The Apache

Module 11

There are seven recognized Southern Athapaskan tribes. Of these, we have already discussed one (the Navajo), and two (the Kiowa-Apache and the Lipan Apache, who lived in what is now the Texas panhandle and central Texas) will not be covered in this class because they are located outside the Southwestern geographical area. The remaining four Apachean groups will be covered in this module; these are the Jicarilla Apache, the Mescalero Apache, the Chiricahua Apache, and the Western Apache. These groups share broadly similar cultural patterns but differ in terms of specific adaptations and elements borrowed from other cultures. The Apache are probably best known for their prowess in battle and their skill in eluding capture. Led by such men as Cochise and Geronimo, they were the last of the Native Americans to be subdued and moved to reservations.

There are seven recognized Southern Athapaskan tribes. Of these, we have already discussed one (the Navajo), and two (the Kiowa-Apache and the Lipan Apache, who lived in what is now the Texas panhandle and central Texas) will not be covered in this class because they are located outside the Southwestern geographical area. The remaining four Apachean groups will be covered in this module; these are the Jicarilla Apache, the Mescalero Apache, the Chiricahua Apache, and the Western Apache. These groups share broadly similar cultural patterns but differ in terms of specific adaptations and elements borrowed from other cultures. The Apache are probably best known for their prowess in battle and their skill in eluding capture. Led by such men as Cochise and Geronimo, they were the last of the Native Americans to be subdued and moved to reservations.

Required Reading

- Griffin-Pierce Chapter 9

- Film- Geronimo: We Shall Remain. 60 minutes (streams through the library)

Learning Objects

- Students will be able to name the four different Apache "tribes" discussed here, describe their major differences, and explain why those differences existed

- Students will be able to describe the Apache worldview and ceremonial practices

- Students will be able to describe the major historical events that affected the Apache

- Students will be able to explain the importance of raiding and warfare to the Apache people

- Students will be able to define major terms and concepts relevant to understanding the Apache culture

Major Concepts and Terms

- Tipi

- Wickiup

- Monster Slayer

- White Painted Woman

- Priestcraft

- Shamanism

- Gaan

- Crown Dancers

- Sunrise Ceremony

- Cochise

- Apache Wars

- Geronimo

Click on next page to continue.

Map of Origins and Subgroups

Instructions: Using the slide button on the lower right hand corner, toggle between Apache Past Territories and Apache Modern Reservtions pages. You can also click on the tabs on the top of the map to learn more. The selected page is highlighted in blue.

If you are having trouble with viewing this map, click on this link to view - https://courses.online.unlv.edu/courses/ANTH/ANTH400C/apache-map/

Click on next page to continue.

Origins and Subgroups

|

The Apache share the same origins as the Navajo. Sometime between about 800-1000 A.D., their shared ancestors left Canada and began the long migration southward. Linguistic evidence suggests that at about 1300 A.D., before the Apachean ancestors had arrived in the Southwest, the group that would become the Kiowa-Apache had already split off from the others and moved eastward. Shortly after the remaining Apacheans arrived in northern New Mexico around 1400 A.D. the remaining groups began to diverge linguistically as well.

Like their cousins the Navajo, the Apache were a highly adaptable people who readily modified their lifeways to meet the needs of the environments in which they lived. Cultural differences between Apache subgroups largely reflect differing adaptations to the territories occupied by the groups. Other differences reflect variations in their interactions with other tribes.

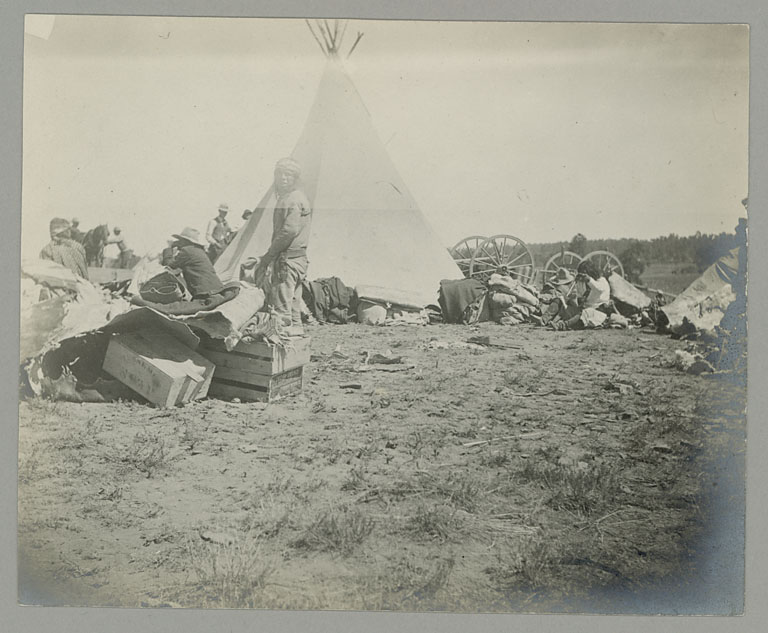

Of the four tribes discussed here, the Jicarilla experienced the greatest contact and influence from Plains tribes (as did the two tribes not discussed here, the Lipan and Kiowa-Apache). Like the Plains Indians, they hunted buffalo, emphasized raiding and warfare, and lived in portable tipis. Although they also farmed, hunting and gathering of wild plants was their economic mainstay. The Jicarilla were the most nomadic of the Apache groups considered here.

|

Jicarilla Apache tipi, 1898. The Jicarilla adopted the tipi—which was adapted to their mobile lifestyle-- from the Plains Indians.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/apache/02076800.jpg

|

|

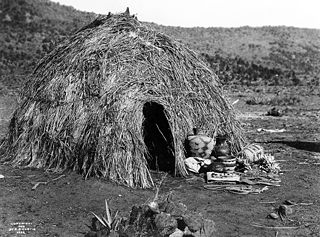

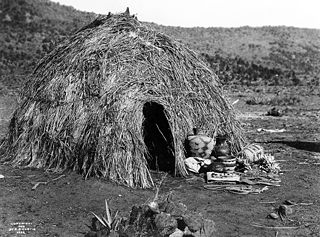

Apache wickiup, 1903. The semi-sedentary Western Apache constructed wickiups to live in, much like the early hogans built by the Navajo.

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apache_Wickiup,_Edward_Curtis,_1903.jpg

|

The Western Apache had the greatest contact with the Puebloan people, and as a result were the group most heavily influenced by that culture. This group had the greatest reliance of any of the groups on farming, though agriculture never superseded hunting and gathering in importance.

The Western Apache were semisedentary, living in wickiups (or brush structures) near their agricultural fields for a portion of the year. During the remainder of the year they moved about to take advantage of the various wild resources that could be collected.

|

|

The Mescalero and Chiricahua were the least influenced by the Plains and Puebloan cultures. These tribes were highly nomadic and relied on hunting and gathering for their subsistence. Although limited farming was practiced by some Mescalero and Chiricahua, it was not enough to significantly affect their food economy or lifestyle.

Today, the Apache live on six reservations in New Mexico and Arizona; one of which (Camp Verde) they share with the Yavapai. Numerous Chiricahua Apache also live near Fort Sill, Oklahoma on land that was allotted to them after the end of the Apache Wars.

|

Click on next page to continue.

Social and Political Organization

|

The extended family was the basic Apache social unit. Except for the Western Apache who were matrilocal (like the Navajo and Puebloan groups by whom they were strongly influenced), post marital residence patterns were generally patrilocal or bilocal. Several extended families would join together to form a local group that would live together during part of the year and join together for various ceremonies and other activities.

The composition of these local groups tended to be quite flexible, with people freely moving back and forth between different groups depending on their personal preference. Above the level of these local groups was the band, which was the largest political unit with which the Apache identified.

These bands, in turn, were grouped into the larger entities that are commonly referred to as tribes - that is, the Jicarilla, Western Apache, Mescalero, and Chiricahua groups.

However, it should be stressed that the use of the term "tribes" is really a misnomer—while the Apache recognized distinctions between these groups, they never really had a sense of tribal consciousness and (with the exception of Cochise's short tenure among the Chiricahua) never were politically unified at these socalled tribal levels.

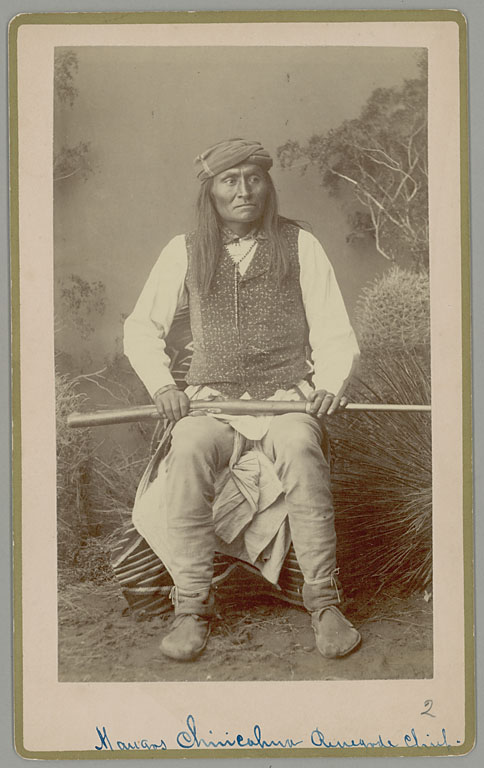

Each local group and band had a leader who acquired the position through respect for his personal traits. These respected men led by persuasion but could not coerce others to follow his lead.

|

|

|

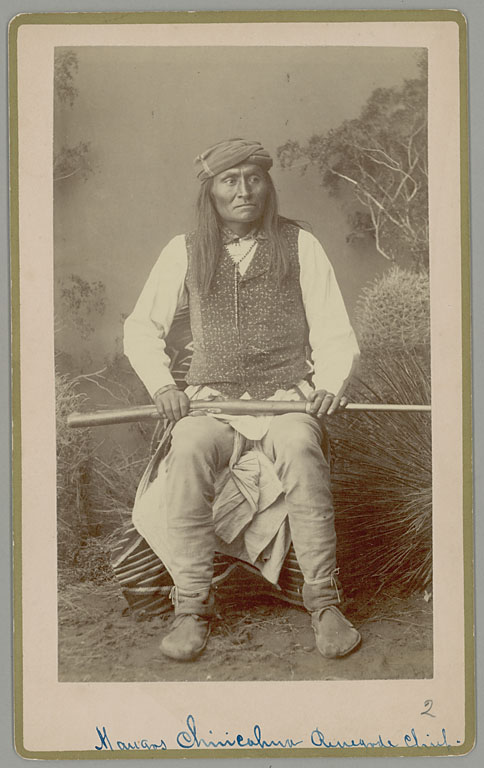

Chief Mangas of the Mimbrenos band of the Chiricahua, 1886. In the late 19th century the U.S. government often signed treaties with such "chiefs," not understanding that the leader had only limited influence, and that even that influence extended over only a small proportion of the tribe.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/apache/02038800.jpg

|

Click on next page to continue.

Subsistence and Material Culture

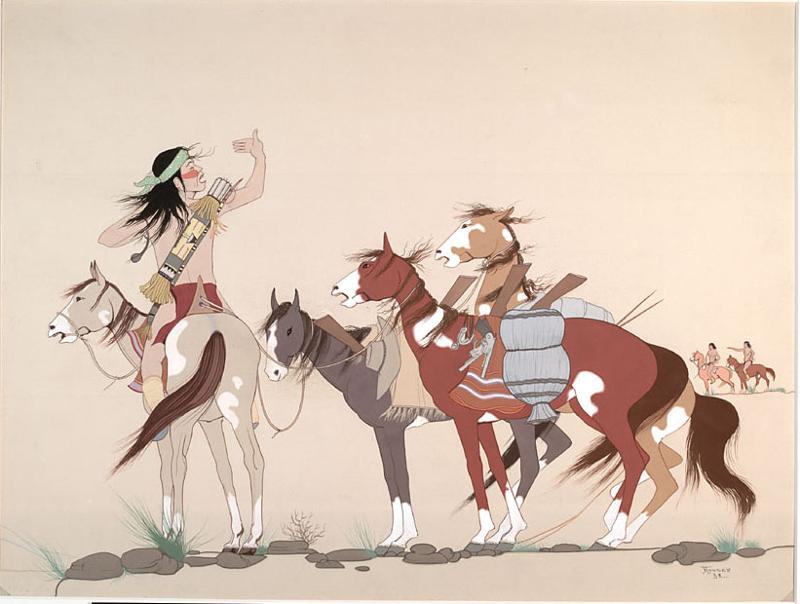

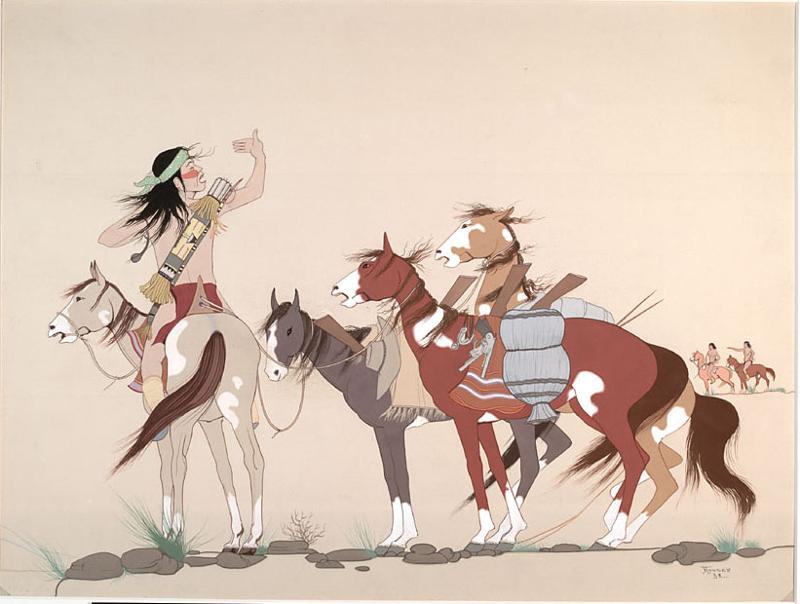

All Apache were primarily hunters and gatherers, though some groups (notably the Western Apache) supplemented gathered food resources with agriculture and the Plains influenced groups, including the Jicarilla, emphasized bison hunting. All groups were either nomadic (moving every few days) or seminomadic (moving several times during the course of a year). Raiding was an important economic activity that gained in prominence after the Spaniards introduced horses into the region. Raids were an important avenue to power for Apache men, and a boy's first raid was considered his initiation into manhood.

Although the seasonal cycle varied by group, most followed something like that of the Mescalero. In early spring, the Mescalero moved with their extended family groups to areas where they could plant their corn, beans, and squash. They did not stay to tend the crops, but in late spring moved again to areas where agave could be collected and roasted. In early summer they collected cactus fruit, in the early fall they collected mesquite beans, and by mid fall they returned to their farm plots to retrieve whatever crops might be available for harvesting. Winter was spent in large base camps and was a time for raiding.

'After the Raid.' Painting by Allan C. Houser, 1938.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/74-7/08795000.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

Religion and World View

The Apache share a common worldview with one another and with the Navajo, reflecting their collective Athapaskan origins. These include a fear of ghosts and of the recently dead, the notion that power can be granted to individuals by nonhuman helpers, and the belief that disease is caused by contact with certain animals. All of these beliefs are also found among northern Athapaskan groups.

Also shared by most of the groups is an origin story in which they came into being when supernatural beings emerged on the earth from the underworld. In the early days of existence, various monsters lived on the earth who threatened the lives of humans. However, the earth was made safe when the deity Monster Slayer killed these monsters. Monster Slayer is the son of White Painted Woman, the first woman and the most important of the Apache deity.

Drawing of Apache Crown Dancer by Acee Blue Eagle.

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/74-7/08778200.jpg

Click on next page to continue.

Ceremonies

|

Apache rituals combine priestcraft (in which power derives from the practice of learned, communal ceremonies) with shamanism (in which power derives from solitary visions and activities). The Apache believe that the supernatural power that pervades the universe can be acquired through dreams or supernatural means, but that the rites that are bestowed from this power can be taught to others. Ceremonies are conducted for a variety of purposes, including to protect against illness, to improve luck in hunting, or to assure a prosperous life. Rituals are based on the concept of reciprocity, in which it is believed that specific songs, prayers and offerings can be used to attract the gaan (or gaa'he, as they are referred to among some Apache groups), the supernatural beings that live in mountains and caves.

These mountain spirits will then be obligated to reciprocate by bestowing their power to the shaman or patient. Like the Navajo, the Apache make use of singers and sandpaintings to invoke supernatural blessings. Some ceremonies involve the participation of Crown Dancers (also known as gaan dancers) who wear masks and large headdresses during dances that can last through the night. Like the sandpaintings and songs, these dances are believed to entice the gaan spirits to come. During the dances the Crown Dancers are believed to "become" the mountain spirits in much the same way that the Hopi kachina dancers "become" the kachina while they are dancing.

Apache Crown Dancers, 1889

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02563b.jpg

|

The most important of the Apache rituals is the girls puberty ritual known as the Sunrise Ceremony. This ceremony lasts four days, during which time the girl is infused with White Painted Woman's powers of renewal and rebirth. As in the Navajo kinaalda ceremony, during the Sunrise Ceremony the girl is expected to be molded by an older woman into a woman that possesses the admirable traits of White Painted Woman. Because these ceremonies involve the hosting of large numbers of people and the serving of feasts, they were (and still are) expensive to host. In early historic times, raiding provided a man with the resources needed to host his daughter's Sunrise Ceremony. Today, not every Apache girl has this ceremony, both because not everyone can afford it and because not everyone wishes to do so. To offset the costs associated with the ceremony, it is common today for a community to host one large Sunrise Ceremony per year for all girls that have come of age that year.

Hide painting made by Cochise's son Naiche, ca. 1900, depicting an Apache girl's puberty ceremony

Source - By Uyvsdi (Own work) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

|

Click on next page to continue.

History

|

The history of the Apache people is a history of conflict. When the Spaniards arrived in Arizona and New Mexico, Apache raiding aimed at neighboring Indian tribes was a commonplace occurrence. With the introduction of the horse the Apache easily expanded their raids to include Spanish settlements. Raiding led to retribution, which quickly escalated into a cycle of conflict and warfare that only intensified when the Apache territory came under Mexican control.

When the Americans acquired the Apache homeland in the 1850s, they inherited this cycle of conflict. Determined to end the bloodshed, the federal government initiated a campaign to relocate all Apache to reservations. This was a frustrating process for the U.S. Army, as peace treaties signed by various headmen would be broken promptly by other Apache. The problem was created by a lack of understanding on the part of Americans of Apache social organization; Americans failed to appreciate that most headman could speak for, at most, only a few dozen Apache. Regardless, by 1868 nearly all of the Apache had been subdued and relocated except the Chiricahua.

The Chiricahua resistance was initially headed by Cochise, who became angered when his uncle Mangas Coloradas was tortured and murdered in 1863 after being convinced to meet with the U.S. Army for peace talks. Over the next few years, Cochise was to become a widely respected leader, eventually gaining the following of all of the Chiricahua bands. Cochise thus was the first and (until modern times) the only Apache leader to unify the entire tribe and to gain leadership over all of its people. Cochise successfully waged war against the U.S. until 1872, when he was persuaded to surrender in exchange for a Chiricahua Apache reservation in Arizona. Conditions were not good on the reservation and most of the Apache were unhappy, but under the persuasive leadership of Cochise they agreed to remain there.

|

Cochise's Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains, southern Arizona. Cochise was able to hide out in these mountains until 1872 to avoid capture.

Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Cochise_Stronghold#/media/File:Owl_rock_-_Cochise_Stronghold_East.jpg

|

|

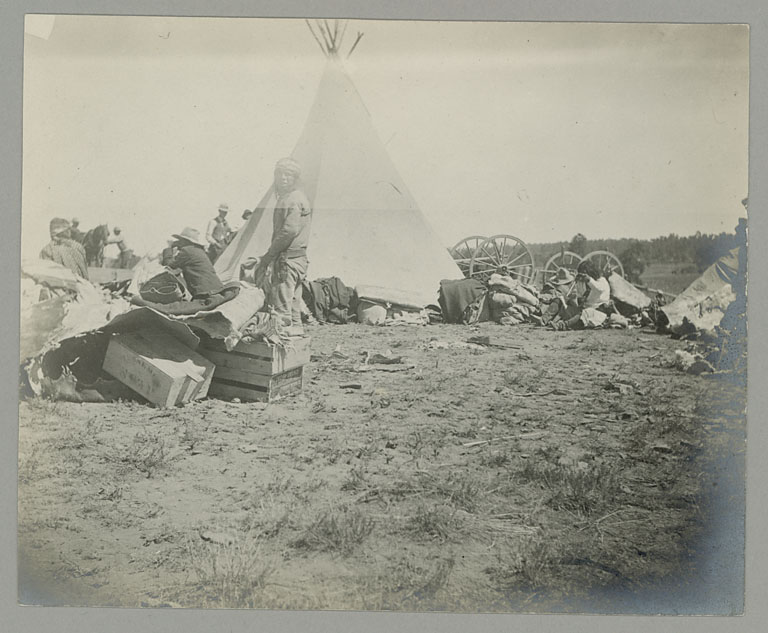

Unfortunately for both the U.S. Army which oversaw the reservation and for the Chiricahua Apache, Cochise died in 1874. Upon his death, tensions on the reservation increased which led the federal government to relocate the Chiricahua to the San Carlos reservation, which at that time housed primarily members of the Western Apache tribe. Conditions on that reservation were even worse, and in 1881 a group of Chiricahua headed by Geronimo escaped.

This marked the beginning of the Apache Wars, which would be the last of the Indian wars to be fought in our country. It was also one of the bloodiest, with Geronimo soon earning the reputation of a vicious killer who would kill anyone, including women and children, found in his path. Inflamed by lurid newspaper accounts, most Americans at the time feared and hated him.

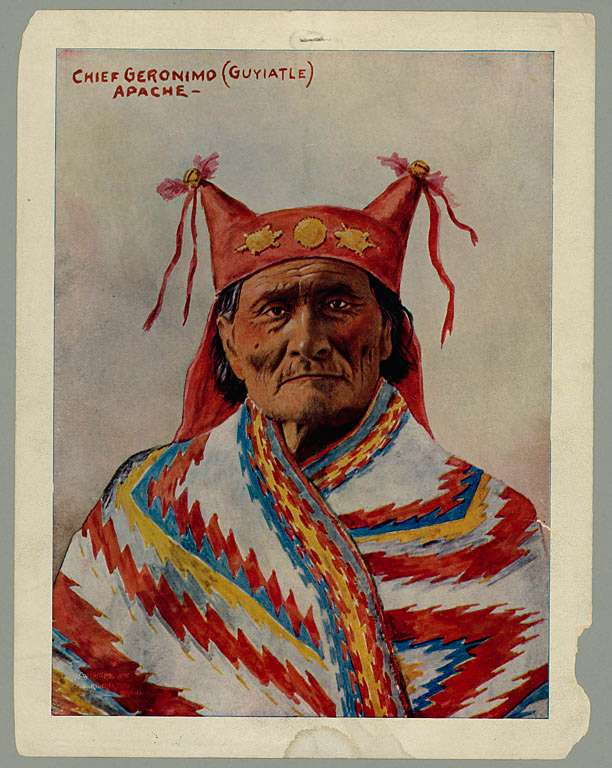

The Apache themselves viewed him with mixed emotions; while they respected him for his military prowess and fearlessness, he was considered too hotheaded to be accepted as chief. Thus, Geronimo was never a chief but instead was considered a military leader.

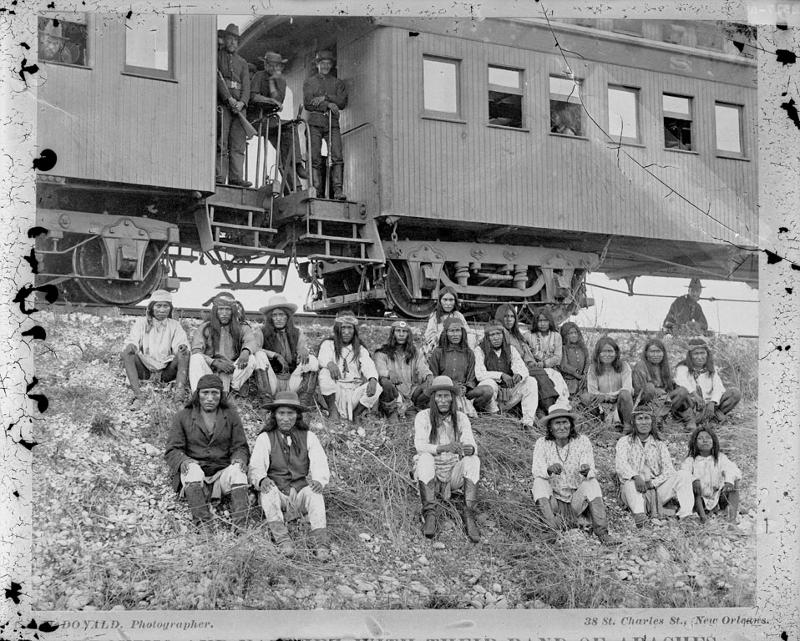

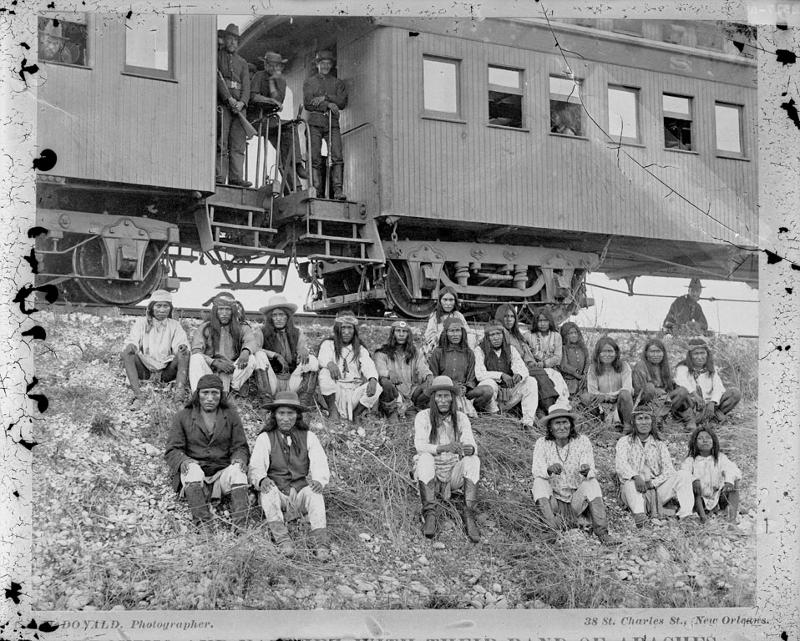

Geronimo became the most hunted man in the country, with his small band of 39 fugitives ultimately being pursued by some 5000 American troops and 3000 Mexican troops. To avoid capture the fugitives found themselves constantly on the move. With the help of some Chiricahua scouts, Geronimo's band finally was found and convinced to surrender on September 8, 1886. Geronimo's band—along with all other Chiricahua, including those that had remained on the reservation and those that had helped the Army find Geronimo—were classified as prisoners and sent to facilities located in Florida and Alabama where nearly one quarter of them died.

In 1894 they were relocated once again to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where conditions improved. It wasn't until 1913, however, that they were freed as prisoners of war. At that point they were given the choice of remaining near Fort Sill or moving to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico. Most moved to New Mexico but a few elected to remain near Fort Sill, where their descendants today are known as the "Fort Sill Apache."

|

Geronimo and his followers being taken as prisoners to Florida after their surrender, 1886

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02517a.jpg

|

|

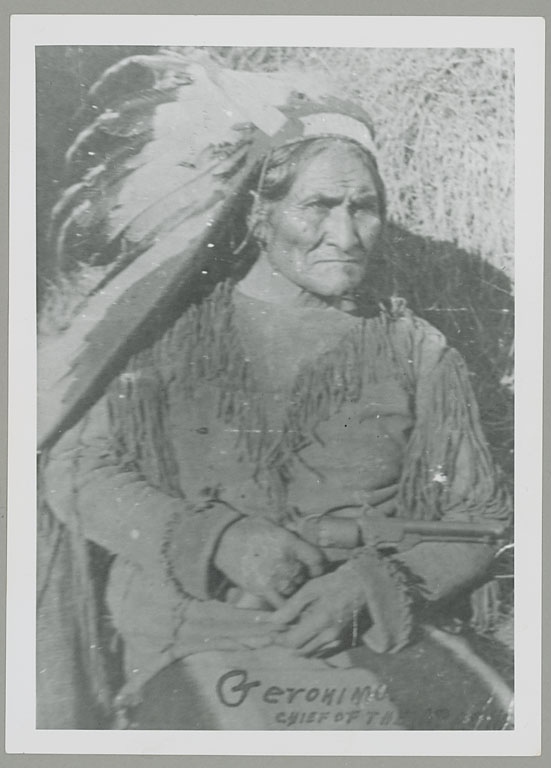

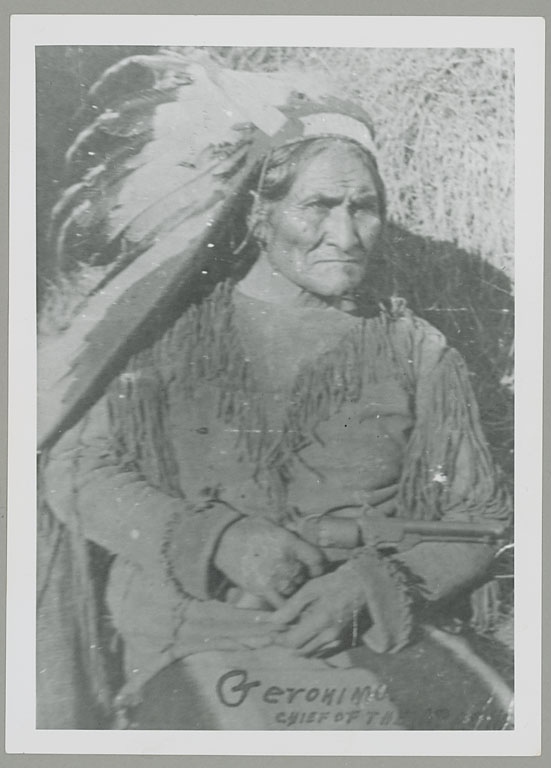

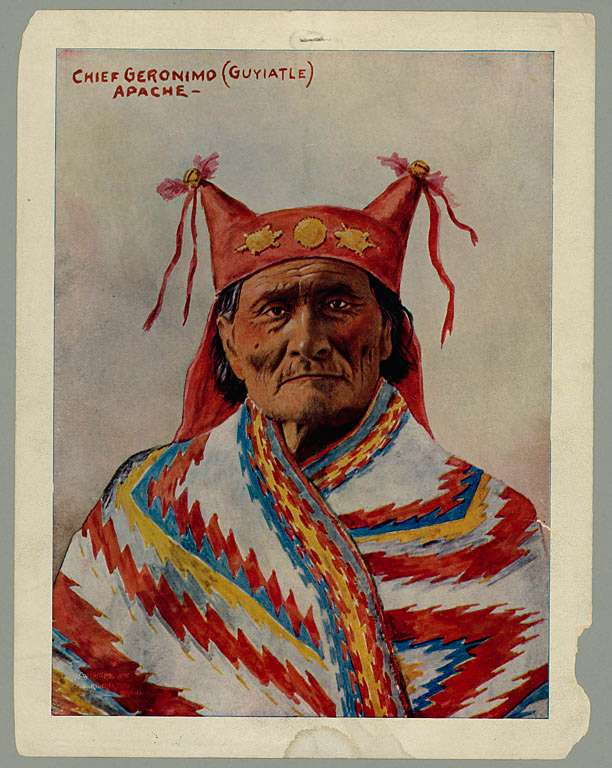

Geronimo, once the most feared and hated man in American, became transformed in the American imagination into a folk hero.

Although still technically a prisoner, from the late 1890s until his death in 1909, he was allowed by the federal government to make public appearances where he would sell photographs of himself. However, he was never granted his lifelong wish to be able to return to his homeland in Arizona.

Photograph of Geronimo, taken at a fair in 1905. In his later years, Geronimo was considered something of a folk hero and appeared at fairs and Old West shows where he sold photographs of himself and souvenirs

Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/apache/02021900.jpg

|

Today, the fascination with Geronimo continues. Rumors persist that his bones were dug up by pranksters (including Prescott Bush, father of the first President George Bush) in 1918 and given to the secret Skull and Bones society associated with Yale University.

The Apache sued for the return of these remains in 2009 but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence in 2010.

The same year that this lawsuit was filed, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring Geronimo for his "extraordinary bravery, and his commitment to the defense of his homeland, his people, and the Apache ways of life." And, in 2011, Geronimo's name served as the code name for the operation to get Osama Bin Laden.

|

|

Practice Quiz #11

|

There are seven recognized Southern Athapaskan tribes. Of these, we have already discussed one (the Navajo), and two (the Kiowa-Apache and the Lipan Apache, who lived in what is now the Texas panhandle and central Texas) will not be covered in this class because they are located outside the Southwestern geographical area. The remaining four Apachean groups will be covered in this module; these are the Jicarilla Apache, the Mescalero Apache, the Chiricahua Apache, and the Western Apache. These groups share broadly similar cultural patterns but differ in terms of specific adaptations and elements borrowed from other cultures. The Apache are probably best known for their prowess in battle and their skill in eluding capture. Led by such men as Cochise and Geronimo, they were the last of the Native Americans to be subdued and moved to reservations.

There are seven recognized Southern Athapaskan tribes. Of these, we have already discussed one (the Navajo), and two (the Kiowa-Apache and the Lipan Apache, who lived in what is now the Texas panhandle and central Texas) will not be covered in this class because they are located outside the Southwestern geographical area. The remaining four Apachean groups will be covered in this module; these are the Jicarilla Apache, the Mescalero Apache, the Chiricahua Apache, and the Western Apache. These groups share broadly similar cultural patterns but differ in terms of specific adaptations and elements borrowed from other cultures. The Apache are probably best known for their prowess in battle and their skill in eluding capture. Led by such men as Cochise and Geronimo, they were the last of the Native Americans to be subdued and moved to reservations.