory falls within the Sonoran desert region, the area adjacent to the river is quite lush and can be dependably farmed.

In addition to floodwater and irrigation agriculture, the Yaqui hunted, gathered wild resources, and collected shellfish and large saltwater fish from the coast. Their settlements, which consisted of clusters of dome-shaped, cane-covered houses, held an average of 250 people. Agricultural surpluses made a sedentary lifestyle possible, though Yaqui settlements were frequently moved due to flooding.

Yaqui River

Source - by Tomas Castelazo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons; http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yaqui_River.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

|

Detail of a late 17thcentury Jesuit Mission Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=74095567&src=id

|

By the early 1600s, Jesuit missionaries had begun to penetrate northwestern Mexico. Unlike the Franciscans of the northern Rio Grande region, the Jesuits working in northwestern Mexico never imposed the hated repartimiento and encomienda systems and never banned the practice of indigenous rituals. As a result, they were generally favorably regarded by the native people. Impressed after observing Jesuits in neighboring lands, in 1617 the Yaqui invited missionaries into their territory. The Yaqui proved to be eager converts and within a few years virtually all Yaqui had been converted. In adopting Catholicism, however, they reworked its beliefs and rituals to incorporate their native ones and in the process created essentially a new, syncretic religion.

The Jesuit missionaries were to have a profound influence on Yaqui lifeways. Soon after their arrival the missionaries consolidated the eighty Yaqui settlements into eight densely populated towns, each of which held between 2000 and 4000 people. The focus of each town was an adobe-walled church set within a central town plaza; surrounding the plaza were the habitation buildings. A more formalized government system, closely linked with the church, accompanied this increase in population.

The Jesuits also introduced new crops (such as wheat and peaches), work animals (including sheep, cattle and horses), and more intensive agricultural techniques. These innovations made the Yaqui valley one of the most productive areas of the entire province and garnered the attention of Spanish settlers. Spaniards began to flood into the region, with their numbers further increasing when silver was discovered in Yaqui territory in 1684. By the late 1600's hostilities had erupted between the Yaqui and Spaniards. In 1740 the Yaqui successfully revolted and drove out all Spaniards except the Jesuit missionaries. (The Jesuits, however, were soon also expelled—though not by the Yaqui. In 1767, they were withdrawn from the New World by order of the Spanish Crown). |

Click on next page to continue.

The 1740 revolt ushered in a 150-year period of relative freedom for the Yaqui people. In the absence of missionaries, they continued to practice Catholicism but also continued to re-work the religion to incorporate their native beliefs. Although periodic efforts were made by the Spanish and (after 1821) Mexican governments to tax and work the Yaqui, the Yaqui were able to resist these efforts until General Porfirio Diaz's rise to power in 1887.

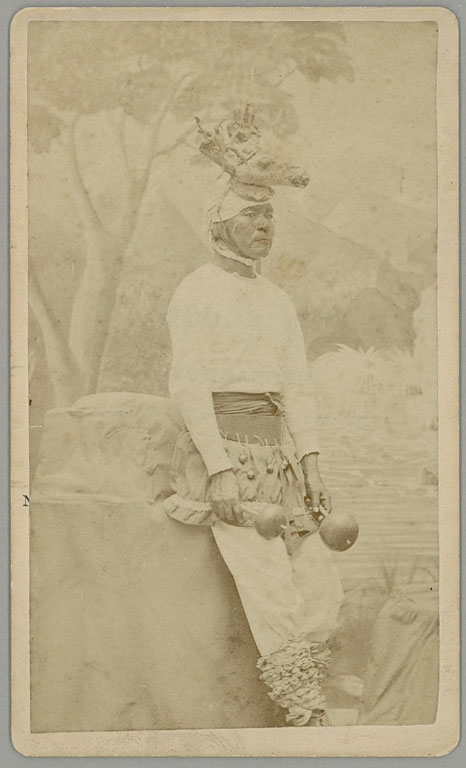

The Yaqui incorporated native rituals, such as the deer dance, into Catholic rituals during this period

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/mexico/00807700.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

|

President Diaz Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Young_Porfirio_Diaz.jpg General Diaz, considered to be a dictator by many, became President of Mexico after defeating incumbent government forces. In order to gain control of the fertile lands in Yaqui territory, Diaz initiated a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing. A bounty was placed on the heads of Yaqui warriors, and all others that did not manage to hide or escape were deported. After enduring long, forced marches they were sent to concentrations camps and sold as slaves to plantations and mines located in distant areas of Mexico. By the turn of the century, nearly all the Yaqui towns were deserted. To avoid capture and deportation, many Yaqui went into hiding and thousands of others made the long 400 mile walk northward to seek asylum in the United States. By the end of Diaz's regime, the Yaqui population had been reduced from some 20,000 people to less than 3,000. Yaqui slavery was ended in 1911 by the Mexican Revolution, but this revolution also ended with the loss of their lands. They would not regain their lands until 1939, when the Mexican government set aside a small portion of their original territory for their use. Most of the Yaquis that had fled to Arizona elected to stay there. Today, some 6,000 descendants of these immigrants live in southern Arizona in neighborhoods within or near the cities of Phoenix, Tucson, and Yuma. In 1978, the United States government officially granted them tribal recognition status and awarded them a small reservation within the city boundaries of Tucson. Most of the American Yaqui live in one of six communities, or barrios, within urban settings. These barrios retain the church-centered layout and ideology that crystallized during the Mission Period more than two centuries ago, and their inhabitants continue to follow the syncretic Catholic and native religion established during that time. |

Click on next page to continue.

The Yaqui have a complex culture that reflects the amalgamation of indigenous and Catholic traditions. Their kinship is reckoned bilaterally, but there are no post-marital residence patterns. Today, an important component of the kinship system is the concept of campadrazgo. Compadrazgo are fictive kin or godparents that play important ritual roles in a child's life. An individual might have a dozen or more pairs of godparents, each of which is obligated to help sponsor specific ceremonies in the child's life. The compadrazgo system is believed to represent a melding of the pre-European practice of ritual sponsorships and the Catholic tradition of the godparent system.

In Yaqui culture, compadrazgo help sponsor religious and other ceremonies for their godchildren

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FirstCommunionDressDoc.JPG

Click on next page to continue.

The town, or barrio, is the largest political entity in Yaqui society. As with other aspects of their culture, town government represents fusion of European and aboriginal concepts. In the eight Yaqui towns established during the Mission period, the town was the fundamental unit of Yaqui life. Each town was governed by five groups: the church, the governors, the military, the keeper of traditions, and the fiesta makers. All five entities had different functions, yet they worked in concert with one another and were considered equal in authority. (Each of these five groups still exist in the Mexican Yaqui towns, but in the Arizona barrios, only the church and the keeper of traditions have been retained). Town government reflected the Yaqui ideal of cooperation and shared responsibility rather than individual power. General meetings of all of five groups were called when necessary to make decisions affecting the whole town or to decide disputes. In such cases, everyone was free to speak and a decision was reached only when there was consensus. If there was dissent, a decision was postponed or never reached. No overall tribal organization existed except during times of military conflict.

The town, or barrio, is the largest political entity in Yaqui society. As with other aspects of their culture, town government represents fusion of European and aboriginal concepts. In the eight Yaqui towns established during the Mission period, the town was the fundamental unit of Yaqui life. Each town was governed by five groups: the church, the governors, the military, the keeper of traditions, and the fiesta makers. All five entities had different functions, yet they worked in concert with one another and were considered equal in authority. (Each of these five groups still exist in the Mexican Yaqui towns, but in the Arizona barrios, only the church and the keeper of traditions have been retained). Town government reflected the Yaqui ideal of cooperation and shared responsibility rather than individual power. General meetings of all of five groups were called when necessary to make decisions affecting the whole town or to decide disputes. In such cases, everyone was free to speak and a decision was reached only when there was consensus. If there was dissent, a decision was postponed or never reached. No overall tribal organization existed except during times of military conflict.

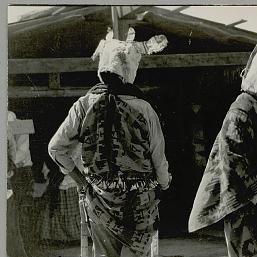

Outside the political realm, religious brotherhoods played an important social role in the communities. These brotherhoods, termed cofradias, were organizations of laymen dedicated to the service of a Christian saint or other supernatural being. Although the concept of cofradia was introduced to the Yaqui by the Jesuit priests, after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 the concept became fused with their indigenous concepts of ceremonial sodalities. One important sodality is that of the Fariseos, who represent the Pharisees or Judases who persecuted Christ. The Fariseos play an important role in the annual Easter re-enactment. Additionally, members of this sodality function much like that of the Pueblo clowns, acting with complete license and mocking every sacred institution and the social order.

Fariseos during the Easter re-enactment

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/mexico/00809200.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

|

The indigenous beliefs of the Yaqui are not well described in early Spanish accounts. However, the little information that does exist describes a belief system that could easily be adapted to the newly introduced Christian ideas. For example, pre-contact Yaqui rituals and beliefs appear to have focused largely around the notion of curing; a notion that easily fit in with Christ's role as curer. Similarly, they revered a benevolent power referred to as "Our Mother" who was associated with flowers and trees and the earth; this entity became re-worked and fused with the concept of Virgin Mary.

|

One belief not adopted from Christianity is the Yaqui conception of the supernatural landscape. The Yaqui believe that there are several worlds, which can be known to humans only through dreams and visions. The Enchanted World is the most ancient of the worlds, and is inhabited by the ancestors of the Yaqui. With the adoption of Christianity, this world became identified with the concept of heaven. A second important world is the Flower World, which symbolizes everything that is good in the wilderness world. This is the spiritual domain of the deer, and in ceremonies Yaqui Deer Dancers mimic the movements of deer in order to connect us with that world.

|

|

Virgin Mary Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gross_St_Martin_-_Grablegungsgruppe_-_Maria_(virgin_mary).jpg |

Yaqui deer dancers Sources - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Danza_del_venado.jpg and caption |

Watch this video on Yaqui deer dancers

Flowers, in turn, are important symbols in Yaqui life. They combine the ancient belief that the deer dancer is from a flower-filled spiritual world with the more recent belief that Christ's grace is symbolized by flowers that grew from the blood that he shed during the crucifixion. Flowers are thus an important weapon against evil.

Click on next page to continue.

.jpg)

Yaqui Easter Procession, ca. 1950

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/mexico/00809500.jpg and caption it

Easter is the culmination of the Yaqui ceremonial year, and the Passion Play performed at that time is the most important and elaborate of their ceremonies. This play re-enacts Christ's last days on earth, and dramatizes the triumph of good over evil.The ceremony begins the first Friday of Lent and continues every Fiday until Palm Sunday. It begins with a procession of religious leaders who are followed and taunted by Chapayekas, masked actors who are part of the Fariseo sodality.

Watch the video on Fariseos

The Chapayekas, who are searching for Christ, are initially few in number but increase in size over time, with the escalation in their number representing the accumulation of evil. While enacting these roles, the men playing the part of the Chapayekas are vulnerable to evil forces; to protect themselves they hold rosaries in their mouths under their masks. On Palm Sunday, deer dancers and members of other cofradias lead a procession bearing the image of Christ into the town plaza to represent Jesus' entry into Jerusulum. The Fariseos then chase Christ, eventually catching and crucifying him. After Christ is crucified the Chapeyekas dance jubilantly, but when they realize that Christ has been resurrected they return to do battle. During the battle they are pelted with flowers and finally defeated. Immediately after this enactment, which marks the end of the Passion Play, their godparents rush the Chapayeka actors to the church to be re-baptized. That night through the next morning the Deer Dancers perform.

Click on next page to continue.

A second important ceremony is the four day pahko ceremony, which celebrates the supernatural patron of each town. Most pahko ceremonies take place from May to early July, with different towns hosting their ceremony on different dates. These ceremonies, based on the War of the Moors and Christians, are directed by the fiesta makers who are responsible for organizing the event and assembling the large amounts of food necessary. The fiesta makers are divided into two groups, one representing the Moors and the other the Christians. Each group hosts separate fiestas in which they compete for superiority. The ritual opposition culminates in a mock battle over a symbolic castle, with the Christians winning.

Pahko Ceremony

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/mexico/00809100.jpg

Practice Quiz # 7