The Navajo

Module 10

The Navajo are an Athapaskan-speaking people whose ancestors arrived in the American Southwest at around A.D. 1400. At contact, their ancestors lived in the four corners region of the American Southwest in an area roughly bounded by Hesperus Peak, Blanca Peak, San Franciso Peak, and Mount Taylor. These four sacred peaks of the Navajo mark their traditional homeland, which they refer to as Dinetah.They were forcibly removed from this homeland in 1863, but allowed to return four years later when the Navajo reservation was established. Initially only 5,000 square miles, it was successively enlarged over the years and today—at more than 27,000 square miles—it is larger than ten states and is the largest Indian reservation in the United States. With more than 300,000 people on its rolls, the Navajo Nation also is the largest tribe in terms of population.

Instructions:Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between Dinetah, 1868 Navajo Reservation and Modern Navajo Reservtion pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

The earliest Spanish accounts indicate that the Navajo and Apache (who are closely related) lived broadly similar lives, with the major difference being the greater emphasis that the Navajo placed on farming. As a result, the Spaniards referred to them as "Apache de Nabajo," using the Tewa word ("Na-ba-ho") for planted fields. The Navajo name for themselves is Diné, which means "The People." In the late 17th and early 18th centuries the Navajo selectively adopted certain aspects of Puebloan and European cultures, and the fusion of these three cultures—Athapaskan, Puebloan, and European—led to the creation of what today is considered traditional Navajo culture.

The most important of the adopted practices included sheep raising and weaving, both of which continue to play major roles in Navajo society.

For information on Navajo Code Talkers:

Watch the video for information on Navajo uranium mining water contamination

If you have trouble viewing the video, click on this link - https://news.vice.com/video/living-without-water-contamination-nation

Click on next page to continue.

|

The Navajo and Apache are related to the northern Athapaskan Indians, such as the Sarcee tribe from Canada, shown here. Note the similarity in dwelling styles. Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=97507231 The Navajo and the Apache are the only Southwestern Indians whose languages belong to the Athapaskan language family; other Athapaskan speakers live far to the north in Canada, Alaska, and on the Pacific Coast. Evidence suggests that about one thousand years ago some of the Canadian Athapaskans begin to migrate southward, eventually arriving in northwest New Mexico at about 1400 A.D.

During this long trek the Athapaskans—who in Canada had lived as hunter-gatherers adapted to a cold climate— adjusted to the environments they encountered by readily adopting new technologies along the way. This resilience—the willingness to change and adapt while retaining core aspects of their identity-- remains a key trait of the Navajo today. |

|

The Athapaskans entered the American Southwest in small, extended family groups. These early Athapaskans shared a similar hunting and gathering lifestyles. Over time, these groups spread into different ecological niches and became differentiated from one another. Some groups remained in northern New Mexico and adopted farming from the puebloan cultures; it is their descendants that are the Navajo. When the Spaniards arrived in the early 16th century, the Diné were a semi-nomadic people living in northern New Mexico in the homeland that they called Dinetah. These early Diné lived in extended family groups and alternated their time between hunting and gathering and farming activities. However, it wasn't until after Reconquest of 1692 that the culture we identify as "Navajo" crystallized. In Module 2, we learned about the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in which the Pueblo Indians defeated the Spanish and drove them from northern New Mexico. We also learned about the Spanish Reconquest of the region twelve years later, when Spaniards were able to regain control of this territory. The Diné participated in the Pueblo Revolt and, when the Spaniards returned to defeat the Puebloans, allowed Puebloan refugees to settle in their territory. It was during this post-Reconquest period, when the two groups of people lived side by side, that the Diné incorporated certain puebloan practices and beliefs into their culture and the distinctive Navajo culture emerged.

Simon Canyon Pueblito, a Navajo and Puebloan site occupied after the Re-conquest. The Navajo borrowed the idea of masonry structures from the Pueblo Indians to build towers that could be used as lookouts. To avoid Spanish reprisals, these post-Reconquest settlements were commonly built in defensive locations. Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pueblito_in_Simon_Canyon.jpg |

|

In the 1700s the Navajo were forced to expand out of their homeland due to droughts and raiding from Ute Indians. Initially, the movement out of Dinetah was peaceful, but by the middle 1800s Anglo settlers were losing massive numbers of livestock to Navajo raiding. When the region came under U.S. jurisdiction in 1848, the settlers demanded protection. When Brigadier General James Carleton was appointed military commander over the region in 1862 he decided the only way to resolve the problem was to relocate the Navajo out of the region. In April of 1863, he proclaimed that the Navajo had until July 20 to turn themselves and be relocated to Bosque Redondo, an Indian Reservation on the Pecos River. The next fall, under the direction of General Carlton, a reluctant Kit Carson initiated a "scorched earth campaign," in which Navajo livestock were confiscated and their fields, houses, and orchards burned down. Later that winter large numbers of starving Navajo begin to turn themselves in. Ultimately, some 9000 Navajo surrendered and made the long, 300+ mile trek from Fort Defiance to the Bosque Redondo. During this trek, which was made on foot and in winter, the Navajo faced unbelievable hardships and many died from exposure to the cold and from starvation and exhaustion. Those who could not keep up, including pregnant women who went into labor, were shot by soldiers. This trek, known as the Long Walk, remains deeply etched in the collective memories of the Navajo today. The Navajo were imprisoned at Bosque Redondo for four years, at a cost to the U.S. government of two million dollars. Conditions on the reservation were horrendous and resulted in the deaths of many more Navajo from dysentery, small pox, and poor living conditions. By all accounts, the Bosque Redondo effort was considered a massive failure. After numerous newspaper stories were run detailing the suffering of the Navajo and the economic costs of the policy, Carleton was relieved of his command and the Navajo given a reservation (within their original homeland) in 1868.

Navajos at Bosque Redondo under guard, ca. 1864-1868. Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hweeldi3.jpg

|

|

Upon their return to their homeland the Navajo were given 14,000 sheep by the U.S. government; by 1892, these herds had expanded nearly one hundred fold. As their herds grew the Navajo population also grew, and several additions were made to their reservation to accommodate their increasing need for space. In addition to sheepherding, the Navajo entered the market economy by producing items such as woven blankets and silver jewelry which were in demand by the growing tourist economy. In short, whereas the Navajo returned from their incarceration at Bosque Redondo an impoverished people, in only a few decades they were able to transform themselves into a thriving and economically independent people. This economic independence was shattered in the 1930s as a result of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) stock reduction program. In 1933, the BIA determined that as much as two-thirds of the Navajo range had been destroyed by overgrazing and instituted a program to thin the herds against the wishes of the Navajo. The inhumane methods used to kill off the herds and the insensitivity in how the program was instituted angered the Navajo and, like the Long Walk, is remembered with bitterness today. The stock reduction program, along with the Great Depression, ushered in a period of dependence on the wage economy and welfare for the Navajo people. In World War II, the military enlisted Navajo to transmit secret communications using their native language. For those words which had no Navajo equivalent, Navajo words were assigned new meanings. For example, the Navajo word for "egg" was used for "bomb," and the Navajo word for "hummingbird" was used to indicate "fighter plane." The code created and used by the 420 Navajo Codetalkers, as they came to be known, is the only code that was never broken by the Japanese.

Dan Akee, World War II Veteran and Navajo Code Talker, being honored during Native American Heritage Month. National Park Service photograph taken by Erin Whittaker on November 18, 2010. Source - http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a6/Dan_Akee%2C_Navajo_Code_Talker.jpg |

Click on next page to continue.

Navajo lifeways reflect a constellation of Athapaskan, Puebloan, and European cultural traits. Reflecting their Athapaskan roots are Navajo beliefs about death, the emphasis on individuals and shamanism in their ceremonies, and their use of conical dwellings. Traits adopted from the Pueblo Indians include farming, pottery, weaving, and the use of a clan system. And finally, from the Europeans (but via the Pueblo Indians) they obtained livestock (especially sheep) and certain agricultural crops such as peaches and wheat.

Navajo lifeways reflect a constellation of Athapaskan, Puebloan, and European cultural traits. Reflecting their Athapaskan roots are Navajo beliefs about death, the emphasis on individuals and shamanism in their ceremonies, and their use of conical dwellings. Traits adopted from the Pueblo Indians include farming, pottery, weaving, and the use of a clan system. And finally, from the Europeans (but via the Pueblo Indians) they obtained livestock (especially sheep) and certain agricultural crops such as peaches and wheat.

Traditional Navajo subsistence is based primarily on sheep-herding and farming. Sheep were considered an important source of power; the person who wielded the most power was usually the person who had the most and best sheep. Until the mid-nineteenth century, Navajo lived in dispersed settlements and followed a bi-seasonal settlement pattern that rotated between summer and winter homes.The basic economic and social unit was the matrilocal extended family, which was organized around the head mother, the sheep herd, and a land-use area. Within this group, sheep were individually owned but jointly managed and fields were jointly used. The tasks of lambing and shearing were shared by the entire residence group.

Above the extended family was a loosely knit unit called the outfit. The outfit consisted of a group of relatives who lived near one another and who cooperated for certain ceremonial or other purposes. The largest kin group was the matrilineal clan but, other than regulating marriage (one could not marry within a their own or a related clan), the clan had few functions. The Navajo did not share any sense of a tribal consciousness until after their return from Bosque Redondo.

Sheep on the Navajo reservation

Source - http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=16414153&src=id

Click on next page to continue.

The most important Navajo deity is Changing Woman, who was born in Dinetah and who there created the first corn and the first Navajo people. Changing Woman was reared by First Man and First Woman who marked her transition to womanhood with the first girls' puberty ceremony, called a kinaalda. Changing Woman, who is reborn each spring before maturing and then dying the following winter, represents change and rebirth to the Navajo people.

The Diyin Diné'e, or Holy People, are other important supernatural beings in the Navajo belief system. These beings live in the underworld and, though not human, have the power of speech and live and act like people.

The Diyin Diné'e, or Holy People, are other important supernatural beings in the Navajo belief system. These beings live in the underworld and, though not human, have the power of speech and live and act like people.

Though they cannot be seen on earth in their human forms, they often inhabit material and living objects such as mountains, plants, and animals. The Diyin Diné'e are for the most part indifferent to human lives, but they may be persuaded to come to their aid through certain ceremonies.

The Holy People are thus neither conceived of as innately good or bad but, because the underworld in which they live is associated with disorder, violence and witchcraft, contact with them is perceived to be dangerous.

Another important concept to the Navajo is that of hózhó. Although there is no single English word that encompasses its meaning, hózhó roughly means something along the lines of beauty, harmony, goodness, and order.

The world that Changing Woman was born into is said to have been one of hózhó, and it is this state that Navajo strive to reach and recreate.

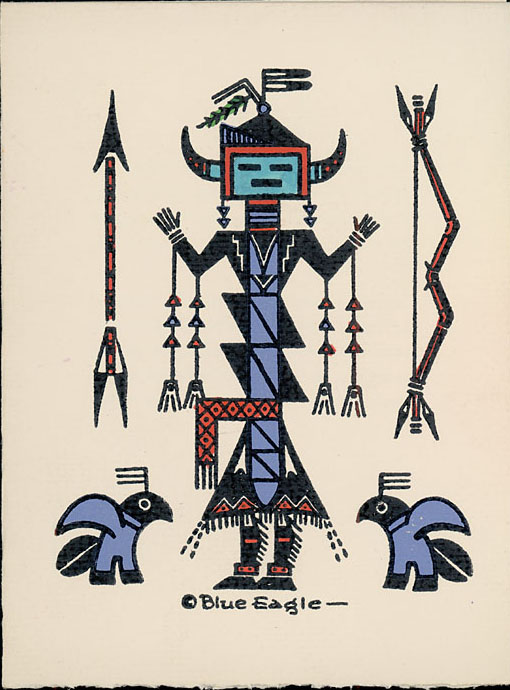

Drawing of a Navajo Diyen by Acee Blue Eagle

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/74-7/08776400.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

When the world is in a state of hózhó there is no illness or misfortune. However, many things can throw the world out of balance, including ghosts, lightening, snakes, coyotes, and bears. Navajo ceremonies are designed to restore hózhó when this happens. Such ceremonies can be conducted in order to bring about healing or simply to ensure general well being or wealth.

When the world is in a state of hózhó there is no illness or misfortune. However, many things can throw the world out of balance, including ghosts, lightening, snakes, coyotes, and bears. Navajo ceremonies are designed to restore hózhó when this happens. Such ceremonies can be conducted in order to bring about healing or simply to ensure general well being or wealth.

Whether the goal is healing or general well being, all ceremonies are designed to attract the attention of the Diyin Diné'e in order to persuade them to bestow blessings and restore hózhó. The Diyin Diné'e are attracted by carefully following ceremonies that can include rituals, chants, and sandpaintings. If the performance is judged to be correct and complete, the Diyin Diné'e will come.

The Navajo ceremonial system is extremely complex, involving numerous "chantway" ceremonies. For example, Enemyway ceremonies are used to exercise ghosts and are used to protect warriors for slain enemies; Blessingway ceremonies are conducted to invoke blessings, and may be held whenever a new home is completed, a woman is in childbirth, or to protect livestock; and Nightway ceremonies are healing rituals. Within each of these general categories there are numerous rituals and which should be used will depend on the goal of the ritual and the cause (in cases of illness) of the misfortune. For example, because insanity can be caused by coming in contact with a moth, the Mothway chant (a type of Nightway ceremony) is used to heal mental illness. Rheumatism, sore throats, and stomach problems can be caused by contact with a snake, and require that a Beautyway chant be performed.

If a person is sick a hand trembler must be hired to determine the cause of the illness; a hand trembler is a specialist capable of determining the causes of illness while in a trance-like state. After determining the cause, and thus which ritual should be performed, a hataali (or a ritual singer) will be hired to carry out the ceremony. To correctly carry out the ritual, the hataali must have memorized hundreds of songs, dozens of prayers, and numerous complicated and intricate sand paintings, for if a single error is made in carrying out the ritual, the Diyin Diné'e will not come. Because of the complexity of the rituals, most hataali know only one or two of the dozens of ceremonies used in Navajo society.

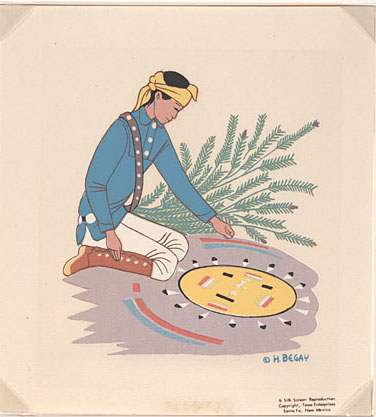

Drawing of a Navajo man making a sand painting, by Harrison Begay

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/74-7/08788300.jpg

Many rituals require the use of sandpaintings. These large images (most measure about six feet across) can be quite complicated and must follow precise standards; they can take four to six men anywhere from between three and five hours to complete. The sandpainting image attracts the Diyin Diné'e, who then reciprocate by bestowing the image with healing power. The patient is healed by sitting on the image to absorb its healing power; afterwards, the sandpainting is destroyed to rid the danger that is now associated with it.

Navajo men working on a sandpainting, ca. 1890-1910

Source - https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/Navajos_sandpainting.jpg

Perhaps the most important ceremony in Navajo society is the kinaalda, the girl's coming of age ceremony. Patterned after the puberty ceremony first held for Changing Woman, a girl's kinaalda spans four days. During the kinaalda other other women work her body with their hands in an effort to "re-mould" her into the image of Changing Woman, the ideal woman. On the final day, once she is a woman, the girl will lay her hands on others in the community to bestow blessings. Watch the video (below) on kinaalda.

Click on next page to continue.

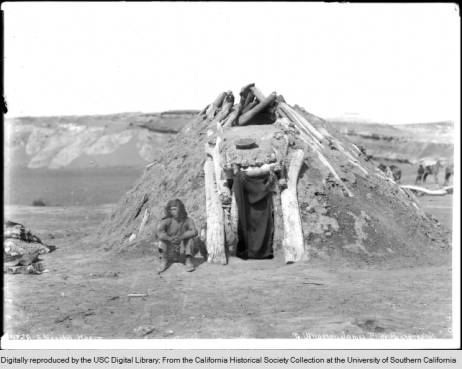

Navajo man sitting in front of his Hogan, ca. 1900. Hogan is in early style, constructed using the forked stick technique.

Source - http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15799coll65/id/17055/rec/1

Like other Athapaskan groups, the traditional home of the Navajo was the hogan, a rounded a domed structure. The earliest Navajo hogans were constructed of forked sticks covered with mud, but by the late 1800s these had been replaced by roomier, hexagonal or octagonal structures made of cribbed logs.

Although most Navajo today live in trailers or wood or brick homes, hogans are still very common on the Navajo reservation and hold an important place in Navajo rituals and identity.

The hogan is patterned after the first structure made by First Man, which is also the structure in which Changing Woman's kinaalda was held. Thus, hogans are still used for important ceremonies, including the kinaalda.

Later style hogan made of cribbed logs, 1940.

Source -https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/fsa/8b24000/8b24500/8b24565r.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

|

The earliest Diné did not weave but wore buckskin clothing. During the Re-Conquest the Diné adopted both sheepherding and weaving from the Pueblo Indians. Instead of weaving cotton as did the Pueblo Indians, however, the Navajo wove wool obtained from their sheep. Although initially they wove primarily clothing for their own use, by the late 1800s they made rugs for Anglo markets. By the early 20th century, Navajo rugs had become a major source of income for the Navajo and it continues to be so today. Navajo blanket.

|

Silverworking also came to be closely identified with the Navajo. While at the Bosque Redondo the Navajo men learned silverworking, and after returning to their homeland several began to set turquoise into a silver overlay. As with the Navajo rugs, Navajo jewelry became a sought-after tourist souvenir. |

|

19th century Navajo blanket, from 1914 book on Native American textiles Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Navajo_blanket.jpg

|

Navajo silverwork belt Source - shutterstock_42918886-2.jpg

|

Click on next page to continue.

Perhaps the largest issue facing Navajo today is economic underdevelopment. Much of the Navajo Reservation is remote, with many areas being accessible only by four wheel drive or horse or (particularly in winter) by helicopter. This lack of accessibility has made it difficult for many Navajo to find employment and educational opportunities.

Perhaps the largest issue facing Navajo today is economic underdevelopment. Much of the Navajo Reservation is remote, with many areas being accessible only by four wheel drive or horse or (particularly in winter) by helicopter. This lack of accessibility has made it difficult for many Navajo to find employment and educational opportunities.

Your textbook (p. 344) reports that in 1990, more than 57% of Navajo families living on the reservation lived below the poverty level. More than 25 years later this number has only slightly improved; today, some 43% live under the poverty level.

Today, the economic mainstay of most Navajo on the reservation is sheep and cattle raising and crafts (particularly silver-working and rug weaving). Despite its remoteness and lack of access to wage-sector jobs, the Navajo reservation does have abundant natural resources (particularly uranium and coal) that are sought after by mining companies.

However, because of the environmental damage and health hazards associated with mining, development of mining activities is a source of great controversy among the Navajo. Radioactive waste from uranium mining, conducted from the 1940s to the 1980s, has left behind a damaging legacy.

Coal mining—while providing much needed jobs and income-- has also been problematic; in 2005 one of the largest strip mines on the reservation was shut down for emission violations.

Although Navajo was slow (compared to many other Native American tribes) to authorize gaming on their reservation, since 2004 the tribe has opened four casinos. These casinos have created more than 1,500 jobs, of which 90 percent are held by Navajo. Additionally, in recent years the tribe has begun to explore the feasibility of operating alternative energy enterprises such as solar power plants and wind farms.

Click on next page to continue.

Practice Quiz #10