Islam | Study Guide Images

View the study guide images for this region. You can access each study guide image and its information by clicking on the corresponding tab. Feel free to rearrange the tabs by clicking and dragging them over one another. Click on the menu icon to reset the accordion. Hovering over the menu icon allows you to navigate to a study guide image you wish to see.

Dome of the Rock

Dome of the Rock:

Shine taking form of an octagon with a towering dome

found in

Jerusalem, Isreal

Umayyad Caliphate

661 CE – 750 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " In its form, construction, and decoration, the Dome of the Rock is firmly in the Late Antique tradition of the Mediterranean world. It is a domed central-plan structure descended from the Pantheon in Rome and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, but it more closely resembles the octagonal San Vitale in Ravenna. According to the historian Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Muqaddasi (946–1000), who was born in Jerusalem, the inspiration for the Dome of the Rock was a neighboring Christian monument, Constantine’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Al-Muqaddasi also reported that Abd al-Malik judged the church to be so magnificent that it “dazzled Muslim minds,” and therefore the caliph decided to construct an even greater shrine. The Christian domed rotunda bore a family resemblance to the roughly contemporaneous Constantinian mausoleum later rededicated as Santa Costanza in Rome. Crowning the Islamic shrine is a 75-foot-tall double-shelled wood dome, which so dominates the elevation as to reduce the octagon to functioning visually merely as its base. This soaring, majestic unit creates a decidedly more commanding effect than that of similar Late Antique and Byzantine domical structures. The silhouettes of those domes are comparatively insignificant when seen from the outside. "

This octagonal building, which is not a mosque, is the oldest Islamic structure in the world. Built by Umayyad Dynasty caliph, Abd’al Malik, it is a shrine covering a sacred rock from which Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven with the Angel Gabriel on the famous “Night Journey.”

Form

The form, a domed structure supported by pillars and arches is Roman. Islamic architects borrowed it because it was a common, rational, functional architectural form close at hand. Moreover, they used recycled stones and pillars from Roman buildings. (see Chapter 7 on Roman architectural Basics). At the same time, Christian churches were also borrowing Roman architectural forms. (see Chapter 8 on early Christian churches). The advantage of a large dome is that it commands attention from a distance, especially when covered with gold.

Style

It is a hybrid style, borrowing several elements of Roman architecture including the use of mosaics to decorate the surfaces of walls. Only the interior décor is original. Here the motif known as the arabesque is prominent, as well as the decorative power of Arabic calligraphic writing and the spiritual power of the holy word.

Meaning

Abd’al Malik’s intention was to erect a magnificent structure to announce his conquest of Jerusalem and to rival the nearby Christian monument, Emperor Constantine’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. He succeeded.

Context

The strong political overtones of this building equal its aesthetic success and are as alive today as they were in the 7th Century: the placement of the Dome of the Rock at the top of the citadel known to Jews as the Temple Mount, the site of the once great Temples of Solomon (destroyed by the Babylonians) and the 2nd Temple (destroyed by the Romans – see the Arch of Titus in Rome, 7-41), the western foundation wall of which is known as the “Wailing Wall,” a place of lamentation.

Prayer Hall of the Great Mosque

Prayer Hall of the Great Mosque:

36 piers and 514 columns support a unique series of double-tiered horshoe-shaped arches

found in

Córdoba, Spain

Umayyad Caliphate

661 CE – 750 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The most important building project the Umayyad dynasty undertook at Córdoba was the erection of a great mosque on the site of a Visigothic church, thereby marking the triumph of Islam in Spain, as before in Jerusalem (see Architecture ). Begun in 784 by Abd al-Rahman I and enlarged several times during the next two centuries, Córdoba’s Mezquita (Spanish, “mosque”) eventually became one of the largest mosques in the Islamic West. The hypostyle prayer hall has 36 piers and 514 columns topped by a unique system of double-tiered arches that carried a timber roof (later replaced by vaults). The two-story system was the builders’ response to the need to raise the roof to an acceptable height using short columns that had been employed earlier in other structures, both Visigothic and Roman. The lower arches are horseshoe-shaped, a form perhaps adapted from earlier Mesopotamian architecture or of Visigothic origin. In the West, the horseshoe arch quickly became closely associated with Muslim architecture. Visually, these arches seem to billow out like windblown sails, and they contribute greatly to the light and airy effect of the Córdoba mosque’s interior. "

Basic elements of a Mosque: a large covered gathering place for communal

prayer,

ideally large enough to hold the entire community (the Great Mosque or the Friday Mosque):

common

early mosque forms were hypostyle halls with rows of columns holding up a

flat

roof. The mihrab a niche in the wall facing the direction of Mecca; this

identifies

the direction of prayer qibla visible on both the inside and outside of the

mosque, often covered with a dome. An open courtyard or forecourt protected by a fortified

wall

enclosing all the mosque space; a fountain for ablutions in the courtyard and a garden

(foretaste

of Heaven); a minaret, a tall tower from which a cantor calls the faithful

to

prayer at the proper times. See the Great Mosque at Kairouan, Tunisia.

The Umayyad ruler, Abd’al Rahman, escaped imminent assassination

by

rivals and fled first to North Africa and then to Spain in 750 CE, which had been under Arab

rule since the early 8th Century. His dynasty lasted three centuries, during

which

time the Umayyads presided over the golden age of Islamic culture (Al-Andalus) in Spain.

Form

Hypostyle hall: enlarged several times over the centuries. Unusual double arches necessitated by the short height of the columns and capitals obtained as recycled building material from pre-existing Roman and Christian buildings. Unusual “horse-shoe” shaped arches that became emblematic of Muslim architecture.

Style

Hybrid – the adaptation of existing architectural forms to custom and cultural traditions brought with to Spain with Islam; another unusual feature is the alternation of red brick and cream color stonework of the arches.

Meaning

The Great Mosque of Cordoba is a symbol of the original ecumenism of Islam; rather than replacing Christianity with Islam they each worshipped in the same building until the Muslims bought the Christians out. The beauty and the intended aesthetic effects are always for the glory of Allah.

Context

The mosque was partly converted into a Christian cathedral after the fall of Cordoba in the 13th Century.

Maqsura of the Great Mosque

Maqsura of the Great Mosque:

Highly decorative multiobed arches

found in

Córdoba, Spain

Umayyad Caliphate

661 CE – 750 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Also dating to the caliphate of al-Hakam II is the mosque’s extraordinary maqsura, the area reserved for the caliph and connected to his palace by a corridor in the qibla wall. The Córdoba maqsura is a prime example of Islamic experimentation with highly decorative multilobed arches (which are subsidiary motifs in the contemporaneous gate. "

When Abd’al Hakam II became caliph in 961 he undertook an extensive renovation of the mosque. Most noteworthy are the maqsura, the mihrab, and the complex dome over the mihrab.

Form

A special space was set aside in front of the mihrab for the exclusive use

of

the caliph, who entered directly from his palace through a corridor in the qibla

wall.

The space was articulated by a new, more complex form of horse-shoe arches with multiple

lobes

and the illusion of intersecting arches above and below. The mihrab was replaced with an

elaborate,

deeply recessed niche decorated with gold tesserae arabesques and calligraphy, and covered

with

a high dome characterized by octagonal lobes and supported by 8 crossing ribs.

Search for 'the great mosque at cordoba mihrab'

Style

Unique and ingenious, gorgeous, glory expressed in precious materials.

Meaning

Speaks to the incredible quality and imagination of the Spanish Muslim architects and designers.

Context

The Umayyad Caliphate at Cordoba was a beacon of learning and intellectual activity in the arts and sciences, producing great philosophers, logicians, astronomers, and keepers of Greek classical wisdom. Jewish philosophers, like the great Maimonides, were equally respected in Al-Andalus.

Mosque of Selim II

Mosque of Selim II:

Dome-covered square prayer hall

found in

Edirne, Turkey

Ottoman Empire

1281 CE – 1924 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Sinan’s vision found ultimate expression in the Mosque of Selim II at Edirne, which had been the capital of the Ottoman Empire from 1367 to 1472 and where Selim II (r. 1566–1574) maintained a palace. There, Sinan designed a mosque with a massive dome set off by four slender pencil-shaped minarets (each more than 200 feet high, among the tallest ever constructed). The dome’s height surpasses that of Hagia Sophia’s dome (see “ Sinan the Great and the Mosque of Selim II ”). But it is the organization of the Edirne mosque’s interior space that reveals Sinan’s genius. The mihrab is recessed into an apselike alcove deep enough to permit window illumination from three sides, making the brilliantly colored tile panels of its lower walls sparkle as if with their own glowing light. (In all, there are almost 300 windows in the Edirne mosque to flood the interior with sunlight.) The plan of the main hall is an ingenious fusion of an octagon with the dome-covered square. The octagon, formed by the eight massive dome supports, is pierced by the four half-dome-covered corners of the square. The result is a fluid interpenetration of several geometric volumes that represents the culminating solution to Sinan’s lifelong search for a vast yet unified interior space. Sinan’s forms are clear and legible, like mathematical equations. Height, width, and masses relate to one another in a simple but effective ratio of 1:2, and precise numerical ratios similarly characterize the complex as a whole. The forecourt of the building, for example, covers an area equal to that of the mosque proper. Most architectural historians regard the Mosque of Selim II as the climax of Ottoman architecture. Sinan proudly proclaimed it his masterpiece. "

In this module, we will focus on art created by and for Islam. This will take us on a geographic journey from the Arabian Peninsula, West to Spain and North Africa, and East and Northeast as far as India (and China, although we will not include Muslim China in our investigations). We will also cover several centuries, from the 7th to the 17th and study major works of architecture, painting, calligraphy, and the decorative arts.

Form

The mosque design is new and deliberately derived from the earlier design of the Byzantine church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, which was built in the 6th Century in Constantinople/Istanbul. (See Chapter 9 – Byzantine Art). The Greek architects who designed Hagia Sophia succeeded in placing a large dome over a large square space through the use of pendentives and squinches. A clerestory around the base of the dome allowed for light to penetrate the space. Sinan the Great adapted this design to his mosques, inspired by how earlier Muslim architects had retrofitted Hagia Sophia for use as a mosque after the fall of Constantinople.

Style

A hybrid, part Byzantine, part Ottoman. The most important contribution is the way natural daylight is brought into mosque interiors, perhaps for the first time.

Meaning

The Mosque of Selim II is considered the culmination of Ottoman architecture.

Context

First Sulieman the Magnificant, then his successor Selim II, used architecture to make statements of hegemony and political power. In the context of Islam, mosques of this size and location served important secular and economic as well as religious functions: schools (madrasa), hospitals, charity distribution centers, markets, etc.

Imam Mosque (Shah Mosque)

Imam Mosque (Shah Mosque)

:

The ceramists who produced the cuerda seca tiles of the murqanas-filled portal to the

Imam Mosque had to

manufacture a wide variety of shapes with curved surfaces to cover

the hall's arches and vaults.

found in

Isfahan, Iran

Abbasid - Safavid Dynasties

750 CE - 1732 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Cuerda seca tiles are polychrome and can bear complex geometric and vegetal patterns as well as Arabic script more easily than can mosaic tiles. They are also more economical to use because vast surfaces can be covered with large tiles much more quickly than they can with thousands of smaller mosaic tiles. But when builders use cuerda seca tiles to sheathe curved surfaces (vaults, domes, minarets), the ceramists must fire the tiles in the exact shape required—a daunting challenge. Polychrome tiles have other drawbacks. Because the ceramists fire all the glazes at the same temperature, cuerda seca tiles are not as brilliant in color as mosaic tiles and do not reflect light the way the more irregular surfaces of tile mosaics do. The preparation of the multicolored cuerda seca tiles also requires greater care. To prevent the colors from running together during firing, the potters outline the motifs with cords containing manganese, which leaves a matte black line between the colors after firing. "

Islamic Architecture

Imam Mosque Isfahan Iran

A savoring of architectural and decorative details.

Form

The mosque form from Iran are unique; they comprise several distinct features: iwan – a vaulted space that opens on one side of the courtyard; there are usually 4 placed in the center of each side of the courtyard; they are articulated by pishtaq – a rectangular flat frame surrounding the opening in the form of a pointed (ogival) arch and the interior surface of which is often broken up by muqarnas – three-dimensional beehive like cells that may be further faceted, and which create visual interest and light effects in the bright sun. The interior and exterior surfaces are covered with glazed ceramic tile work called cuerda seca (dry cord). There are also often reflecting pools in the central courtyard.

Style

Unique and singular; every surface covered with décor in brilliant, cool colors.

Meaning

Unsurpassed technical skill in the creation and application of ceramic glazed tiles to curved surfaces.

Context

Example of the wealth and command of talent available to the Shahs of Islamic Persia.

Mihrab

Mihrab:

Glazed mosacic tilework, 11' 3" x 7' 6"

found in

Isfahan, Iran

Abbasid - Safavid Dynasties

750 CE - 1732 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " At the time the Ottomans were establishing their empire in Turkey, Iran underwent a period of political upheaval until the arrival of the forces of Timur in the late 14th century (see Luxury Arts ). Isfahan, the former Seljuk capital, was, in fact, under siege in 1354 when the Madrasa Imami was constructed. Its mihrab is an early masterpiece of Iranian ceramic tilework (see “ Islamic Tilework ”). As already noted, verses from the Koran appeared in the mosaics of the Colossal head in Jerusalem and in mosaics and other media on the walls of countless later Islamic structures. Indeed, some of the masterworks of Arabic calligraphy are not in manuscripts but on walls. The Madrasa Imami mihrab, like the earlier mihrab in the winter prayer hall of Isfahan’s Friday Mosque, exemplifies the perfect aesthetic union between the Islamic calligrapher’s art and abstract ornamentation. The pointed arch framing the mihrab niche bears an inscription from the Koran in Kufic, the stately rectilinear script employed for the earliest Korans. Many supple cursive styles also make up the repertoire of Islamic calligraphy. One of these styles, known as Muhaqqaq, fills the mihrab’s outer rectangular frame. The mosaic tile decoration on the curving surface of the niche and the area above the pointed arch consists of tighter and looser networks of geometric and abstract floral motifs. The mosaic technique is masterful. Every piece had to be cut to fit its specific place in the mihrab—even the tile inscriptions. The ceramist smoothly integrated the subtly varied decorative patterns with the framed inscription in the center of the niche—proclaiming that the mosque is the domicile of the pious believer. The mihrab’s outermost inscription—detailing the Five Pillars of Islamic faith (see “ Muhammad and Islam ”)—serves as a fringelike extension, as well as a boundary, for the entire design. The unification of calligraphic and geometric elements is so complete that only the practiced eye can distinguish them. The artist transformed the architectural surface into a textile surface—the three-dimensional wall into a two-dimensional hanging—weaving the calligraphy into it as another cluster of motifs within the total pattern. "

Form

Typical Iranian mihrab: pishtaq and ogival (pointed) arch opening. The form has been removed from a madrasa (theological school) in Isfahan. Exquisite example of the skill and workmanship of Iranian tile makers and installers.

Style

Floral and geometric arabesque patterns; calligraphy (Arabic texts mainly from the Koran) are also used as ornament: kufic – an angular, rectilinear style of writing is seen in dark script on a white ground around the arch opening. Muhaqqaq, a more cursive and flowing form of script is seen along the outer frame of the pishtaq, and in the framed rectangular phrase set low into the interior back wall of the niche. The style of décor is not unique to the mihrab but can be found in a variety of forms, including textiles.

Meaning

All mihrabs, wherever they are, indicate the direction of Mecca. Does this one? The Arabic.

Context

Originally located within a theological school (for men); several mihrabs from the same building are found in museum collections other than the MET. Why do you think this is? Why are they no longer in situ (in their original location)?

Carpet From Funerary Mosque of Shaykh Safi al-Din

Carpet From Funerary Mosque of Shaykh Safi al-Din:

Wool and Silk 34' 6" x 17' 7"

found in

Ardabil, Iran

Safavid Dynasty

1501 CE – 1736 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The design consists of a central sunburst medallion, representing the inside of a dome, surrounded by 16 pendants. Mosque lamps (appropriate motifs for the Ardabil funerary mosque) hang from two pendants on the long axis of the carpet. The lamps are of different sizes. This may be an optical device to make the two appear equal in size when viewed from the end of the carpet at the room’s threshold. Covering the rich blue background are leaves and flowers attached to delicate stems that spread over the whole field. The entire composition presents the illusion of a heavenly dome with lamps reflected in a pool of water full of floating lotus blossoms. No human or animal figures appear, as befits a carpet intended for a mosque, although they can be found on other Islamic textiles used in secular contexts, both earlier and later. "

Ardabil, near the Western shore of the Caspian Sea, was known as the center of silk and carpentry. It is also the location of the Ardabil Shrine, where the founder of the Safavid Dynasty and a Sufi leader, who died in 1334, is laid to rest. It was a place of pilgrimage, and the shrine was remodeled and enlarged several times over the centuries. In the 1530s Shah Tahmasp commissioned a pair of carpets for the interior from the master carpet designer, Maqsud of Kashan (whose signature is on the carpets).

Form

Hand woven, over 25 million tiny knots; Textile, of wool and silk threads.

Style

Organization of the design is based on repetition, bi-lateral symmetry, radial symmetry.

Meaning

As a floor covering it brings beauty to the floor; as a design, it suggests a rectangular pool of water whose surface is covered with floating blossoms and which reflects the high ceiling above it with a central dome and hanging lanterns.

Context

After an earthquake in the late 19th Century the carpets were sold; the carpet in London was purchased on the advice of William Morris in 1893. What happened to the second carpet?

- On Sufism:

Sufism

- On Persian Carpets:

Persian

Carpets

- On Kashan weaving:

Traditional

skills of carpet weaving in Kashan

Seduction of Yusuf

Seduction of Yusuf:

Ink and color on paper, 11' 7/8" x 8' 5/8"

found in

Herat, Afghanistan

Timurid Dynasty

1370 CE – 1507 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The most famous Persian painter of his age was Bihzad, who worked at the Herat court before migrating to Tabriz. At Herat, he illustrated the sultan’s copy of Bustan (The Orchard) by the Persian poet Sadi (ca. 1209–1292). One page represents a story in both the Bible and the Koran—the seduction of Yusuf (Joseph) by Potiphar’s wife, Zulaykha. Bihzad dispersed Sadi’s text throughout the page in elegant Arabic script in a series of beige panels. According to the tale as told by Jami (1414–1492), an influential mystic theologian and poet whose Persian text appears in blue in the white pointed arch of the composition’s lower center, Zulaykha lured Yusuf into her palace and led him through seven rooms, locking each door behind him. In the last room, she threw herself at Yusuf, but he resisted and was able to flee when the seven doors opened miraculously. Bihzad’s painting of the story highlights all the stylistic elements that brought him great renown: vivid color, intricate decorative detailing suggesting luxurious textiles and tiled walls, and a brilliant balance between two-dimensional patterning and perspective depictions of balconies and staircases. Bihzad’s apprentices later worked for the Mughal court in India and introduced his distinctive style to South Asia (see Mughal Empire ). "

Art of Timurid: The Art of the Timurid Period (ca. 1370–1507)

Bustan (the Orchard), a poetic collection of experiences and

aphorisms

by Saadi, c. 1257.

Form

A page of illustration from a book owned by the Sultan Husain Mayqara.

Style

What is uniquely “Persian:” most obvious is the treatment of space, which can be dizzying,

especially in the representation

of interior spaces such as we have here in the scene of Joseph escaping from the clutches of

Potifar’s wife. It results from combining different viewpoints and interchanging static

patterns

that create a sense of flatness with a sense of 3-Dimensionality. Also typical are the

brilliant,

jewel-like colors and the way figures seem to “fly.”

As in

Islamic décor, calligraphic text is used not only for information, but as part of the

design.

Finally, exploding from the margins, as if the scene is breaking out of its borders, is a

unique

feature of Iranian manuscript painting.

Meaning

The original story comes from the Hebrew Scriptures, also known as the “Old

Testament.”

It is an example of how Christians, Jews, and Muslims, notwithstanding

their many differences,

emerge from common sources and share many stories.

Context

Patronizing and supporting artists’ workshops was an important activity of Persian rulers. The artist, Bihzad (1460-1535), was one of the most famous painters of his time; it is his students who will go to India to found a painting workshop at the court of the Mughals.

The Great Mosque

The Great Mosque :

adobe (sun-dried mud-brick) and wood

found in

Djenne, Mali

Djenne Culture

1100 CE – 1500 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " One of the most ambitious examples of adobe (sun-dried mud-brick) architecture in the world is Djenne’s Great Mosque, originally built in the 13th century by the first Djenne king to convert to Islam, and reconstructed in 1906–1907. (The mosque had been razed in 1830 by a Muslim ruler who judged its size and lavish decoration to be offensive to the tenets of his faith.) The mosque has a large courtyard in front of a roofed prayer hall, emulating the plan of many of the oldest mosques known (see “ The Mosque ”)—for example, the Great Mosques at Damascus in Syria and at Kairouan in Tunisia. Djenne’s qibla wall faces Mecca, as do all qibla walls, but the mosque’s facade is unlike that of any other Islamic shrine. It features soaring adobe towers and vertical buttresses resembling engaged columns that produce a majestic rhythm. The many rows of protruding wood beams further enliven the walls but also serve a practical function as perches for workers undertaking the essential recoating of sacred clay on the exterior that occurs during an annual festival. "

Great Mosque of Djenné

Jihadist pleads guilty to destroying ancient Timbuktu artifacts

Form

Resembles the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia (9th Century) located across the Sahara Desert on Africa’s Mediterranean coast, with its large fortified courtyard and a flat roofed prayer hall (See Chapter 10:10-7 and 8. Compare. The material is baked mud or adobe.

Style

An adaptation of the Umayyad mosque forms with allowances made for differences and limitations of material.

Meaning

Ingenuity of craftspeople everywhere. Power to build.

Context

Mali, located along the floodplains of the Niger River, lies along important trade routes between North and West Africa, which explains how a Tunisian mosque form comes to be built in Djenne. Islam lived side by side with native religious practices and figurative artwork in terracotta that we will encounter in the final module: Africa.

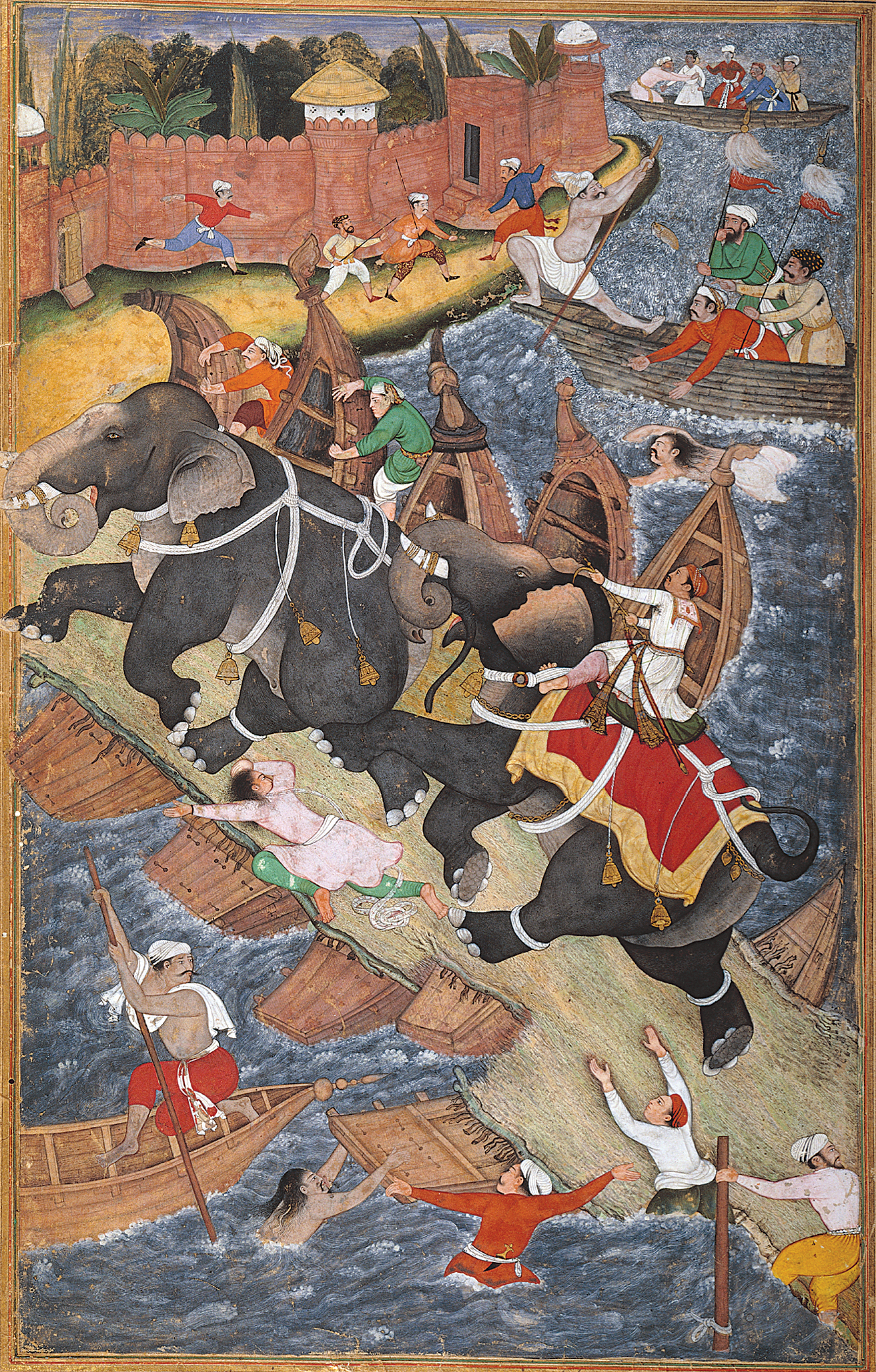

Akbar and the Elephant Hawai

Akbar and the Elephant Hawai:

Opaque watercolor on paper, 1' 1 ⅞" x 8 ¾"

found in

Delhi, India

Mughal Empire

1526 CE – 1857 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Akbar also commissioned Abul Fazl (1551–1602), a member of his court and close friend, to chronicle his life in a great biography, the Akbarnama (History of Akbar ), which the emperor asked his painters to illustrate. One of the full-page illustrations, or so-called miniatures (see “ Indian Miniature Painting ”), in the emperor’s personal copy of the Akbarnama was a collaborative effort between the painter Basawan, who designed and drew the composition, and Chatar Muni, who colored it. The painting depicts the episode of Akbar and Hawai, a wild elephant that the 19-year-old ruler had mounted and pitted against another ferocious elephant. When the second animal fled in defeat, Hawai, still carrying Akbar, chased it to a pontoon bridge. The enormous weight of the elephants capsized the boats, but Akbar managed to bring Hawai under control and dismount safely. The young ruler viewed the episode as an allegory of his ability to govern—that is, to take charge of an unruly state. For his pictorial record of that frightening day, Basawan chose the moment of maximum chaos and danger—when the elephants crossed the pontoon bridge, sending boatmen flying into the water. The composition is a bold one, with a very high horizon and two strong diagonal lines formed by the bridge and the shore. Together these devices tend to flatten out the vista, yet at the same time, Basawan created a sense of depth by diminishing the size of the figures in the background. He was also a master of vivid gestures and anecdotal detail. Note especially the bare-chested figure in the foreground clinging to the end of a boat; the figure near the lower right corner with outstretched arms, sliding into the water as the bridge sinks; and the oarsman just beyond the bridge who strains to steady his vessel while his three passengers stand up or lean overboard in reaction to the surrounding commotion. "

Crash course in Mughal History by John Green:

The Mughal Empire and

Historical Reputation: Crash Course World History #217

The 13th C. Delhi Sutanate was first Islamic rule in India, but the greatest was the rule of the Mughals, founded by Babur in the early 16th Century after subordinating the local Rajput (Hindu) rulers. Babur’s successor Humayun, lived in exile for a time at the Persian court of Shah Tahmasp until he could return to India in 1555. As a gift Shah Tahmasp sent Humayun home to Delhi with two master Persian painters from the Court Painting Workshop, trained by Bihzad. These painters established a Painting Workshop at the Mughal Court that produced hundreds of illustrated book manuscripts and engravings of history, religion, and sciences. The highest point of Mughal intellectual culture was achieved under the rule of Akbar the Great, whose reign corresponded with the great achievements of the Italian Renaissance popes and aristocrats. In fact, there were numerous Western philosophers and Catholic priests residing in Delhi at the pleasure of the Emperor.

Form

Book illustration on paper (Mughal “miniature”) with watercolor (gouache).

Style

A hybrid style that combines the naturalism of Indian painting with the abstraction and birds-eye- perspective of Persian painting, and even some European influence in the illusion of distance. Can you see how seamlessly the combination works to create a scene of great action and dynamism?

Meaning

The Akbarnama, was composed by the court scribe Abul-Fazl in Persian. It is a day to day record of the life and activities of Akbar, with an emphasis on his heroic deeds and unsurpassed abilities. Here we see Akbar bringing a rogue elephant under submission. Akbar commissioned illustrations from the painting workshop of over 40 resident artists, and two native Indian artists, Basawan and Chatar Muni, clearly great masters collaborated on this example, with Chatar Muni providing the under sketch and Basawan the color.

Context

Akbar’s court was a place of freedom of philosophical discussion and inter-religious

tolerance. Christian missionaries who

were at court brought illustrated books and engravings with them from Europe as gifts;

from

an examination of these Indian Mughal artists became aware of European techniques of

illusionism

and used them in their paintings when they liked.

What happened to the Mughal

art collections after their conquest by the British?

Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal:

Detail of the pietra dura stonework of the area above the central niche of the facade of

the Taj Mahal

found in

Agra, India

Mughal Empire

1526 CE – 1857 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Monumental tombs were not part of either the Hindu or Buddhist traditions but had a long history of Islamic architecture. The Delhi sultans had erected tombs in India, but none could compare in grandeur to the fabled Taj Mahal at Agra. Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658), Jahangir’s son, built the immense mausoleum as a memorial to his favorite wife, whose official title was Mumtaz Mahal (1593–1631), or “Chosen of the Palace.” Taj Mahal means “Crown Palace,” and the mausoleum eventually became the ruler’s tomb as well. It figures prominently in official histories of Shah Jahan’s reign (see “ Abd al-Hamid Lahori on the Taj Mahal ”). The dome-on-cube shape of the central block has antecedents in earlier Islamic mausoleums and other Islamic buildings, such as the Alai Darvaza at Delhi, but modifications and refinements in the design of the Agra tomb converted the earlier massive structures into an almost weightless vision of glistening white marble. The Agra mausoleum seems to float magically above the broad water channels and tree-lined reflecting pools punctuating the fountain-filled garden leading to it. Reinforcing the illusion of the marble tomb being suspended above water is the absence of any visible means of ascent to the upper platform. A stairway does exist, but the architect intentionally hid it from the view of anyone who approaches the memorial. The Taj Mahal follows the traditional char-bagh (“four-plot”) plan of Iranian garden pavilions, which symbolized the Koranic Garden of Paradise. Today, however, the mausoleum appears to stand at the northern end of the garden on the edge of the Yamuna River, rather than in the center of the formal garden, as it should in a charbagh plan. Originally, the gardens extended to the other side of the river, and the Taj Mahal did, in fact, occupy a central position. The tomb itself is octagonal in plan and has typically Iranian arcuated niches on each side. The interplay of shadowy voids with light-reflecting marble walls that seem paper-thin creates an impression of translucency, further enhanced by the pietra dura inlay of precious and semiprecious stones in the stone walls. The pointed arches lead the eye in a sweeping upward movement toward the climactic dome, shaped like a crown (taj). Four carefully related minarets and two flanking triple-domed pavilions enhance and stabilize the soaring form of the mausoleum. The designer—probably Ustad Ahmad Lahori (d. 1649), Shah Jahan’s chief court architect—achieved this delicate balance between verticality and horizontality by strictly applying an all-encompassing system of proportions. The Taj Mahal (excluding the minarets) is as wide as it is tall, and the height of its dome is equal to the height of the facade. The mausoleum is a unique and brilliant fusion of Islamic, Hindu, and Byzantine elements. "

The Taj Mahal Videos

Taj Mahal

Form

Although it has the appearance of a mosque, it is a mausoleum where the wife of Shah Jehan (Jahan), who died giving birth to her 14th child, is entombed. Shah Jehan’s tomb was eventually placed there as well. The ground plan of the mausoleum is octagonal resting on a square. The proportions are close to 1:1, height equals width.

Style

A beautiful, seamless hybrid of several cultural forms associated with Islam. The building is treated like an inlaid jewel box: the marble surfaces are inlaid with exquisite floral and geometric arabesques (like those at Isfahan) in precious stones of different colors. The long reflecting pool doubles the impact of the building, which changes color in the light. What features of the architecture can you trace back to other Islamic buildings we have seen?

Meaning

Famously, the building is an act of loving devotion by a grieving husband; a monument to love. It is said that the four towers (which resemble minarets) are like poles supporting the blue tent of the sky.

Context

Deemed by all the finest architectural achievement of Mughal India.