The River Yuman

Module 8

Historically, the River Yuman tribes lived in agriculturally-based rancheria settlements scattered along the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers.These groups include the ancestors of the modern-day Mojave, Quechan, Cocopa, and Maricopa as well as the now-extinct Halchidhoma. In addition to these Yuman-speaking groups, the Numic-speaking Chemehuevi-- who moved into Yuman territory in the 19th century-- will also be considered in this section.

The Yuman language subfamily includes four branches, of which two were spoken by the River Yuman. These are the River branch, spoken by the Mojave, Quechan, Maricopa, and Halchidhoma; and the Delta branch, spoken by the Cocopa. The other two branches include the Pai branch (spoken by the Upland Yumans; see Module 9) and the Kiliwa branch, spoken by tribes in Baja California. The Chemehuevi, who have descended from Paiutes, speak southern Numic.

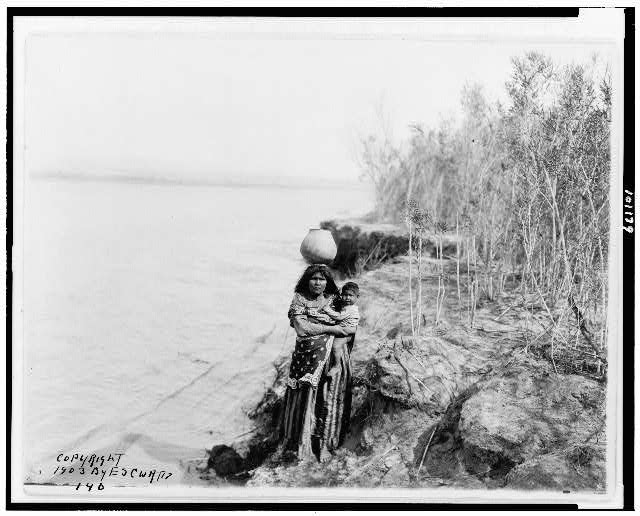

Mohave woman carrying water on her head and holding child, 1907

Source - http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/cph/3c00000/3c01000/3c01100/3c01179r.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

The map shows locations of the River Yuman Territories (a) Mojave, (b) Quechan, (c) Maricopa, (d) Halchidhoma, and (e) Cocopa and River Yuman Territories (a) Fort Mojave Reservation, (b) Colorado River Indian Reservation, and (c) Gila River Reservation.

Instructions: Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between River Yuman Territories and River Yuman Reservtions pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

Information on the Ward Valley Nuclear Waste Dump Site

Click on next page to continue.

The prehistoric ancestors of the River Yuman are known as the Patayan, a poorly defined archaeological culture found in the lowland region along the Colorado River and in the adjacent upland regions of northwestern Arizona. Like the Yumans, the Patayan people made buff-colored pottery and practiced floodwater farming. Little is known about this culture, however, because the flooding and re-working of the Colorado River channel has largely obliterated their archaeological sites. What little we do know of this culture comes from sites away from the river, in the California deserts. There, we find trails littered with broken pieces of Patayan pottery and intaglios etched in the desert pavement. These intaglios (large images made in the desert surface) were made by removing the dark colored rocks to expose the lighter desert surface that lay beneath.

"Intaglio near Blythe, California of a human figure measuring 171 feet long.

Source - Dr Harry's personal collection

Click on next page to continue.

Prior to the arrival of the Europeans there are estimated to have been between 10,000 and 20,000 River Yumans living in the lowland area. Long before the first Europeans ever stepped foot in their territory, however, their diseases—for which the tribes had no natural immunity- had already swept through the area. When the first Spaniard finally visited the area in 1776, he estimated the remaining population to be about 3000. Other than the rather substantial devastation caused by diseases, the River Yumans were largely unimpacted by Anglo contact until the mid-1800s. No missions or Spanish settlements were ever established in Mojave territory. The River Yumans were one of the few groups to have a true tribal consciousness. Tribes formed alliances with one another and appeared to be nearly constantly at warfare with members not in their alliance. There existed two opposing military alliances: the Quechan league, composed of the Mojave, Yavapai, Chemehuevi, Hia C-ed O'odham, and the western Tohono O'odham; and the Maricopa league, composed of the Cocopah, Halchidhoma, Hualapai, Havasupai, Akimel O'odham, and eastern Tohono O'odham. In the late 1820's the Quechan league ousted the Halchidhoma from the Colorado River valley and allowed the Chemehuevi to move into their abandoned territory. In 1858 the Mojave were defeated by the U.S. Army, and in 1862 the Colorado River Indian Reservation was established to the south of their traditional territory. Although this reservation was initially intended for the Mojave, only a fraction of the tribal members agreed to leave their homeland and relocate there. In addition to the Mojave that did resettle there, the Chemehuevi were placed on this reservation and later- after World War II—the federal government relocated some impoverished Hopi and Navajo families there as well. Today, this reservation is thus home to Mojave, Chemehuevi, Hopi and Navajo people, all of whom retain ties to their various heritages but collectively refer to themselves as "the Colorado River Indian Tribes" (or CRIT). The other reservations are the Fort Mojave Reservation (established in 1880 for the Mojave who had refused to leave their homeland) and the Gila River Reservation (shared by both Pima and Maricopa).

Instruction: Click on the thumbnail to see a zoomed picture of Fort Yuma.

By the 1850s, more and more Anglo settlers began to pass through Yuman territory and tensions grew between the Anglos and Indians.

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8009323

Click on next page to continue.

The lower Colorado River flows through the extremely arid Mojave Desert. Summers in the region can reach temperatures over 200° and precipitation averages less than 3" per year. The Colorado River, however, does not rely on local precipitation but is fed by snowmelt drained from mountains within a watershed some ¼ million acres in size. The river was thus a dependable source of water and, until its waters were impounded by dams in the early 20th century, regularly overflowed its banks every spring. Floods from these slow-moving waters would deposit rich silts over floodplains for distances as far as 1-2 miles from the river bank. When the water receded in June, the Yumans would plant their crops in the fertile, moist soils. Because the soils were renewed every year, crops did not need to be rotated and no fertilizing of the fields was required. For the River Yumans, farming was easy and productive. Cultivated foods comprised about half of their diet, with the other half coming from wild plants collected from the floodplain and fish taken with nets or weirs from the river.

Yuman cornfield after harvesting, ca. 1900 A.D

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02842.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

|

Like the O'odham and the Yaqui, in pre-contact times the River Yumans had a rancheria settlement pattern. Houses of a single settlement might be spread out from one another by distances of as great as 1-2 miles, with the next nearest settlement some 4-5 miles away. Houses, which were placed on low rises above the floodplain, were low, rectangular structures constructed by covering an arroweed frame with a thick layer of sand and earth. Because of the heat, however, for most of the year the people slept under a ramada with their food stored in large baskets on its roof.

|

|

|

River Yuman Indian House, 1900. Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02833a.jpg |

|

Click on next page to continue.

Dress and Appearance |

|

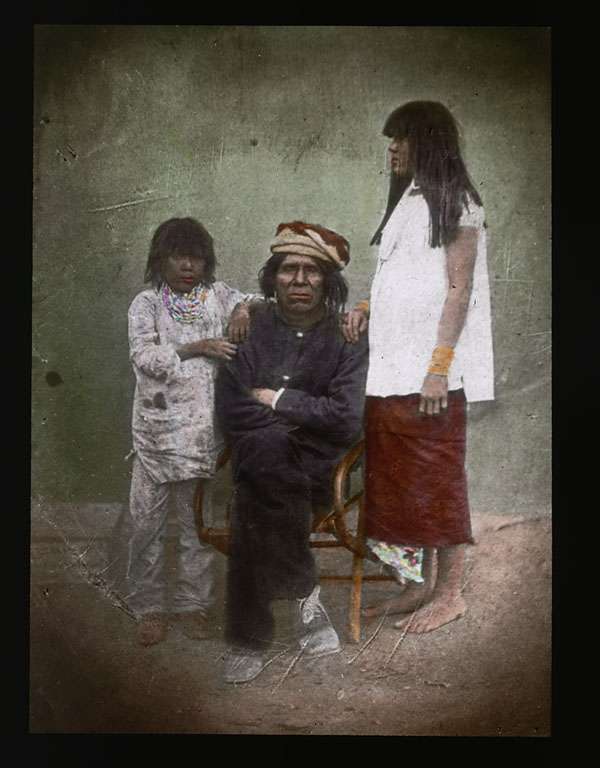

Mohave woman exhibiting face tattooing

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/southwest/02259300.jpg |

|

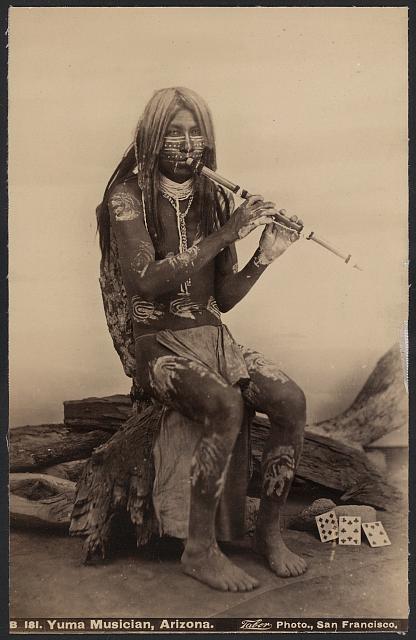

Both men and women tattooed their chins and painted their faces in elaborate designs,and men often pierced their nasal septums and ears in order to wear shell or bone ornaments. Women's hair was worn loose over their shoulders, but the men-- who took great pride in their hair—rolled it into long, rope-like strands. These "dreadlocks" might be treated with mesquite sap and plastered with reddish mud to enhance their appearance.

|

|

Mohave man exhibiting long rolled hair |

|

For clothing, the men wore breechcloths woven from the inner bark of willow and women were skirts of willow bark.

|

|

Woman wearing willow bark skirt. Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02812a.jpg |

Click on next page to continue.

Our knowledge of the social and political organization of the River Yuman tribes comes from the early historic period, when their numbers had already been largely reduced by diseases. How this reduction in population might have impacted their sociopolitical structures is unknown. The following accounts come primarily from Mojave tribe, the group for which the ethnographic record is most complete.

Unlike the other groups we have studied, the Mojave had a true tribal consciousness and considered themselves to be one people living in a single nation. They glorified in their shared identity and considered people outside the tribe to be inferior and dangerous. A tribal chief headed the tribe, though it is unclear whether this position existed prior to contact. Like other leaders in Mojave society this head chief received his position and power through dreams. However, unlike other leadership positions, the role of chief was also said to be inherited through the male line. Because the notion of inherited leadership is otherwise at odds with Mojave ideology, many anthropologists believe this was a post-contact development. Though the chief was expected to look after the welfare of the tribe he had little actual authority.

Beneath the level of the tribe the people were organized into a loose division of bands and local groups. Each band had one or more subchiefs, who obtained their positions through dreams validated by a group of elders. Whether or not these dreams would be validated depending largely on the man's personal competence and qualifications, and the power of a leader's dreams had to be continually authenticated by his success in handling various matters. Beneath the bands were the individual rancheria settlements, also loosely headed by leaders who had received their positions in dreams. Like the tribe's head chief, these leaders had little real authority; according to Mojave norms, important matters were decided by consensus. Marked differences in wealth did not exist.

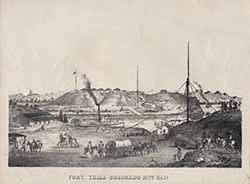

Chief Juan Chivaria, Maricopa subchief, with wife and daughter, ca. 1871

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/73/06706200.jpg with the caption.

Click on next page to continue.

The world was brought into being when Sky and Earth gave birth to a child, Matavilya, who built the sacred Great Dark House where Mojave dreamers would later come to receive their power. After offending his daughter, Matavilya was killed and cremated and the Great Dark House was burned. Leadership then was assumed by the diety Mastamhό, who proceeded to bring shape to the land. He also created the Colorado River and the people, who he separated into different clans and tribes, and created the sacred mountain Avikame (commonly known as Spirit Mountain) where all future unborn souls lived. It was at there at Spirit Mountain that Mastamhό assigned special powers and talents to those souls destined to have leadership roles in Mojave society.

Spirit Mountain, as viewed from Bullhead City. Spirit Mountain is located just north of Needles, California

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spirit_Mountain_from_Bullhead_City_1.jpg

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Psychodelic_light_effect3.jpg

The Mojave were intensely preoccupied with dreams, through which they believed all of one's talents and achievements derived. During dreaming the individual was believed to travel back to the Great Dark House, to the time of creation when his power was assigned by Mastamhό. Dreams were always forefront of the minds of the Mojave, who constantly discussed and dissected them for evidence that they had been conferred with particular talents.

For the Mojave there were two types of dreams. Ordinary Dreams, or omen dreams, could (when properly interpreted) foretell coming events. However, it was the Great Dreams that all Mojave hoped to receive. These dreams were the ones that conveyed power, but they came to only a few people. The recipients of Great Dreams were pre-ordained to become great leaders such as chiefs, warriors, singers or shamans.

Because a person's talents had been assigned to his unborn soul at the beginning of time, it was believed there was nothing one could do altar his destiny. Powers could not be learned or acquired; one was either destined to be a warrior, or one was not. Although such talents were ascribed before birth, individuals were usually unaware of them until they were revealed in dreams sometime around puberty. All youth longed to receive a Great Dream, and endless time was spent analyzing dreams for clues about the dreamer's destiny. The test of authenticity of dreams was whether the dreamer was able to validate them in successful undertakings.

Source - http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsca/08100/08116r.jpg

A shaman was a specialist who had dreamed the power to cure illness; which illnesses he could cure depended upon which portion of the creation myth he had dreamed and which powers Mastamhό had bestowed upon him. While respected, shamans also led precarious lives and could be killed if they failed to cure people because this would be interpreted as evidence that they were witches.

Shamans and witches were closely linked because when Mastamhό conferred powers to individuals, he gave some of them the power of witchcraft. To all of those same individuals he also gave the power of healing. Thus, all witches are also shamans, but not all shamans are destined to be witches. Which shamans had also been bestowed with witchcraft would only be revealed in the shaman's middle age. Thus, all shamans were viewed with suspicion and fear since any might be revealed to be a witch later in life. Witches, it was feared, would cease to use their powers to heal and instead would use them to bewitch others, especially those that they were particularly close to.

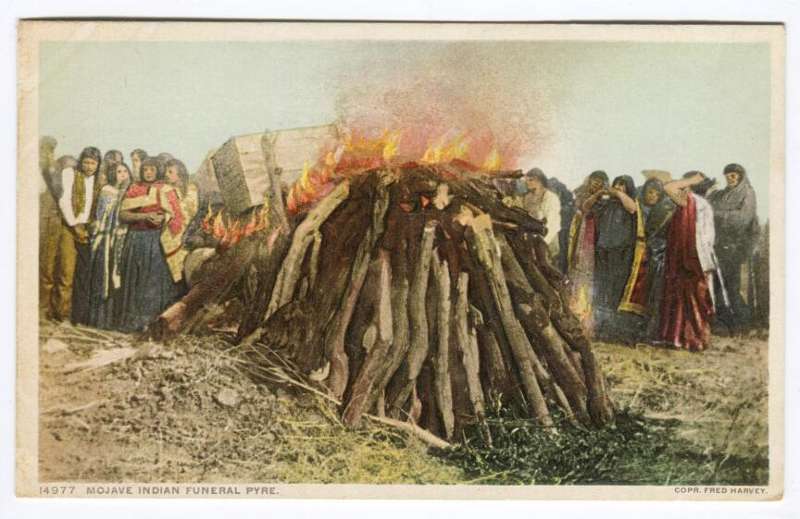

The Mojave had few public rituals. There were no ceremonies with masks or other ritual paraphernalia, and no rituals designed to bring rain or promote crops. Instead, the Mojave emphasized the recitation of dream experiences and the singing of song cycles by individuals predestined to be singers. The Mojave had about 30 different song cycles, each of which had anywhere from between 50 and 100 songs. Singers did not learn these song cycles from one another, but dreamed them in their dreams. During a song cycle, which might take an entire night or more to complete, a singer would alternate between the singing the songs and reciting mythical episodes. Despite the paucity of rituals, the Mojave did have large public mourning meremonies to mark a person's death.

Early 20thcentury postcrd depicting a Mpjave funeral pye

Source - Dr Harry's personal postcard scanned

These ceremonies were patterned after the events that followed the death of Matavilya, the supernatural being born to Sky and Earth. Just as Matavilya's body was cremated and the Great Dark House burned, the deceased's body and possessions (including his house and granary) were set on fire. After cremation, the ghost was believed to go to the land of the dead where it would live in peace with other deceased loved ones. To help the deceased find his or her way, singers would perform a song cycle in which the creation story and the route to the land of the dead would be detailed. The soul did not live in the land of the dead, however, but after passing through a series of transformations eventually ceased to exist and ended up as charcoal on the desert.

|

Aside from dreaming, combat was the primary preoccupation of the Mojave Indians. It was carried out by kwanimas, men who had been conferred their status in great dreams. Those who had received particularly strong dreams were the war leaders.

Kwanamis were men of great prestige. Unlike other men they did not farm but spent their day in a secluded spot meditating on warfare. They were expected to be eager for warfare at all times and to be unconcerned with the normal comforts of life. Kwanamis remained single until middle age, when they were too old for battle.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02801b10.jpg |

A marked distinction existed between raids and warfare. Raids were relatively small-scale affairs which generally involved only 10 to 12 men. They required no real preparation and were launched by restless kwanimis from individual settlements who were wishing for action. Although they might return home with some looted horses or food, raiding seems to have been a secondary goal to that of fighting. Raids were not announced in advance, but were intended to be conducted as surprise raids with the kwanimis attacking and retreating without causing any deaths.

Warfare, in contrast, was a formal pre-planned affair that involved men from throughout the tribe. War parties might be assembled one to two times per year and involve anywhere from between 40 and 100 men. These were major campaigns, ostensibly conducted for revenge, and required substantial advance preparation. Scouts were sent out in advance to reconnoiter the village to be attacked, and a few days before the war party was to depart a call would be sent out for fighters. If it was to be a large battle, members of allied tribes might be invited to join in. These battles were highly organized and executed, with each warrior fulfilling a specific role in a pre-planned battle formation (see Stewart 1947).

A special shaman who was given the power to scalp accompanied the war party. This scalper would accompany the warriors into battle in order to look for an enemy with nice, long wavy hair. He would kill that enemy and take his scalp, but would not scalp anyone else. After the warriors had returned home, the scalper would clean the scalp and display it during the Scalp Dance celebration. The scalper was also responsible for treating any warriors who might have fallen ill because of contact with the enemy.

Warfare seems to have been incessant among the River Yumans. The strong sense of tribal identity made it possible to amass large armies, and alliances with neighboring tribes made warfare and inter-tribal undertaking. Warfare was often undertaken with tribes located more than 150 miles away, and reports indicate that the war parties would sometimes cover as much as 100 miles per day on foot travelling to and from the battleground.

|

Click on next page to continue.

Today, some of the major issues facing the River Yuman tribes have to do with proposed commercial uses of the surrounding desert landscape. Where modern-day policy decision-makers see a barren desert landscape of little cultural or environmental value, the River Yuman tribes see a sacred landscape important to their cultural heritages. These differing viewpoints have often led to clashes between the Yuman people and the U.S. government and commercial companies.

In 1989, the company U.S. Ecology submitted a license application to construct and operate a low level radioactive waste dump at Ward Valley, California, located some 20 miles from the Colorado River and within the traditional territory of the River Yuman people. Because the proposed site was to be located on federal land, a federal permit was needed. Almost immediately all five of the River Yuman tribes expressed concern about radioactive leakage and the potential damage to their ancestral lands. Elders from these tribes made visits to Washington, D.C. to lobby against the facility, and in 2002 the California legislature passed a bill cancelling the project. Every year since then, the Colorado River Indian tribes have gathered in Ward Valley to celebrate this victory.

The fight to protect the Mohave desert landscape continues in tribal opposition to a proposed solar panel field in Imperial Valley. This project called for the construction of 28,000 solar panels in the field, which the Quechan believed would damage the landscape and impact the flat-tailed horned lizard, which plays an important role in their creation legends. In October of 2010 they asked a federal judge to issue an injunction against the project, and in December of that year the court agreed, stating this that additional consultation and research was required before the project can be approved. After posting financial losses, the solar project was subsequently abondoned by the solar company, though additional solar projects in the area are in the works.

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nellis_AFB_Solar_panels.jpg

Practice Quiz # 8