Japan | Study Guide Images

View the study guide images for this region. You can access each study guide image and its information by clicking on the corresponding tab. Feel free to rearrange the tabs by clicking and dragging them over one another. Click on the menu icon to reset the accordion. Hovering over the menu icon allows you to navigate to a study guide image you wish to see.

Flame-Style Vessel

Flame-Style Vessel: Earthenware, 2 ' high.

found in Nigata Prefecture, Japan

Middle Jomon Period

10,500 BCE–300 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. "Illustrated here is a so-called flame-style vessel, named for the shapes projecting from the sculptured rim of its characteristically flaring cylindrical body. The potter formed the body of the vessel by hand and then applied clay coils in straight lines and wave patterns. The resulting intricately modeled surface is the hallmark of Jomon pottery. Jomon vessels contrast strikingly with China’s most celebrated Neolithic earthenwares, which emphasize basic ceramic form and painted decoration."

The Jomon Period (before 10,000 – c. 300 BCE) in Japan coincides in part with a Paleolithic and Neolithic level of technical culture. Agriculture, which is a feature of the Neolithic period in other parts of the world, is undeveloped. People were still primarily hunter-gathers. Low-fired pottery (ceramics) is found from the earliest period. However, in the Middle Jomon, large jars with elaborately decorated rims, became the norm. These gradually died out in the Late and Later Jomon period and eventually disappeared, only to be discovered in the late 19th Century by Edward S. Morse, an American zoologist, who was excavating shell mounds in Tokyo. The pottery shards he found were decorated with rope-marked designs, jomon in Japanese. Thus Jomon became the name for the entire era.

Form

The forms are unique to Japan. Deep jars with either flat or pointed bottoms, whose diameter increases with its height. The rims are often embellished with large three-dimensional extension into space, that resemble organic forms in nature. What do they look like to you? Approaches sculpture.

Style

Abstract. Fanciful. Playful?

Meaning

What do you think is the meaning of the designs?

Context

Evidence suggests that these ceramic forms were at least partly utilitarian, and used for cooking. The Jomon people

lived on a diet heavily supplemented by marine animals, fish, and shellfish. Broken pottery was thrown on the rubbish

heap with empty shells. Figurines appear in the Middle-Late Jomon period.

Jomon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.)

Dotaku

Dotaku:

Bronze, 1' 4 ⅞" high

found in Kagawa Prefecture, Japan

late Yayoi period

300 BCE–300 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. "The bronze bells, which are oval in section and range in height from 5 inches to more than 4 feet, were treasured ceremonial objects. Cast in clay molds, these bronzes generally featured raised geometric decoration presented in bands or blocks. On some of the hundreds of surviving dotaku, including the medium-size example illustrated here, the ornamentation consists of simple line drawings of people, animals, and boats, often in scenes of hunting and fishing or agricultural activities."

Some time around 300 BCE a wave of immigration inundated western Japan pushing the Jomon peoples east and northeast.

These immigrants from the mainland (China, Korea) were technologically advanced, possessing bronze technology and

sophisticated agriculture; they brought rice and wet-field rice-growing systems to Japan for the first time. The Yayoi

era represents an immense cultural shift. The name of the Yayoi period derives from a neighborhood in Tokyo where

the culture was first identified. Like the Jomon period, Buddhism has not yet been introduced to Japan; the native

indigenous religious practice called Shinto, often likened to shamanism and possibly dating back to

the Jomon period, was already well developed.

Shinto

Form

The form, a dotaku (bronze bell), is directly inspired by Chinese bronze bells, which were used as musical instruments

in Chinese court culture from the Shang through the Zhou Dynasties. Chinese bronze mirrors were also brought to Japan

at this time.

Bells

However, unlike the Chinese bells, the Yayoi bells do not appear to have been used in the same way, but for ceremonial

rites connected to agriculture, possibly attached to wooden poles and stood in fields.

Dotaku (Ritual Bronze Bells) and the Yayoi Period

Style

Just as the form betrays its reliance on imported mainland models; so does the style: symmetry, rational organization of décor, geometric designs, and most important of all, narrative subjects crudely depicted in stick figures.

Meaning

Is connected to function. The narrative scenes reflect human activities and depict various animals, perhaps used in sacrifice.

Context

Used in public ritual in a highly stratified, agricultural society.

Honden of the Ise Jingu

Honden of the Ise Jingu:

Wood with thatch roof

found in Ise, Mie Prefecture, Japan

Kofun period or later

300 CE – 552 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Purification concepts are the basis for the cyclical rebuilding of the sanctuaries at grand shrines. The buildings of the inner shrine at Ise, for example, have been rebuilt every 20 years for more than a millennium, with few interruptions. Rebuilding rids the sacred site of physical and spiritual impurities that otherwise might accumulate. During reconstruction, the old shrine remains standing until carpenters build an exact duplicate next to it. In this way, the Japanese have preserved ancient forms with great precision. "

The Kofun (Old Tomb Period, or Tumulus Period) represents yet another major cultural transformation in Japan. While Buddhism will not be known until the late Kofun period, the period is marked by several new cultural forms, again brought by peoples settling in Japan from the mainland, Korea most likely - especially the construction of large tomb mounds for rulers and nobility, as well as previously unknown horse-riding culture. Ise Shrine is the most import early pre-Buddhist architectural form to survive in Japan. The Shrine to the Sun Goddess is the inner of two shrines at Ise.

Form

The architectural form of the Grand Shrine to the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, is derived from grain storehouses of the Yayoi and Kofun eras. The Yayoi features suggest an origin in south China or Southeast Asia where flooding is perennial: a platform floor, raised high from the ground on tall pillars to keep out water, pests, and thieves. Raised platform architecture continues to represent the Japanese tradition in contrast to later Chinese architectural forms introduced with Buddhism at the end of the Kofun era. The Kofun-dated features are the large overhanging roof of thatch, the large logs weighting down the ridgepole, and the antennae like forms extending from the eaves. Another form associated with the sacred places of Shinto is the torii (bird rest) gateway.

Style

Timber, post and lintel construction, supporting pillars are sunk into the ground. Traditional Japanese architectural prototype. The style is tongue and groove; no nails are used; all material is natural; no paint or lacquer. All architectural parts are formed and put together like a puzzle. Woods are aromatic and precious. All is the work of human labor with the exception of transportation, no machines. It is labor of spiritual devotion.

Meaning

The main hall is where the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, the progenitor of the Japanese Imperial line, comes to visit. As spirit she has no body and goes wherever she likes, but this is where she will come to be appealed to, or to receive news and visits from the Imperial Family. According to the Japanese oral and later written histories, she chose this location herself for its seclusion and beauty. The shrine has traditionally been rebuilt in grand rituals every 20 years.

Context

Shinto shrine. During this time period Japanese society is gradually coming under the rule of a single family

or clan who assume the role of emperor and imperial family; this group traces its origins to the Sun Goddess, a connection

that has been maintained up to the present time and was particularly symbolic during Japan’s period of modernization

and development as a nation state in the 19th and 20th Century.

BEGIN Japanology - Ise Jingu

Golden Crown

Golden Crown:

Gold-and-jade crown

found in the Silla tomb Hwangnam-dong, South Korea

Three Kingdoms Period

57 BCE – 688 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Tombs of the Silla kingdom have yielded spectacular artifacts representative of the wealth and power of its rulers. Finds in the region of Gyeongju, the Silla capital, justify the city’s ancient name—Kumsong (City of Gold). The gold-and-jade crown from the Cheonmachong (Heavenly Horse) tomb at Hwangnam-dong, near Gyeongju, dated to the fifth or sixth century, also attests to the high quality of artisanship among Silla artists. The metalsmith who fashioned this crown’s major elements—the band and the uprights—as well as the myriad spangles adorning them, cut the forms from sheet gold and embossed the edges. Gold rivets and wires secure the whole, as do the comma-shaped pieces of jade further embellishing the crown. Archaeologists interpret the uprights as stylized tree and antler forms believed to symbolize life and supernatural power. The Cheonmachong crown is one of several magnificent surviving Silla crowns, but none of them has a Chinese counterpart, although the technique of working sheet gold may have come to Korea from northeastern China. "

The Three Kingdoms Period in Korea and the Kofun Period in Japan are closely related, although the exact nature of the relationship is disputed. Several gold crowns have been discovered in Korean tumuli (tomb mounds like those found in Japan). Although no gold crowns like these have been discovered in Japan, there are many similar gilt-bronze small crowns, pieces of armor, and horse equipment that show close similarities between Korea and Japan at this time.

Form

The crown is meant to sit on the head of the ruler, encircling the forehead. Tall “tree of life” shapes, associated with Shamanism, rise from the lower circle; these tall forms are decorated with small green jade carvings in the shape of a tooth or claw, and small flat circles of gold; and hanging from the circle of gold are numerous trailing chains, similarly decorated. When worn, the thin beaten gold forms would sway and the jade jewels and gold “coins” would make a beautiful musical sound. In Japan, the small curved jade jewels are common elements of decoration and are often associated with the Imperial Family.

Style

Symbolic, elegant, exquisite craftsmanship

Meaning

Possibly indicating that the ruler has the power of a shaman. In Japanese Shinto, priests and priestesses are thought to have such connections with the spirit world.

Context

Evidence of the close cultural and possibly political relationship between Korea and Japan at this time, and more widely, to the “international” practice of Shamanism across Northeast-Northwest Eurasia.

Shaka Triad

Shaka Triad:

Bronze, 2' 10" high

found in Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture, Japan

Asuka period

552 CE – 645 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The central figure in the triad is Shaka, seated with his right hand raised in the abhaya mudra (fear-not gesture). The flaming mandorla that forms a backdrop to the historical Buddha incorporates small figures of other Buddhas. The sculptor was a descendant of a Chinese immigrant, and the Horyuji Shaka triad reflects the style of the early to mid-sixth century in China and Korea, a style that featured elongated heads and elegant drapery folds forming gravity-defying, waterfall-like swirls. "

During the Asuka Period Japan suddenly adopted Buddhism. It came as a gift from Korea. The gift included Korean artisans, craftsmen, architects, builders, bronze-casters, and models of Buddhist art; the craftsmen set to work immediately to built temples and cast images. The practice of tomb building gradually receded as the Buddhist practice of cremation became widespread. This is not only one of the most important early Japanese Buddhist images, it is an historical artifact intimately related to the Imperial Family through the information contained in the long Chinese inscription on the back of the halo, which tells its story.

Form

The form is the standard iconography of a seated Buddha flanked by two Bodhisattvas. Do you recognize the mudras and the other elements of iconography that we studied in Indian and Chinese art?

Style

The style is Chinese, the style of Buddhist art practiced 100 years earlier during the Wei Dynasty. Compare this with the gilt-bronze image of Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna, dated to 518 CE. (Chapter 16-14). What similarities of figure and drapery do you notice?

Meaning

This image has three meanings.

- it represents the Buddha Shaka (the Japanese term for Shakyamuni) interacting with the worshipper;

- it is an offering made by the Imperial Family to obtain healing and good karma for Prince Shotoku, who is seriously ill;

- its body is a symbolic, mathematical representation of Price Shotoku, and the face a portrait.

Context

Buddhism was introduced to Japan, over the objection of the Shinto priests, on the basis of its ability to protect the nation;

Buddhism was believed to have healing and miraculous powers for this life or the next that could be accessed through

sacrifice and devotion.

Shaka Triad and Kōmokuten

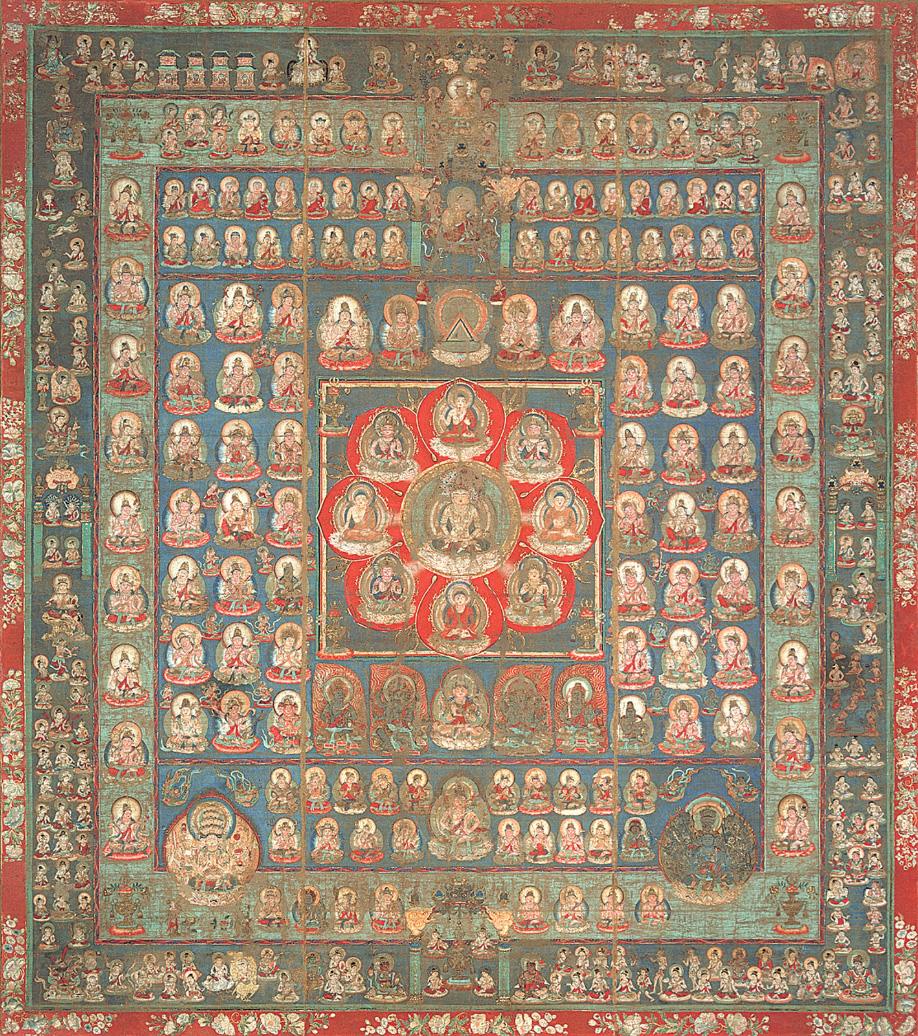

Taizokai

Taizokai:

Hanging scroll, color on silk, 6' x 5' ⅝"

Kyoto, Japan

Early Heian period

794 CE – 1185 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The central motif in the Womb World is the lotus of compassion. In the Diamond World, it is the diamond scepter of wisdom. The Womb World is composed of 12 zones, each representing one of the various dimensions of Buddha nature (for example, universal knowledge, wisdom, achievement, and purity). The Taizokai mandara illustrated here is among the oldest and best preserved in Japan. "

This almost 6 x 6 ft.sq. painting is one of a pair of mandara (mandala in Sanskrit)

that hang on either side of the Buddhist altar in the Toji Temple, a temple of the esoteric Shingon (True Word) Sect.

The esoteric Buddhist sects were introduced to Japan in the early 9th Century, by Japanese monks who went

to China to study. The origin of the esoteric Buddhist sects, which absorbed many features from Hinduism, is India;

today Nepalese and Tibetan Buddhism are further examples of esoteric Buddhist practices. This mandara is

a rare example of early esoteric Buddhist iconography in Japan. The Buddha of the esoteric sects is known as Mahavairocana (Dainichi, or “the great sun”) who is and exists at the center of the universe. To distinguish Dainichi

from other Buddhas a new iconography was developed, combining mudra and postures unique to the Buddha with some of

the features of a bodhisattva: long hair, crown, jewelry, etc. The famous monk, Kukai, is credited with introducing

Shingon Buddhism to Japan. He is also credited with inventing the Japanese syllabary (kana – borrowed

characters) that all allowed for writing in vernacular Japanese for the first time.

Kukai

Form

A mandala/mandara is a conceptual and symbolic diagram of the Buddhist cosmos. The Taizokai (Japanese for ‘womb world”) symbolizes the source of the universe as a womb out of which all manifestations are born. The iconography of the Womb World mandala features a lotus in the center with the Buddha Dainichi occupying the center of the lotus. Here he sits in the meditation (lotus seat) posture and holds the meditation mudra.

Style

The painting style is early Heian: the faces of the Buddha’s are sweet and very round, and the heads large.

Meaning

The Womb World mandala represents the various manifestations of the Buddha essence. As such it possesses potential spiritual

power that can be accessed by the worshipper in his/her search for enlightenment. All form emerges from the Buddha

essence. For the worshipper the mandara can be an object of meditation; or the worshipper can choose

one of these manifestations of the Buddha as the focus of their practice.

Quick Guide to Japan’s Ryōkai (Two Worlds) Mandala

Context

The Heian era is a time when Japan gradually begins to free itself from Chinese and/or Korean models and develop a unique and highly sophisticated culture of its own Kukai’s emphasis on the necessity of Beauty to express Buddhist truths, inspired and supported a growing taste for aesthetics in all aspects of life.

Genji Visits Murasaki

Genji Visits Murasakis:

Handscroll, ink and colors on paper, 8'⅝' high

found in Japanese imperial court

Heian period

794 CE –1185 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Tale of Genji tells of the life and loves of Prince Genji and, after his death, of his heirs. The novel and much of Japanese literature consistently display sensitivity to the sadness inherent in the transience of love and life. These human sentiments are often intertwined with the seasonality of nature. These concrete but evocative images frequently appear in paintings, such as the illustrated scrolls of Tale of Genji. "

By the middle Heian period, the Fujiwara Period, native Japanese aesthetics were fully developed, especially

in secular painting and Buddhist sculpture. The imperial court and aristocrats like the powerful Fujiwara clan were

obsessed with the arts and with cultivating individual talents in handwriting (calligraphy), poetry, dance, music,

and, for men, facility in the Chinese classics, and the ball game. While there were professional artists who created

masterpieces of luxury art goods, like screen and wall paintings, paper for calligraphy, textile designs, etc., talented

amateurs among the aristocratic class were even more highly respected. The famous of these was a woman and a court

lady, Murasaki Shikibu. While at court she wrote serially a long multiple-chapter story about a handsome prince

and his life and loves, The Tale of Genji, that has been hailed as the world’s first true novel. This

is one illustration of many that survive from a 12th century version of the tale; it is the earliest extant

example of what became a popular form of court narrative painting.

Murasaki Shikibu (Ritual Bronze Bells) and the Yayoi Period

Form

Emaki/emaki-mono, Hand-scroll: horizontal scenes separated by calligraphic texts, in continuous alternation. Currently, the hand-scroll has been cut up into sections of painting and text and preserved in individual boxes, in different museum collections. Originally there were 20 scrolls in the set, each with 2-4 illustrations.

Style

naïve: simple mask like faces all alike for both men and women; birds-eye perspective with the roof removed. Quiet, interior scenes, little movement. Thick opaque mineral colors applied over under-drawings; hair, and black lines redrawn in lacquer black.

Meaning

Narrative, illustration of high points from the Tale. This particular hand-scroll might have been created as a bridal present. The Heian era illustrations set the style for the tradition of Tale of Genji illustrations in later centuries.

Context

Made by amateur court ladies for their pleasure and consumption. Additional paintings and text from the 12th Century hand-scroll:

Category:Illustrated Handscroll of The Tale of Genji (Tokugawa Art Museum)

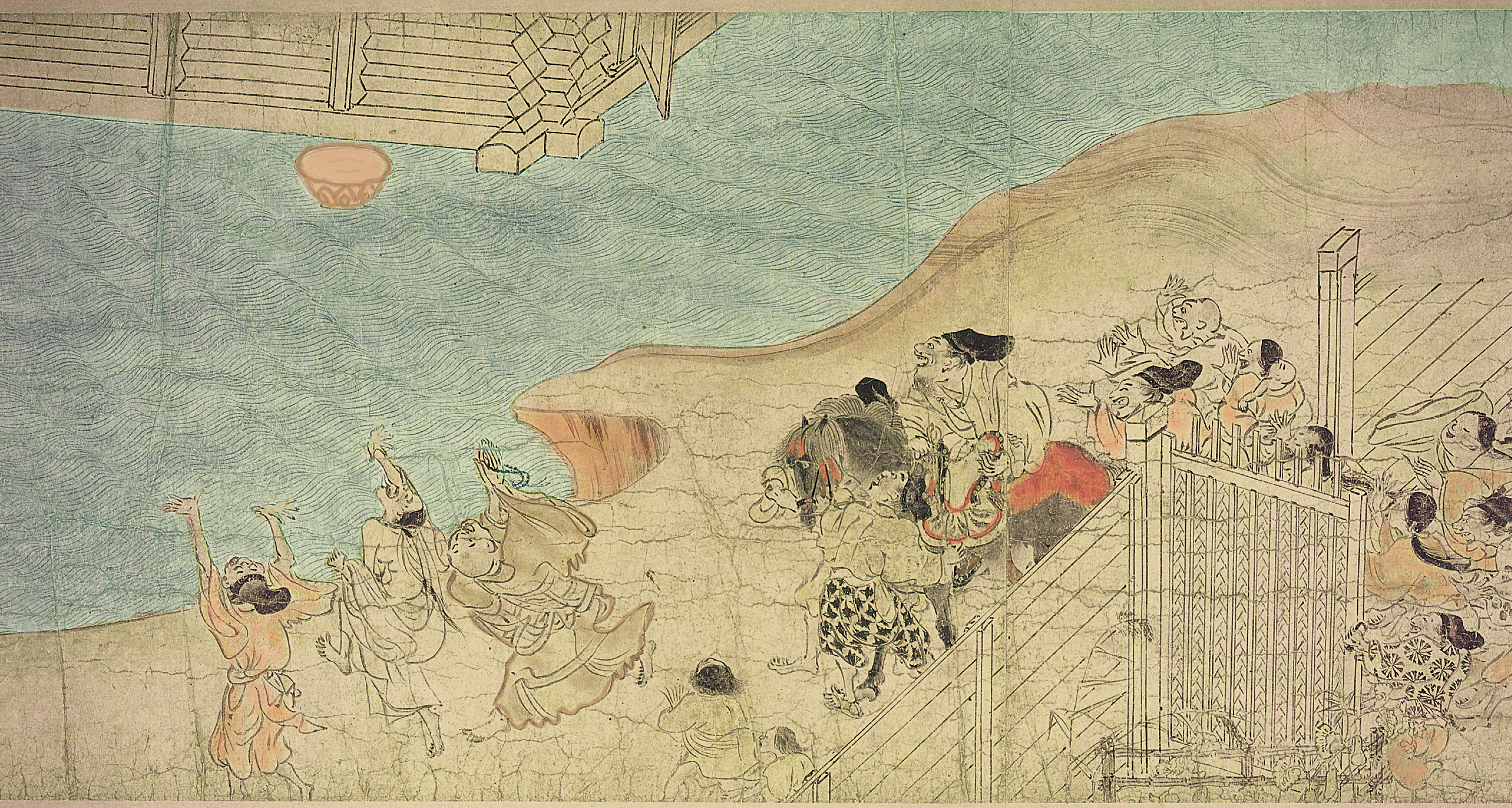

The Flying Storehouse

The Flying Storehouse:

Handscroll, ink and colors on paper, 1' ½" high

found in Chogosonshiji, Nara

Heian period

794 CE – 1185 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " This Heian handscroll illustrating a Buddhist miracle differs from the Genji scroll in both subject and style. The artist exaggerated each feature of the gesticulating and scurrying figures. "

This humorous narrative painting, a masterpiece of Japanese art, illustrated a folk tale about the founding of a temple in the countryside outside Kyoto, known as Mt. Shigi.

Form

Emaki/emaki-mono Hand-scroll: long continuous text followed by long continuous horizontal painting on paper with translucent watercolors and ink outlines.

Style

The style is completely different from the style of the Tale of Genji illustrations of around the same time: dynamic, cursive, cartoon-like, full of movement and surprise.

Meaning

It is likely that it is the work of a man, either a professional painter or a monk-painter. And it was created partly to educate, by explaining how the temple came to be at the top of Shigi-san, and to amuse, with the candid caricatures of peasants and rich landowners who aped the customs of the aristocracy.

Context

Part of lost traditions of narrative scroll painting in the Heian era. Preserved and passed down for many generations; obviously an object of great value.

Portrait statue of the priest Shunjobo Chogen

Portrait statue of the priest Shunjobo Chogen:

Painted cypress wood, 2' 8 ⅜" high

Todaji, Nara, Japan

Kamakura period

1185 CE –1332 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Chogen’s portrait statue, probably carved shortly after his death at age 86, is one of the most striking examples of the high level of naturalism prevalent in the early Kamakura period. It features finely painted details and a powerful rendering of the signs of aging, including sunken cheeks and eye sockets, lined face and neck, and slumping posture. Details such as his nervous handling of prayer beads capture the personality as well as the appearance of the priest. "

This is one of the earliest examples of realistic portraiture in Japanese art.

Form

3-D sculpture of a seated human figure; cypress wood and pigment details.

Style

Realism

Meaning

Shunjobo Chogen, a Japanese monk of the late 12th Century, was a hero of rebuilding and restoration projects in the ancient capital of Nara. He is celebrated for his persistence, holiness, and unselfishness. The toll of his personal sacrifices is evident in his thin body and elderly face. The image is preserved in the Todaiji temple, one of the temples burned during the civil war between the Minamoto and Taira clans, that the victorious Minamoto leader undertook to restore. Karma.

Context

Chinese sculptural and painting traditions of realism with respect to recording the physiognomy (or imagined physiognomy)

of pious Buddhist priests was already practiced in the Nara Period, when Japan was almost completely under the influence

of China in art and culture.

See 8th Century portrait of monk, Ganjin:

Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace

Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace:

Handscroll, ink and colors on paper, 1' 4 ¼" high

found in Kamakura, Japan

Kamakura period

1279 CE - 1368 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " A striking example of handscroll painting is Events of the Heiji Period, which dates to the 13th century and illustrates another facet of Japanese painting—historical narrative. The scroll depicts the civil-war battles at the end of the Heian period. The section reproduced here represents the nighttime attack on the Sanjo palace during which the retired emperor Goshirakawa (r. 1155–1158) was taken prisoner and his palace burned. Swirling flames and billowing clouds of smoke dominate the composition. Below, soldiers on horseback and on foot do battle. "

A world-renown masterpiece of Japanese narrative painting in the category of war tales.

Watch it unfold:

The Burning of Sanjo Palace - Traditional Japanese Music

Form

Emaki/emaki-mono Handscroll; short text followed by long, continuous illustration. Paper, ink, and watercolor.

Style

Vivid, full of dramatic movement and events, strong caricatures, calligraphic outlines reminiscent of the Shigisan-engi emaki

Meaning

History painting. The scroll vividly illustrates an episode from the civil war fought in Japan at the end of the 12th Century by two warring noble clans, the Taira and the Minamoto. The civil war is the subject of a long narrative text called the Heike Monogatari (Tale of Heike), compiled in 1240 CE. The Tale of the Heike

Context

The Heiji Rebellion, which is the subject of this scroll, took place in the Heiji era (1159-60); it records the audacious attack by the Minamoto clan of the Heian capital (Heian-kyo – today’s Kyoto) the kidnapping of a retired emperor, murder and mayhem, and the sack and burning of his palace located on Sanjo Avenue. Its illustration in the Kamakura period must be related to the history of the Minamoto clan now the first, and ruling Shogun, or military ruler.

Splashed Ink Landscape

Splashed Ink Landscape:

Ink on paper, full scroll 4' 10 ¼" x 1' ⅞"

found in Kyoto, Japan

Muromachi period

1333 CE – 1573 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Despite the prestige of Chinese art in Japan, few Japanese artists had the opportunity to travel to the mainland to study Chinese art or architecture firsthand. One who did was the renowned Muromachi painter Sesshu Toyo, who traveled to China with a trading mission between 1467 and 1469 and visited Buddhist monasteries, major cities, and famous scenic sites. "

Chinese Chan or Zen painting of the Southern Song Dynasty was introduced into Japan in the 14th Century as the samurai class became interested in aesthetic practices and in the study and practice of Zen meditation. Imported Chinese paintings, Zen themed or not, became very popular among the warrior class and Muromachi Period shoguns were avid collectors. The first Japanese artists to paint Zen in the Chinese style of artists like Liang Kai were Zen monks in Kyoto. They began by copying Chinese models, or like Sesshu, traveled to China to study. Sesshu is the most famous of the 15th Century Japanese Zen monk painters.

Form

Hanging Scroll, the Chinese format; ink on paper. The upper part of the painting is cut off in the illustration, and contains

an inscription:

The Burning of Sanjo Palace - Traditional Japanese Music

Landscape with ink broken

Style

Splashed-ink (haboku/hatsuboku literally, “broken ink”) the spontaneous, free style of Chinese Zen; washes ink combined with darker strokes; abstract, but enough information to make out tall mountain peaks in the distance, water in the foreground, a spit of land with trees and a teahouse on the shore, and men in fishing boats. How is this a Zen painting? The splashed-ink abbreviated style is part of the larger tradition of ink-painting (suiboku-ga, or sumi-e), styles that were passed on from Zen painters to professional artists, especially the artists of the Kano School, who made it one of their technical and stylistic hallmarks.

Meaning

Nonduality – an essential fact of Buddhism; non-distinction. And, admiration of Chinese zen painters.

Context

A document, a certificate of “graduation” for a student painter. See Inscription.

Chinese Lions

Chinese Lions:

Six-panel screen, ink, colors, and gold-leaf on paper, 7'4" x 14'10"

found in Kyoto, Japan

Momoyama period

1573 CE – 1615 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Appearing in both religious and secular contexts, lions were associated with power and bravery. Indeed, Chinese lions became an important symbolic motif during the Momoyama period. In Eitoku’s painting, the colorful beasts’ powerfully muscled bodies, defined and flattened by the characteristic Kano School heavy black outlines, stride forward in a schematic landscape of brown rocks and gold clouds. The dramatic effect of this work derives in part from its scale—it is more than 7 feet tall and nearly 15 feet long. "

In Japan, as the work of professional painters was highly demanded by wealthy patrons from the Imperial court, to the Kyoto nobility, to the Shogun and the samurai (warrior) class, and to members of the merchant class, styles and techniques were passed down from father to son as a family enterprise. One of the most important and successful of these families of artists was the Kano family, whose traditions were formed in the late Muromachi Period by the “father” of what came to be known as the “Kano School”, Kano Motonobu. Kano Eitoku, a descendent of Motonobu, became the most sought- after and successful profession artist of his day, patronized by the powerful leaders of the warrior class, such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the Momoyama Period, the late 16th Century.

Form

6-panel standing, folding screen. This format represents a large piece of furniture that was used in Japanese rooms as décor

and to create areas of focus, or privacy. The folding-screen form comes, like many cultural objects, from China. Folding

screens can have as few as two panels, and as many as eight, although 6 seems to be the most common, and often come

as a pair; they are designed to stand on their own in a zig-zag fashion, and are never meant to be displayed flattened

out as we see in museums, modern buildings, and study images.

What are some advantages of the format for painters?

Style

Kano School Style has its origins in Chinese ink-painting which is seen in the use of bold black outlines and washes to delineate all forms. Kano School paintings may be completely monochrome, or highly colorful. The colors, when used, are like those used in the Heian: thick opaque mineral colors. In addition, the Kano School developed the use of thin gold leaf squares attached to the surface of the paper ground, which creates an opulent effect and serves the practical purpose of reflecting light in dark interiors. The gold ground also serves to define large areas, which can be “read” as clouds, mist, or even sold ground. Overall the effect, a combination of flatness and 3-dimensionality, is grand and dynamic, suitable for expressions of wealth and power. The lions are more symbolic than realistic and are based on the artist’s imagination. Compare with Hasegawa Tohaku’s Pine Forest (text illustration 34-7)

Meaning

The lions, powerful animals, reflect the status and power of the samurai.

Context

Responding to the needs of the time for samurai leaders, like the large castles (see Himeji Castle, 34-5) built by feudal lords, paintings become symbols of power meant to impress others with opulence and power; costly materials available only to wealthy patrons. Painted as a gift – valuable item of exchange. Samurais have certain aesthetic tastes quite different from the court nobility.

Kogan

Kogan:

Shino glazed stoneware with underglaze iron slip decoration, 7 ¾" high

found in Kyoto, Japan

Momoyama period

1573 CE – 1615 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Wabi and sabi aesthetics underlie the ceramic vessels produced for the tea ceremony, such as the Shino water jar named Kogan. The name, which means “ancient stream bank,” comes from the brown-and-black painted design—marsh grass—on the jar’s surface as well as from its coarse texture and rough form, both reminiscent of earth cut by water. "

See front side:

During the 15th and 16th Century, corresponding to the late Ashikaga/Muromachi

and Momoyama periods, the samurai class became obsessed with Chanoyu (Tea Ceremony). The Tea Ceremony

was developed over time by a series of Tea Masters, of whom Sen no Rikyu, Tea Master to a succession of feudal

lords, was the most influential and the most famous. Many “schools” of Tea Ceremony stem from Rikyu’s practice and

are still valued and taught today. This simple water jar was created for use in Tea Ceremony, in the late Momoyama

period.

Form

A ceramic vessel designed to hold water accessed with a bamboo ladle. Flat bottom, wide mouth, and somewhat squat shape for

stability. It once had a lacquered wood cover with a handle, now lost.

Notice the emphasis on irregularity and imperfection. What do you see?

Style

“Shino Ware”: White glaze over under-glaze iron “slip” decorations of simple grasses and bamboo, like monochrome ink-painting.

Meaning

Reflects the aesthetic philosophy of Sen no Rikyu, which is the opposite of Kano School opulence and power, and meant convey

the Zen ideals of simplicity and humility.

Compare to Chinese porcelain of Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties.

Context

Feudal lords used the ritual of the Tea Ceremony as a kind of “meditation.” The Tea Master created a special, intimate event

for samurai to “cleanse” their minds through participation in the quiet ritual in which they observed the Tea Master

perform a series of choreographed movements meant to instill peace and harmony, and then partook in a bowl of thick

matcha green tea. Special rooms, even special structures surrounded by special gardens, were designed to create

the perfect atmosphere and space for this ritual. Rikyu’s most famous Teahouse is the Tai-an discussed in SG14. However,

Tea Ceremonies were also conducted in tents on the battlefield during this tumultuous time, when feudal lords were

vying for power among themselves. Tea ceremony objects, especially Tea Bowls by respected potters, were highly prized

and passed down as treasures within the family; several are designated as Japanese National Treasures.

The Secret Meaning of Traditional Japanese Tea Ceremony

The Tea Ceremony

Japanese tea ceremony utensils

Taian Teahouse

Taian Teahouse:

Myokian temple

found in Kyoto, Japan

Momoyama period

1573 CE – 1615 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " As the popularity of tea ceremonies increased, freestanding teahouses became common. The ceremony involves a sequence of rituals in which both host and guests participate. The host’s responsibilities include serving the guests; selecting special utensils, such as water jars and tea bowls; and determining the tearoom’s decoration, which changes according to occasion and season. "

Sen no Rikyū

Tai-an, tea room designed by Rikyu

Blueprints

This is one of only three teahouses thought to be designed by Rikyu. It forms the model for the continuing traditions

of Tea House architecture as practiced in the 21 st century."

Form

A small freestanding building containing a tearoom (chashitsu) and preparation rooms. Light in the Tearoom comes through white paper screens; the windows are staggered and do not show a view out. The entrance is a small half-door in with the participant crawls through. Across from the guest is a tokonoma, a specially raised alcove, unique to traditional Japanese architecture, that serves as a display space for ceramics, other interesting object, flower vase and often a painting or a scroll on the back wall – these are chosen to create a particular mood or ambience. The floors are raised platforms covered with thick straw mats called tatami. The size of the room is tiny, only two tatami mats, allowing for only one or two guests, and the Tea Master, who works silently around a small hearth in the corner near the tokonoma. All materials are plain, unvarnished, and natural.

Style

Rikyu-style. called So-an, or “grass hut” due to its studied and planned simplicity, similarity to a rustic hut.

Meaning

The expression of Rikyu’s philosophy of humility, articulated in the terms wabi, sabi, (lonely, worn, neglected, overlooked, lowly) which expressed values exactly the opposite of many brash samurai. Paradox? Conflict?

Context

The Tea Ceremony - A cultural development of immense proportions for Japan. The ideals, aesthetics, and principles of the Tea Ceremony express many aspects of Japanese culture that are unique in the world.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

The Great Wave off Kanagawa:

Woodblock print, ink and colors on paper, 9' ⅞ x 1' 2 ¾"

found in Tokyo, Japan

Edo period

1615 CE – 1868 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " In The Great Wave off Kanagawa, part of a woodblock series called Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji , the huge foreground wave dwarfs the artist’s representation of the distant mountain. This contrast and the whitecaps’ ominous fingers magnify the wave’s threatening aspect, enhanced by the fact that Japanese viewers knew Mount Fuji was an active volcano that had last erupted in 1707. The men in the trading boats bend low to dig their oars against the rough sea and drive their long, low vessels past the danger. "

How Did Hokusai Create The Great Wave?

The Edo Period (aka. Tokugawa Period, c.1600-1868) represents a long period of relative peace and tranquility

in Japan after centuries of civil war. Tokogawa Ieyasu, the last of three powerful feudal lords of the Momoyama

period, was able to unify the country and rule as the Shogun. The Tokugawa family remained in military power for the

next 250 years. During this time Eastern Japan saw extensive development. The new city of Edo (Tokyo) was constructed

and populated with people from all classes of society. The Shogun occupied a large castle complex in the center of

the city, with the estates of his closest allies forming a circle around him. The citizens lived in various parts

of the city, primarily near the coast where mercantile trade was carried out. Artisans and craftsmen were in demand,

the arts and crafts flourished, especially wood-block print publications, which appealed to all classes.

Ukiyo-e: “Pictures of The Floating World.” While the Tokugawa rule was strict and controlling, it allowed for

zoned areas of Edo called the pleasure quarters, where theater, sumo wrestling, tea-houses (not Tea Ceremony) and

brothels were allowed to conduct business. This became known as Ukiyo (Floating world), a reference to the

Buddhist notion of impermanence, brevity of life, fleeting pleasures. Publishers put out popular novels, with illustrations.

Gradually the illustrations took on a status of their own, and these wood-block prints became great collectors’ items,

known as Ukiyo-e. In the middle of the 18th Century the print designer, Suzuki Harunobu, designed the first multi-colored

print, and after that, multi-colored prints (known as nishiki-e, or “Brocade Prints,”) were being put out by all publishers.

The publishers employed profession print designer, like Harunobu and many others, who worked in what became a highly

competitive “graphic” design field. Several great designers became famous in their own time and in great demand: Utamaro,

Hokusai, and Hiroshige, for example.

Form

Wood-block print on paper. A hand-made object, created by a team of artists and craftsmen: the designer submits the model

as an original ink and watercolor drawing; block carvers reverse the design and translate the drawing onto a block,

one for each color, the ink lines and each color separately. A printer then prints the image using one block after

another until all the colors are represented.

Watch and see how labor intensive the process is:

Ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking with Keizaburo Matsuzaki

Style

Each print designer had his own style, although they shared several categories of subject matter: sumo wrestlers, kabuki actors in their signature roles, beautiful women, and landscapes. Some artists employed the traditional bird’s-eye perspective, but by Hokusai’s time European one-point perspective was known and often used by print designers, Hokusai and Hiroshige particularly.

Meaning

The series, to which this print belongs, 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, is Hokusai’s idea and creation. It takes Mt. Fuji, a volcanic peak visible to the West of Edo, and often covered with snow, and makes it a star by showing it from 36 (actually 46) different locations around the mountain. It’s cleverness and skill were immediately recognized and admired, the series collected, and much imitated.

Context

A “popular” art form that flourished alongside art created for samurai and imperial family.