Upland Yumans

Module 9

The Upland Yumans were hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists (unintensive farmers) who inhabited a vast and rugged territory in what is now north-central and northwest Arizona. This area is elevationally diverse, containing altitudes ranging from less than 1800 feet to more than 7000 feet above sea level. This elevational diversity results in substantial environmental diversity, which the Upland Yuman people exploited by travelling seasonally back and forth between the pine-covered plateaus and the hot, sage-covered deserts. Two tribes comprised the Upland Yumans; the Pai (the Havasupai and Hualapai) and the Yavapai. Although members of the two tribes spoke the same language, the Pai and the Yavapai were traditional enemies and considered themselves to be separate people. Today, the Upland Yuman people live on five reservations, one occupied by the Hualapai, one by the Havasupai, two by the Yavapai, and one by both Yavapai and Apache.

Instructions: Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between Upland Yuman Past Territories and Upland Yuman Modern Reservations pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

Griffin-Pierce Chapter 8

The following videos are optional for your exploration but highly encouraged.

Videos showing how agave hearts are roasted

Video of Pai bird dancers

Click on next page to continue.

The prehistoric background of the Upland Yumans is poorly understood. Like their linguistic relatives along the lower Colorado River, they are believed to have descended from the prehistoric Patayans. Sometime during the late prehistoric record, some of the lowland Patayan people moved into the upland areas. There, they lived a fairly mobile life, constructing temporary brush structures and leaving behind the tell-tale buff-colored pottery that identifies them as Patayan. Other than these ephemeral remains, archaeologists have few clues to help us understand what life was like for these early Upland Patayan people.

Early accounts indicate that historically there were thirteen Pai bands which maintained separate but overlapping ranges. These thirteen bands were loosely grouped into three subgroups, known as the Middle Mountain People, the Plateau People, and the Southern Rim People. Despite these various divisions, all Pai considered themselves to be the same people. Although the two surviving bands are today politically distinct entities, this is the result of U.S. policy.

To the south of the Pai people lived the Yavapai. Although they spoke the same language and descended from the same people, the Pai and Yavapai were bitter enemies.These hostile relations seem to have stemmed from the fact that the Yavapai, who rarely farmed, regularly raided the stored food supplies of the Pai.The Yavapai often allied themselves with the Apache, with whom they were often confused by the Anglos.

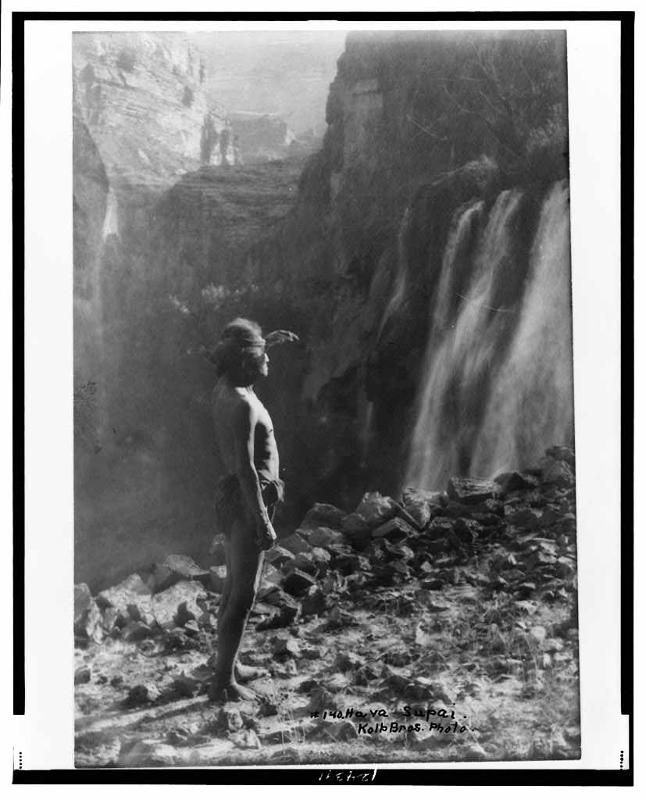

Havasupai man, 1911

Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99471896/

Click on next page to continue.

|

Early Spanish explorers reported seeing tribes wandering in the territory occupied by the Pai, but due to remoteness of this area and the tribes' semi-nomadic nature little was known about them until the arrival of European trappers and explorers in the late 18th century. Over the next century, the other Pai bands either disappeared or were absorbed into the Haualapai and Havasupai bands. The Havasupai, whose name means "people of the blue-green water," are so-named for the impressive waters found in Cataract Canyon, the area where they lived for part of each year. This area, with its permanent rivers and lush waterfalls, has been referred to as the "Shangri-La" of the American West. The Hualapai (also sometimes spelled Walapai), or "people of the tall pines," inhabited the plateaus and canyons to the west of the Havasupai.

|

Cataract Canyon, Havasupai, Arizona Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-125691077/stock-photo-beautiful-havasu-falls-supai-arizona.html?src=q55CSqUyWkIlXf1tlNbuSg-1-44 |

Click on next page to continue.

Before the Pai were confined to reservations, they followed a seasonal round focused on several key plant foods. Of two bands, the Havasupai relied on farming to a larger degree than the Hualapai and the seasonal rounds of the two bands varied slightly as a result.

For the Havasupai, the agricultural season began in mid-April when they returned to their summer settlements in the bottom of Cataract Canyon. There, they planted fields and constructed small irrigation ditches to water their crops. Harvesting began in June and continued until early fall, with the produce dried and stored for winter use. By mid-October the crops had all been harvested and the Havasupai returned to their winter homes on the plateau, taking their dried foods with them. There, they hunted deer and rabbit and harvested pinion nuts and other wild resources until it was time to return to the lowlands the following spring.

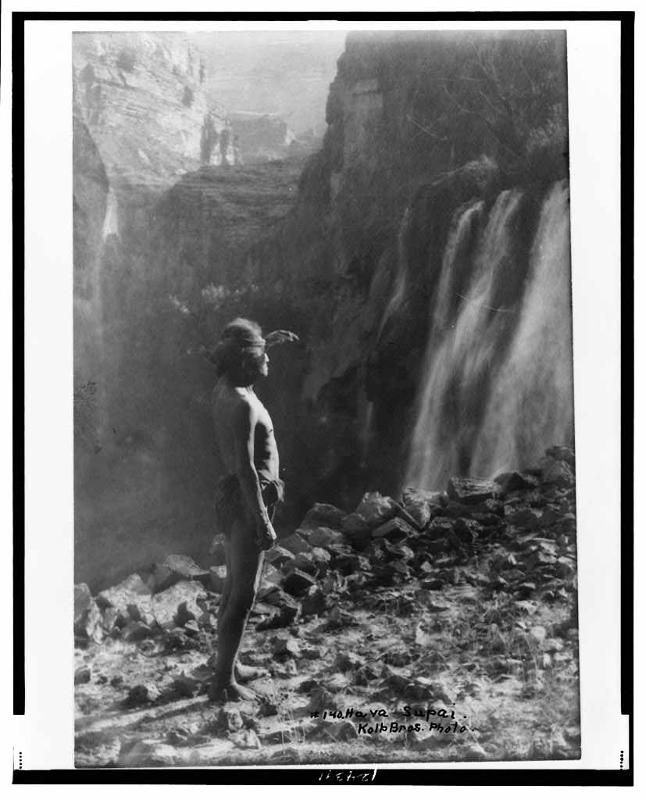

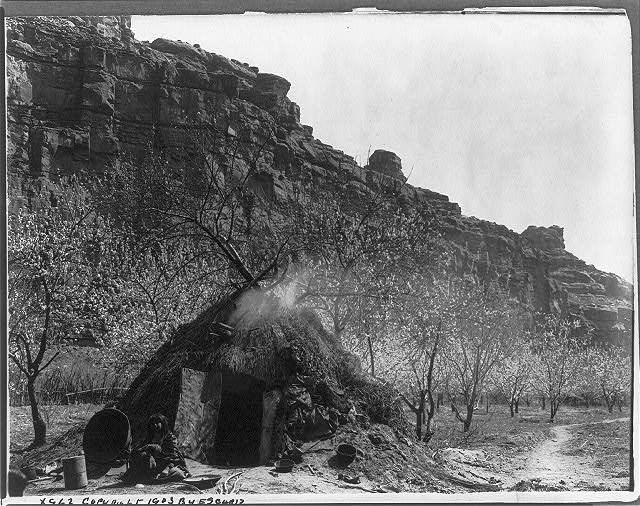

Havasupai woman seated in doorway of summer wickiup in Cataract Canyon, ca. 1903.

Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652734/ Photograph by Edward S. Curtis.

The Hualapai spent far less time in one place. Rather than having two major moves during the year, they moved frequently to take advantage of plants ripening in different elevational zones. Early spring was spent camping in canyons and foothills where they gathered and processed large quantities of agave plants. Once collected, the leaves would be removed and the hearts baked in underground pits for several days.

Video one shows the setting up of the pit for an agave roast at the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix Arizona, along the Plants & People of the Sonoran Desert Loop Trail

Video two shows how the roast is done and people tasting the agave roast.

|

The non-fibrous inner core (which the cooking process converted into a sticky sweet substance, something roughly between the taste and texture of a dried apricot and a gummy worm) would be eaten right away, while the outer layers would be crushed into a pulp, dried in the sun, and stored. These dried slabs would later be boiled and then either eaten or mixed with water to produce a tasty beverage. The stems and leaves would be used to make sandals and cordage. |

|

|

Agave hearts, prepared for baking

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-291152354/stock-photo-agave-field-for-tequila-production-jalisco-mexico.html?src=ND6L2RxhKn8JC4d3BmoCWw-1-54 |

Agave Plant

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Agave_arizonica_2.jpg |

|

Following the agave harvest, the Hualapai moved down to the canyon bottoms to gather wild resources and to plant crops. At the time of contact the Hualapai reportedly invested little effort or care in their crops, though some oral histories suggest that farming had been emphasized more in earlier times. After spending a few weeks in the canyon bottom, they moved back into the canyons and foothills to gather the fruit of various cactus, returning occasionally to check on their crops. Late summer and early fall were spent on the plateaus collecting pinion and juniper nuts, and winter was spent in large encampments on the plateau.

|

|

Click on next page to continue.

|

Despite their involvement in agriculture, both the Havasupai and the Hualapai considered themselves to be foragers whose main homes were on the plateaus. For much of the year they lived in small family groups comprised of perhaps 20 people, but in the winter the entire band would aggregate together in large villages on the plateau. Bands were grouped into one of three subtribes, but subtribal boundaries were not clearly demarcated either socially or spatially. Bands from one subtribe were welcome into the territory of another during periods of food abundances and marriages often occurred across the subtribes. Each family camp and winter settlement had headmen, but—like their lowland counterparts—these leaders had little formal authority.

|

|

|

The pai lived in dome-shaped huts constructed of poles and branches, wore rabbit-skin robes to keep them warm in the winter, and tattooed and painted their faces.

They also maintained widespread trade networks that created strong social ties with neighboring groups. Both groups participated in a trade network that moved goods to and from as far away as the California Coast and northern New Mexico. The Hualapai, who harvested fewer crops that the Havasupai, would (during times of peace) trade deer and other meat to the Mohave in return for supplies of corn and beans. The Havasupai had particularly close trade relations with the Hopi, which provided opportunities not only for exchange of goods but for the creation of close social ties.

Pai home, showing construction of wickip. Circa 1901. Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/95502974/,Photographer: Henry G. Peabody. |

Pai (or possible Mohave) man wearing rabbit skin robe,1907. Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90710179/ ,photographed by Edward S. Curtis. Historic accounts indicate that during times of drought Hopi families sometimes moved in with their Havasupai trading partners. Similarly, some Havasupai elected to go live with the Hopi during the harsh winter months. |

|

The close relationship between the Hopi and Havasupai is reflected in this 1899 drawing of a "Kohonino" katchina, who is interacting with a Hopi impersonating a Havasupai. The "kohonino" was the name given to the Havasupai by the Hopi.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/4731/08547310.jpg |

Like the Yumans that lived along the Colorado River, dreaming and shamanism played a major role in their culture. Most shamans were medical practitioners, but others had powers that allowed them to control the weather or ensure hunting successes. Like the River Yumans, these shamans received their powers in dreams. Their mortuary customs also paralleled those of the River Yumans, with the deceased's body being cremated at death and his or her personal property being destroyed

The major ceremony of the Havasupai was the harvest dance held each fall. This ceremony was a major event, lasting several days, and was attended not only by all Havasupai but by Navajos, Hopis, Hualapais , and sometimes even the more distant Zuni. This festival provided an opportunity for feasting, bartering, and visiting and was considered a major social event. Today, this harvest festival continues in the form of the Peach Festival, which is held in August to accommodate the children's boarding school schedules. This festival attracts both Indians from neighboring tribes and Anglo tourists, and today includes not only the traditional feasting and bartering but a rodeo and pageant as well. |

Click on next page to continue.

When gold was discovered near Prescott, Arizona in the 1860s, large numbers of prospectors entered the area and hostilities between the Pai and the Anglos soon erupted. Warfare broke out with the Hualapai,who were soon defeated and forcibly relocated to La Paz, an internment camp on the Colorado River. They remained there for one terrible year, during which time many died from diseases, food shortages, and the arduous labor that they were forced to endure. In 1872 the Hualapai fled La Paz, returning to their homeland. However, during their absence Anglo ranchers and miners had colonized the habitable areas near springs and had introduced large herds of cattle elsewhere. To keep the Hualapai off of these lands, in 1883 Congress established a reservation for them on lands that one Bureau of Indian Affairs official called "the most valueless land on earth for agricultural purposes." Unable to make a living on the reservation, less than a dozen Hualapai actually lived there, with the remaining seeking jobs in nearby mines and towns.

Like the Hualapai, the Havasupai were impacted by the influx of settlers into their territory. As conflicts increased the U.S. Government offered them a 518-acre reservation in the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Reluctant to give up their winter lands, the Havasupai nonetheless accepted in order to avoid the harsh internment that they witnessed for the Hualapai. Their reservation was established in 1880 in Cataract Canyon, the place of their traditional summer homes and under the watchful eye of Wii'gleva, the twin rock pillars that serve as their guardian spirits. The Havasupai believe that as long as these pillars stand the Havasupai people will be safe.

The Havasupai, however, found it difficult to adapt to year-round settlement in the canyon. The reservation was not large enough to support the population and the Havasupai found the canyon cold, dark and bleak during the winter. As a result, many Havasupai continued to winter on the plateau in small settlements hidden in remote areas of their former territory. Shortly after the Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, park rangers put an end to this practice and the Havasupai spent the next several decades fighting to have their plateau lands returned to them. In 1975, the U.S. Government returned 185,000 acres of canyon and rim territory to the tribe but restricted how the tribe could use that land. In particular, the tribe is not allowed to develop any tourist enterprises on that land.

Horses grazing beneath the twin rock pillars Wii'gleva, the guardian spirits of the Hualapai

Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Watchers2.JPG

Click on next page to continue.

Today, the Havasupai and Hualapai—who once considered themselves the same people-- are recognized by the federal government as two distinct tribes. The Hualapai tribe now numbers 2300 people, of which about 1300 live on the reservation. After several decades of relying on off-reservation jobs for their income, in the 1960s the Hualapai began to develop recreationally-based programs to attract outdoor enthusiasts and tourists. Today, the tribe operates several tourist-based attractions, including lodges, a river rafting company, and a glass walkway for viewing the Grand Canyon. This Grand Canyon Skywalk, which opened in 2007, extends some 4000 feet above the Colorado River.

Grand Canyon Skywalk on the Havasupai Reservation.

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-369264470/stock-photo-amazing-view-grand-canyon-skywalk-arizona-usa.html?src=w5f2_geb5GCpjbTjgXHbeg-1-2

Tourist at Mooney Falls, Havasu Canyon.

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-11000047/stock-photo-young-man-sitting-on-a-cliff-watching-mooney-falls-drop-into-it-s-turquoise-pool-havasu-canyon.html?src=6LooGo5mi-Oi-CzEp4rtNA-2-32

Like the Haualapai, the Havasupai today also rely largely on income from tourism. Some 450 of the 650 tribal members currently live in Supai, their town in the bottom of Cataract Canyon. Supai is extremely remote and even today the only way to get into or out of the canyon is by foot, horse, or helicopter. However, the canyon's lush waterfalls and clear blue waters attract some 12,000 visitors per year, all of whom pay fees to visit. The tribe also operates a campground and hotel in the canyon and offers a mule service to carry passengers and/or their luggage into and out of the canyon.

One of the major issues concerning the Havasupai and Hualapai today is uranium mining. Since the 1950s, uranium mining has been big business on the Colorado Plateau, but because of the harmful legacy of this activity on the Navajo reservation (see Navajo module for more information) most tribes within this region have banned it on their reservation lands.

In the 1990s, the Canadian-based Denison Mines Corporation requested groundwater-aquifer permits from the state of Arizona that would allow them to re-open three mines within and around the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai and Hualapai immediately launched protests, arguing that the opening of these mines threatened their drinking water and traditional religious areas. One of the mines is near Red Butte, a Havasupai sacred site that is where the Havasupai first came into being a separate people. Despite these concerns, in March 2011 Arizona regulators approved the Denison Mines Corporation's request for the groundwater-aquifer permits. Before the mines can re-open the corporation still must obtain federal approval.

One of the major issues concerning the Havasupai and Hualapai today is uranium mining. Since the 1950s, uranium mining has been big business on the Colorado Plateau, but because of the harmful legacy of this activity on the Navajo reservation (see Navajo module for more information) most tribes within this region has banned it on their reservation lands.

In the 1990s, the Canadian-based Denison Mines Corporation requested groundwater-aquifer permits from the state of Arizona that would allow them to re-open three mines within and around the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai and Hualapai immediately launched protests, arguing that the opening of these mines threatened their drinking water and traditional religious areas. One of the mines is near Red Butte, a Havasupai sacred site that is where the Havasupai first came into being a separate people. Despite these concerns, in March 2011 Arizona regulators approved the Denison Mines Corporation's request for the groundwater-aquifer permits. Before the mines can re-open the corporation still must obtain federal approval. The fight against uranium mining thus continues for the tribes.

Click on next page to continue.

The Yavapai were a primarily foraging people who lived in central and west-central Arizona. Prior to being confined on reservations the Yavapai roamed over a large territory that spanned more than 10 million acres. Their culture reflects their Yuman origins but also is heavily influenced by that of the Apache who lived to their east.

Yavapai territory

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=65806960&src=id

The settlement and subsistence pattern of the Yavapai was similar to that of their Hualapai neighbors. Small extended family groupings followed seasonal rounds that cycled through different elevational zones, to take advantage of the different seasons of food availability. Agave and pinion nuts were staples of their diet, and some groups practiced limited horticulture by planting in washes or near springs and returning intermittently between their hunting and gathering trips to check on the crops. The period of greatest abundance was fall, when the nuts, berries and seeds of the uplands were ripening. To ensure that they would have enough to eat during the barren winter season, foods would be dried and cached in caves during the other seasons.

Like other Yuman groups, the basic Yavapai social unit was the extended family. These small kin groups travelled together on their seasonal rounds, only aggregating into their larger band settlements during the winter. Winter camps were usually set up in caves, though in areas where there weren't caves dome structures like those used by the Pai were constructed. The Yavapai had four subtribes.

Yavapai culture was heavily influenced by the Apache. Their origin myth contains both Yuman and Apache elements and ceremonies from both cultures were practiced. As did other Yuman groups, they performed the Bird Dance (watch video), a ceremony in which girls impersonate birds and song cycles relate stories about nature. They also held girl puberty ceremonies and Mountain Spirit Dances (or Crown Dances) borrowed from the Apache. (These ceremonies will be discussed further in the Apache module).

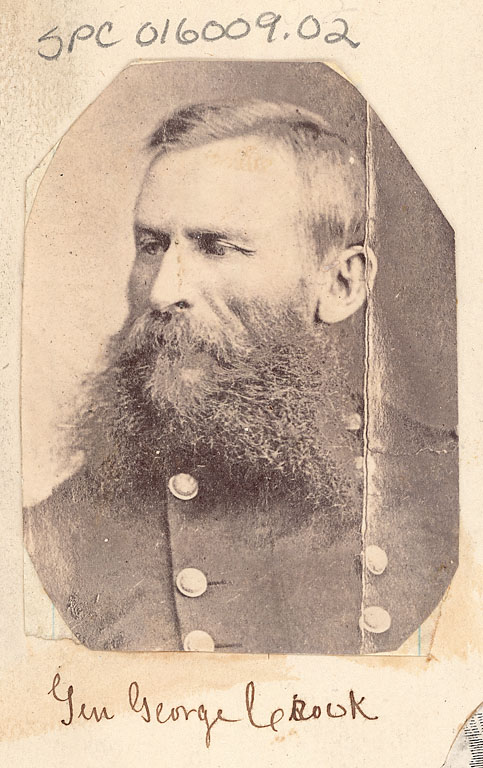

Like that of the other tribes, the Yavapai hunting and gathering lifestyle came to an end in the 1850s. As the influx of settlers limited their ability to follow their traditional seasonal rounds, the Yavapai increasingly turned to raiding Anglo settlements for food. This resulted in a ten-year long war between the Yavapai and the U.S. Calgary known as the Yavapai Wars. In 1871, General George Crook was put in charge of the Arizona territory and tasked with moving all "roving" Indians to reservations. On December 21, 1871, Crook issued an edict that all Indians not on the reservation by February 15, 1872 would be treated as hostile. It is unclear if the Yavapai- who were hiding in small groups across their territory- ever received this message.

Portrait of U.S. General George Crook.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/4605/01600902.jpg

The following winter General Crook initiated a program of systematically destroying the stored food caches of the Yavapai. Without these food stores the Yavapai were quickly reduced to the verge of starvation. In December of 1872, his army located a cave containing a band of Yavapai and opened fire, killing 76 of the 110 Yavapai men, women and children living there. This event is known as the Skeleton Cave Massacre, and is still remembered by the Yavapai as the most horrendous event of the war.

Without their winter supplies and facing certain starvation, the remaining Yavapai soon surrendered and by spring of 1873 most were on a reservation in the Verde Valley. Despite an epidemic that killed about one-third of their people, they managed to excavate an irrigation ditch and produce a successful harvest that year. Concerned by the growing self-sufficiency of the Yavapai Indians, a group of Tucson contractors (who sold food rations for use on the reservations) pressed to have them relocated to the Apache Reservation at San Carlos. The next winter the Yavapai were forced to walk 180 miles over rugged terrain to reach the San Carlos reservation; although 1500 Yavapai began the journey, only 200 remained alive when they returned more than a decade later.

Although the Yavapai and the Apache were traditional allies, the Yavapai were the minority at San Carlos and wanted their own reservation. Between 1903 and 1905 this request was honored, and the Fort McDowell, Yavapai-Apache, and Camp Verde reservations were established. Each of these reservations has developed separately and today house separate tribes with separate governments.

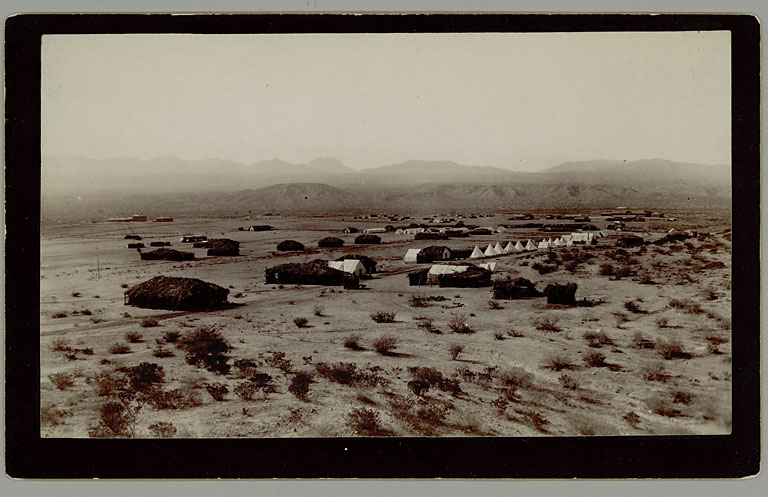

San Carlos Indian Reservation.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/apache/02008300.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

After moving to their three reservations, most Yavapai made a living through a combination of farming and wage labor. Farming on the Fort McDowell reservation, however, was made difficult by the regular flooding of the Verde River, which repeatedly damaged their irrigation systems. Frustrated with spending money to repair these systems, in 1906 the Bureau of Indian Affairs recommended that the McDowell farmers be relocated to the Salt River Pima Maricopa Reservation. With the help of Dr. Carlos Montezuma, the Yavapai fought to retain their lands and water rights. Dr. Montezuma, a Yavapai Indian, had been captured by Pima Indians as a boy and subsequently sold to a white man. Raised in Chicago, he went on to earn his medical degree before returning to Arizona and becoming Indian rights activist.

In the 1970s the community faced a new threat, in the proposal by the federal government to construct Orme Dam. This dam would have flooded nearly 65% of the Fort McDowell reservation, but the government finally abandoned the plans in 1981 after substantial opposition from the Yavapai people.

Carlos Montezuma.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/73/06702900.jpg

Practice Quiz # 9