Americas| Study Guide Images

View the study guide images for this region. You can access each study guide image and its information by clicking on the corresponding tab. Feel free to rearrange the tabs by clicking and dragging them over one another. Click on the menu icon to reset the accordion. Hovering over the menu icon allows you to navigate to a study guide image you wish to see.

Colossal head

Colossal head:

Basalt 9' 4" high

found in

La Venta, Mexico

Olmec Culture

1200 BCE - 400 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Four colossal basalt heads, weighing about 10 tons each and standing between 6 and 10 feet high, face out from the plaza. Archaeologists have discovered more than a dozen similar heads at San Lorenzo and Tres Zapotes. Almost as much of an achievement as the carving of these huge stones with stone tools was their transportation across the 60 miles of swampland from the nearest known basalt source, the Tuxtla Mountains. Although the identities of these colossi are uncertain, their individualized features and distinctive headgear and ear ornaments, as well as the later Maya practice of carving monumental ruler portraits, suggest that the Olmec heads portray rulers rather than gods. The sheer size of the heads and their intensity of expression evoke great power, whether mortal or divine."

The Olmec Culture of the northern gulf-coast of Mexico is the oldest identified culture in Meso-America. Sometimes referred to as the “mother culture” for Meso-America, multiple features of the Olmec, such as a reverence for green jade stone, plazas and public ceremonial centers, pyramid temples, stone sculpture, the ball-game, murals, ceramics, blood sacrifice, and even possibly hieroglyphic writing, are found in all of the later cultures that followed the Olmec and developed in the larger geographic area of Mexico and Central America: Maya, Aztec, etc.

Form

Freestanding, large-scale, three-dimensional basalt sculpture of a human head represented from the chin up.

Style

The representation of the head is based on human proportions that have been subtly squared, rounded, and possibly flattened, as if the shape of the boulder from which it was carved determined the shape of the head. The distinctive way the face is represented, suggesting a heavily fleshed individual with a large somewhat downturned mouth, thick fleshy lips, a short, flat(ish) nose, and a wrinkled brow. The head seems to be wearing some kind of hat or helmet with incised and low-relief sculptural decorations. All signs point to male.

Meaning

There are multiple possible meanings. First the location, as one of four heads arranged facing outward from a central plaza, suggests it was part of an organized message. Several similar colossal heads in the same arrangement have been found at other Olmec sites. The iconography of the head seems might represent a ballplayer or a warrior wearing a helmet. It might also represent or symbolize a ruler; several heads = several rulers, perhaps a kind of geneology of rulership, and/or a protective function.

Context

The sculptural material, basalt, weighing on average 8 tons, was deliberately brought to the site from 60 miles away without the use of either a wheel or a large draught animal. The stone was worked with crude stone tools, as there is no metal in use at this time.

Ceremonial ax in the form of a maize god

Ceremonial ax in the form of a maize god:

Jadeite 11 1/2" high

found in

La Venta, Mexico

Olmec Culture

1200 BCE - 400 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The Olmec also placed paintings on cave walls, fashioned ceramic figurines, and carved sculptures in jade, a prized, extremely hard, dark-green stone they acquired from unknown sources far from their homeland. Sometimes the Olmec carved jade into ax-shaped polished forms that art historians call celts, which they then buried under their ceremonial courtyards or platforms, perhaps in connection with rites associated with maize agriculture. The celt shape could be modified into a figural form, combining relief carving with incising. Olmec sculptors used stone-tipped drills and abrasive materials, such as sand, to carve jade. The subjects represented include figures combining human and animal features and postures, such as the personified maize god illustrated here. The Olmec human-animal representations may also refer to the belief that religious practitioners underwent dangerous transformations to wrest power from supernatural forces and harness it for the good of the community."

Form

3-D sculptural form known as a celt, a type of stone handheld “blade” found in many stone-age cultures. Although jade is a hard enough stone to inflict damage and may have been used in warfare, it is more likely that the Olmec jade celts are ceremonial and symbolic. This celt has prominent facial features, which are not necessary to celts, and make it special.

Style

In addition to functional value, this object seems to represent some kind of hybrid human/animal figure. The style shares similarities with the colossal heads: especially the attention to the area of the lower face, mouth, lips and chin. Details are indicated by incised lines.

Meaning

The meaning is deducted by scholars from several features of the iconography. It has been likened to a crying baby and a “were-jaguar,” that is a shaman in the process of transformation from human to jaguar. It has also been identified as an early representation of the Maize-god. The god of agriculture in Meso-America. The fact of the location, deliberately buried with other jade celts and figurines in a pit, suggests its use in ceremony or sacrifice, or may be votive offerings to divine forces.

Context

The jade material in Meso-America is limited to jadeite; the green color seems to held symbolic value related to agriculture and vegetation, important signs of life force. The Olmec jade may have been obtained through trade routes linked to Guatemala, where jade quarries have been located, indicating that the Olmec did not live in cultural isolation.

Temple of the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl)

Temple of the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl)

:

Stone heads decorating the temple in the Ciudadela of Teotihuacan represent the Mesoamerican feathered-serpent god

found in

Teotihuacan, Mexico

Teotihuacan Culture

150 BCE - 600 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " At the south end of the Avenue of the Dead is the great quadrangle of the Ciudadela. It encloses a smaller pyramidal shrine datable to the third century CE, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, whom the Aztecs called Quetzalcoatl and worshiped as one of their major gods. The Aztecs associated Quetzalcoatl with wind, rain clouds, and life. The Teotihuacanos probably regarded him also as a war god. Beneath the temple, archaeologists found a tomb looted in antiquity, perhaps belonging to a Teotihuacano ruler. The discovery has led them to speculate that the Teotihuacanos buried their elite in or under pyramids, as did the Maya. Surrounding the tomb both beneath and around the pyramid were the remains of at least a hundred warriors. Some wore necklaces made of strings of human jaws, both real and sculpted from shell. As did most other Mesoamerican groups, the Teotihuacanos invoked and appeased their gods through human sacrifice. The presence of such a large number of sacrificed warriors reflects Teotihuacán’s successful militaristic expansion. Throughout Mesoamerica, the victors often sacrificed captured enemies. The temple’s sculptured panels, which feature projecting stone heads of the feathered serpent alternating with heads of a long-snouted scaly creature with rings on its forehead, decorate each of the temple’s six terraces. Representations of the feathered serpent go back to Olmec times, and his iconography is well established, but the scaly creature’s identity is unclear. Linking these alternating heads are low-relief carvings of feathered-serpent bodies and seashells. The shells reflect Teotihuacano contact with the peoples of the Mexican coasts and symbolize water, an essential ingredient for the sustenance of an agricultural economy. The Teotihuacanos also associated water with warfare and human sacrifice."

One of the most fascinating post-Olmec cultures of Mexico is the mysterious, once flourishing city of Teotihuacan located

in the Valley of Mexico on the outskirts of modern Mexico City. It is of supreme importance for

understanding the architectural development of the Maya and the Aztecs, as it reveals the earliest

complete city plan organized around plazas, raised ceremonial platforms, broad thoroughfares,

and pyramid temples- laid out on north/south east/west axes. Some of the earliest Meso-American

murals are found here.

A Secret Tunnel Found in Mexico May Finally Solve the Mysteries of Teotihuacan

Form

Stepped pyramid, broader at the base than tall, the third largest at Teotihuacan (the other two being the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon); characterized by wide, inhumanly steep central stairways, and projecting sculptural decoration.

Style

The three-dimensional projecting sculptural heads alternate two identical forms and styles: a geometric block-like form with goggle eyes, which has been identified as Tlaloc, the rain god, and a more readable, three-dimensional animal head surrounded by stylized petals or feathers, that has been identified as the “feathered serpent” or Quetzalcoatl, associated with water and life.

Meaning

The overwhelming presence of symbolic representations of water (shells and snakes) and traces of blue pigment suggest that this was an important temple dedicated to the gods in charge of rain and water sources.

Context

Later, when the Aztecs moved in to the Valley of Mexico, they discovered the ruins of Teotihuacan and gave the site its name. Teotihuacan collapsed at the end of the 3rd Century for unknown reasons; perhaps an extended period of extreme drought from which it never recovered. There is evidence of human sacrifice and warfare with the early Maya to the east. Wooden structures that would have been built atop some of the platforms did not survive.

Temple I (Temple of the Giant Jaguar)

Temple I (Temple of the Giant Jaguar)

:

145 ft pyramid, 9 tiers

found in

Tikal, Guatemala

Classic Maya Culture

250 CE - 900 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Temple I (also called the Temple of the Giant Jaguar after a motif on one of its carved wood lintels), reaches a height of about 145 feet. Considerable evidence indicates that the builders of Tikal, Palenque, and other Maya sites painted the exteriors of their temples red or red, white, and other bright colors. The Temple of the Giant Jaguar at Tikal is the temple-mausoleum of one of the city’s greatest rulers, Hasaw Chan K’awiil, who died in 732 CE. The Maya buried him in a vaulted chamber under the pyramid’s base. The towering (140 foot-high) structure consists of nine sharply inclining platforms—probably a reference to the nine levels of the Underworld (see “ The Underworld, the Sun, and Mesoamerican Pyramid Design ”)—and a three-chambered temple reached by a narrow stairway. Surmounting the temple is an elaborately sculpted roof comb, a vertical architectural projection that once bore the ruler’s gigantic portrait modeled in stucco."

The Maya, whose cultural region was east of the Valley of Mexico into the highlands and lowlands of Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize, went through several periods of development that have been identified by scholars as preclassic, classic, and post- classic. The 600 years of the Classic Maya culture were dominated by city-states whose rulers who were often at war with one another. Like the earlier cultures of Meso-America, the Maya built large public temple complexes, practiced human sacrifice, the ballgame, and many other features that we have come to know as typical of this region. Most importantly, the Maya developed an extensive, complex system of writing in the form of glyphs that have been translated to reveal a wealth of political and historical information about the Maya rulers and their obsession with legitimacy of rule and performing sacrificial rituals to ensure prosperity and the favor of the gods. The site that came to be known as Tikal in the 19th century, after its re-discovery, is one of the oldest and most important of Maya cities.

Form

Stepped pyramid of 9 levels, taller than wide, with extremely steep and high stairways; the top is covered with a square structure topped with what has been called, descriptively, a “roof comb” that once bore the likeness of the ruler modeled in stucco. Royal burials under the pyramid make it a temple-mausoleum, like Angkor Wat. All Maya temples were plastered and painted in bright colors.

Style

The proportions and details are unique to Tikal.

Meaning

Temple-mausoleum in honor of the ruler, Hasaw Chan K’awiil, d. 732.

Context

The collapse of the Maya is another mystery. It may have been a combination of environmental and man-made factors: warfare, climate change, famine, etc.

Shield Jaguar and Lady Xoc

Shield Jaguar and Lady Xoc

:

Limestone, 3' 7" x 2' 6 1/2"

found in

Yaxchilan, Mexico

Classic Maya Culture

250 CE - 900 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Elite women played an important role in Maya society, and some surviving artworks document their high status. The painted reliefs on the lintels of Temple 23 at Yaxchilán represent an elite woman as a central figure in Maya ritual. Lintel 24 depicts the ruler Itzamna B’ahlam II (r. 681–742 CE), known as Shield Jaguar, and his principal wife, Lady Xoc. She is magnificently outfitted in an elaborate woven garment, headdress, and jewels. With a barbed cord, she pierces her tongue in a bloodletting ceremony that, according to accompanying inscriptions, celebrated the birth of a son to one of the ruler’s other wives as well as an alignment between the planets Saturn and Jupiter. The celebration must have taken place in a dark chamber or at night because Shield Jaguar provides illumination with a blazing torch. These ceremonies induced an altered state of consciousness in order to connect the bloodletter with the supernatural world. (Lintel 25 depicts Lady Xoc and her vision of an ancestor emerging from the mouth of a serpent.)"

This sculpture is a fine example of the high quality and sophistication of Maya art, much of which, particularly painting,

unfortunately, has been lost to time and destruction. It is also rich in information about Maya

culture and ritual as well as ideas of what is beautiful.

Form

High-relief stone sculpture - a stone lintel, an architectural member placed over a doorway. Narrative image.

Style

Stylized naturalism. The human figures represented here are typical in their proportions and details of Maya art throughout the empire, which suggests some kind of centralized art or image making authority. Compare the style of the figures and the treatment of space to the figures painted on Maya ceramics, such as the cylinder vase illustrated in figure 18-13. Some common characteristics: large heads with bulging eyes, large noses and sharply angled foreheads (the result of shaping the heads of Maya infants); short necks, broad shoulders, thick, fleshy, bodies and limbs. The designer of the scene was concerned with accurately depicting multiple details of costume, hairstyles, head-gear, jewelry and fabric. The effect of the overall design allows the viewer to appreciate a scene of two prominent figures in a shallow space mutually engaged in an activity. Notice how the designer found a harmonious way to include the relevant glyphs.

Meaning

The kneeling woman, the wife of the ruler and an important person in her own right, is drawing a thorned rope through a hole in her tongue. The blood that falls from her lips is collected on papers in the offering plate at her knee. These will later be burned for the gods. Standing before her, his legs spread to better support the weight of the burning torch he holds over her head, is her husband, the ruler of Yaxchilan citystate. What additional information about this scene is located in the text?

Context

Considering what great importance was placed on hereditary lineages in the Maya kingdom, this demonstration of a birth celebration,

ensuring an heir, is part of the political propaganda of the ruler. It also underscores the high

place of females in Maya royal society. Examine, for example, the reproductions of the Maya murals

found at Bonampak (figures 16-1a- c).

On Bonampak watch: The

Splendid Maya Murals of Bonampak, Mexico, with Prof. Mary Miller, Yale University:

The Splendid Maya Murals of Bonampak, Mexico, with Prof. Mary Miller

Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt)

Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt):

Anedesite 11'6" high

found in

Tenochtitlan, Mexico City

Aztec Culture

1300 CE - 1521 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " In addition to relief carving, the Aztecs produced freestanding statuary. The most impressive surviving example is the colossal statue of the beheaded Coatlicue discovered in 1790 near Mexico City’s cathedral. The sculpture’s original setting is unknown, but some scholars believe that it was one of a group set up at the Great Temple. The main forms are in high relief, the details executed either in low relief or by incising. The overall aspect is of an enormous blocky mass, its ponderous weight looming over awestruck viewers. From the beheaded goddess’s neck writhe two serpents whose heads meet to form a tusked mask. Coatlicue wears a necklace of severed human hands and excised human hearts. The pendant of the necklace is a skull. Entwined snakes form her skirt. From between her legs emerges another serpent, symbolic perhaps of both menses and the male member. Like most Aztec deities, Coatlicue has both masculine and feminine traits. Her hands and feet have great claws. All her attributes symbolize sacrificial death. Yet, in Aztec thought, this mother of the gods combined savagery and tenderness, for out of destruction arose new life, a theme seen earlier at Teotihuacán."

After the Maya, the Aztec (aka. Mexica) are the next great culture and civilization in Mexico and the one that had the great misfortune of encountering European conquerors intent on enriching themselves and their sponsoring countries with the indigenous wealth of the new world. The great Aztec civilization, with its magnificent capital at Tenochtitlan (now beneath modern Mexico City), was totally decimated by the Spanish conquistadors under the leadership of Hernan Cortez (Cortes) in 1521. The story of the founding of the Aztec Empire by a wandering group of indigenous peoples searching for a homeland prophesized by their god, Huitzilopochtli, the hummingbird god of war. This they discovered on an island in Lake Texcoco, which grew into the amazing city of Tenochtitlan. Aztec art and culture, which shares the many features of its predecessors: pyramid temples, plazas, painting and sculpture, and human blood sacrifices, nevertheless developed a unique iconography and styles of their own.

Form

Freestanding, giant 3-D sculpture in andesite stone. Identified as a representation of the goddess, Coatlicue,

the mother of many gods and goddesses. The photograph only shows the front side of the image,

which is much more complicated when viewed in-the-round.

Please watch

the video conversation with Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker discussing the iconography

and form:

Coatlicue

Style

The treatment of the form is blocky, a kind of “brutal naturalism” (my term), that is typical of surviving Aztec artwork, especially sculptural forms. For example the treatment of the human hands is so tender and sensitive, they appear “soft” and fleshy like real hands; yet other details are more simplified patterns and shapes.

Meaning

The image may represent the beheading of Coatlicue by her daughter, Coyalxauhqui, a mythological matricide born out of jealousy.

Context

This is only one of several monumental stone sculptures that once stood in the plaza in front of the Great Temple complex of Tenochtitlan. Because of its fearsome qualities it was buried by the Spanish, rediscovered in the late 18 th century and rapidly reburied, and finally excavated permanently in the early 19 th century.

Coyolxauhqui (She of the Golden Bells)

Coyolxauhqui (She of the Golden Bells):

Stone diameter 10' 10"

found in

Tenochtitlan, Mexico City

Aztec Culture

1300 CE - 1521 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The Temple of Huitzilopochtli at Tenochtitlán commemorated the god’s victory over his sister and 400 brothers, who had plotted to kill their mother, Coatlicue. The myth signifies the birth of the sun at dawn, a role that Huitzilopochtli sometimes assumed, and the sun’s battle with the forces of darkness, the stars and moon. Huitzilopochtli killed or chased away his brothers and dismembered the body of his sister, the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui, at Coatepec Mountain near Tula (symbolized by the pyramid itself). The mythical event is the subject of a huge stone disk, whose discovery in 1971 set off the ongoing archaeological investigations in the Zócalo. The Aztecs placed the relief at the foot of the staircase leading up to one of Huitzilopochtli’s earlier temples on the site. (Cortés and his army never saw the disk because it lay within the outermost shell of the Great Temple.) The relief presents the image of the murdered and segmented body of Coyolxauhqui. The mythological theme also carried a contemporary political message. The Aztecs sacrificed their conquered enemies at the top of the Great Temple and then hurled their bodies down the temple stairs to land on this stone. The victors thus forced their foes to reenact the horrible fate of the dismembered goddess. The Coyolxauhqui disk is a superb example of art in the service of state ideology. The unforgettable image of the fragmented goddess proclaimed the power of the Mexica over their enemies and the inevitable fate that must befall their foes when defeated. Marvelously composed, the relief has a kind of dreadful beauty. Within the circular space, the design’s carefully balanced, richly detailed components have a slow turning rhythm reminiscent of a revolving galaxy. The carving is in low relief, a smoothly even, flat surface raised from a flat ground. It is the sculptural equivalent of the line and flat tone, the figure and neutral ground, characteristic of Mesoamerican painting."

The fierce, warlike Aztec People, who called themselves the Mexica, wandered into the Valley of Mexico from the north around

1250 CE and settled on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. They established a powerful empire

based on the allegiances of numerous surrounding groups and expanded their power from coast to

coast. Like the Olmec and Maya before them, they practiced human sacrifice and built elaborate

ceremonial plaza and temples to their gods. Their end came with the arrival of Hernan Cortes

and his army of Spanish mercenaries in the early 16th Century.

Secret of Nazca Lines - Documentary

Form

High-relief monumental stone sculpture in the form of a thick, round disc depicting the dismembered goddess, Coyolxauhqui, as the moon goddess.

Style

Compare with Coatlicue; a relief version of the Aztec 3-D sculptural style. The head is in profile, the torso is twisted at the waist making the upper half of the body appear frontally, and the lower half in profile (a similar representational device was used by the ancient Egyptians). Brutal naturalism? The torso and severed limbs are arranged within a circle and represent the phases of the moon. Like all Aztec sculpture, this was originally painted in simple pigments of red, yellow, blue.

Meaning

According to one Mixtec legend Coyolxauhqui became frustrated with her mother’s endless production of progeny, and upon learning that she was pregnant again, decided to end it by killing her. With the help of some of her brothers she succeeded in decapitating Coatlicue, but instead of succeeding in destroying her mother, she released the soon to be birthed Huitzilopochtli, also known as the sun god, who emerged from her neck and cut his sister into a “million” pieces.

Context

The location of the colossal stone disc at the foot of the sacrificial stairway of the Temple Major, suggests that sacrificial victims, whose hearts were cut out at the top of the temple, were then thrown down the stairs and butchered on this stone.

Raimondi Stele

Raimondi Stele:

Green diorite 6' high

found in

Chavin de Huantar, Peru

Chavin Culture

900 BCE – 250 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

"Found in the main temple at Chavín de Huántar and named after its discoverer, the Raimondi Stele represents a figure called

the “staff god.” He appears in various versions from Colombia to northern Bolivia, but always

holds staffs. Seldom, however, do the representations have the degree of elaboration found at

Chavín. The Chavín staff god gazes upward, frowns, and bares his teeth. His elaborate headdress

dominates the upper two-thirds of the slab. Inverting the image reveals that the headdress consists

of a series of fanged jawless faces, each emerging from the mouth of the one above it. Snakes

abound. They extend from the deity’s belt, make up part of the staffs, serve as whiskers and

hair for the deity and the headdress creatures, and form a braid at the apex of the composition.

The Raimondi Stele clearly illustrates the Andean artistic tendency toward both multiplicity

and dual readings. Upside down, the god’s face turns into two faces. The ability of gods to transform

before viewers’ eyes is a core aspect of Andean religion. Chavín iconography spread widely throughout

the Andean region via portable media such as goldwork, textiles, and ceramics. For example, more

than 300 miles from Chavín on the south coast of Peru, archaeologists have discovered cotton

textiles with imagery recalling Chavín sculpture. Painted staff-bearing female deities, apparently,

local manifestations or consorts of the highland staff god, decorate these large cloths, which

may have served as wall hangings in temples. Ceramic vessels found on the north coast of Peru

also carry motifs similar to those found on Chavín stone carvings."

We begin our introduction to the pre-Conquest cultures of Peru with the Chavin, roughly cotemporaneous with the late Olmec,

and situated in the Andes highlands. Although they are not the earliest Peruvian culture identified,

their sites are the first to reveal monumental public artwork of high sophistication, like the

so-called Raimondi Stele. Explore:

Chavín de Huántar

Exploring Chavin de Huantar

Unraveling the Mystery behind the Raimondi Stele

Form

Granite stele (stela), highly polished. Flat standing monument (like a tombstone). Low relief carving of a figure holding ritual objects in both hands and wearing an elaborate headdress.

Style

The style of depiction, flat and linear, with emphasis on silhouettes and carved away ground, is reminiscent of styles and motifs, like the snake belts and the claw feet, that we have seen in Meso-America, yet with a flavor and a unique iconography.

Meaning

This strange figure, frontally represented and holding tall bundles at its side, reappears in Andean culture in a number of forms, and has been called, for lack of a better understanding, “the staff-god.” If you look closely you can detect that the images is “readable” from two directions, in a device known as “contour rivalry.” Do you see? contour rivalry.” Do you see?

Context

This is clearly a sacred object, seemingly kept outside the temple in the courtyard, but its meaning and use is unknown. See also the so-called, mysterious Lanzon Stele from the same site.

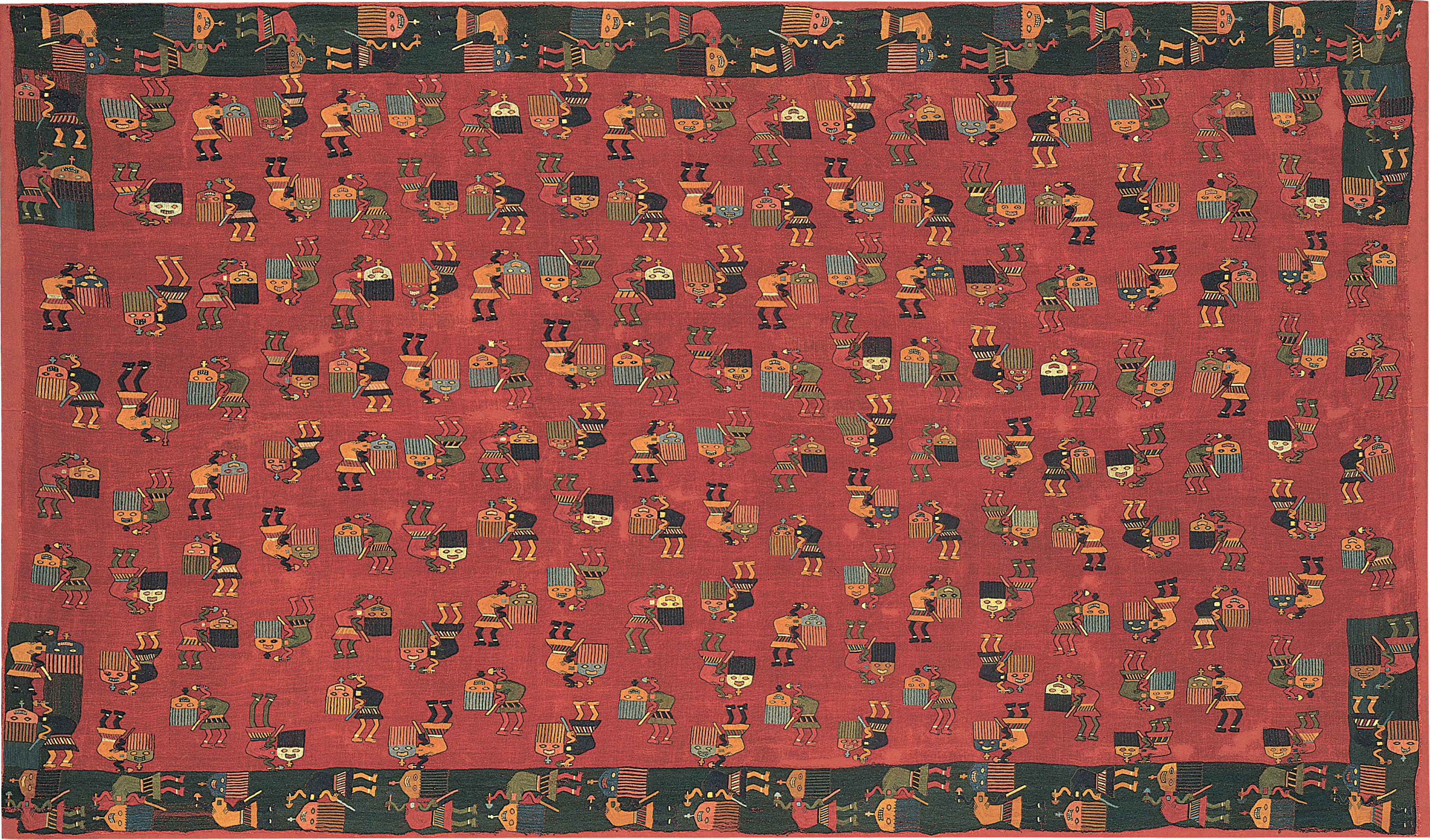

Embroidered Funerary Mantle

Embroidered Funerary Mantle:

Plain-weave camelid fiber with stem-stitch embroidery of camelid wool, 4' 7/8" x 7' 10 7/8"

found in

Paracas Peninsula, Peru

Paracas Culture

800 BCE - 100 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The dry deserts of coastal Peru have preserved not only numerous textiles from different periods but also hundreds of finely worked baskets containing spinning and weaving implements. These tools are invaluable sources of information about Andean textile production processes. The baskets found in documented contexts came from women’s graves, attesting to the close association between weaving and women, the reverence for the cloth-making process, and the Andean belief that textiles were necessary in the afterlife. A special problem all weavers confront is that they must visualize the entire design in advance and cannot easily change it during the weaving process. No records exist of how Andean weavers learned, retained, and passed on the elaborate patterns they wove into cloth, but some painted ceramics depict weavers at work, apparently copying designs from finished models. However, the inventiveness of individual weavers is evident in the endless variety of colors and patterns in preserved Andean textiles. This creativity often led Andean artists to design textiles that are highly abstract and geometric. Paracas embroideries, for example, may depict humans, down to the patterns on the tunics they wear, yet the weavers reduced the figures to their essentials in order to focus on their otherworldly role. The Wari compositions are the culmination of this tendency toward abstraction in which figural motifs become stunning blocks of color that overwhelm the subject matter itself."

The Paracas culture was found on the south coast of Peru. They produced ceramics and textiles of great beauty, which have

survived due to the dryness of the desert coast sand where they were used to wrap the dead for

pit chamber burial. The multiple weaving techniques invented by (presumably) Paracas women, are

astounding in their fineness and complexity, achieving a kind of 3-dimensional sculptural effect

both with and without the use of a loom and with wool embroidery.

The Paracas Textile<

Form

Rectangular woven mantle, blanket

Style

Design is a repetitive pattern of “flying shamans” or dancing shamans holding severed heads.

Meaning

Journey to the spirit world

Context

Such mantles were woven with great love by daughters for mothers; some may have been precious objects of wardrobe that were

then buried with the dead. The mantles served as wrapping for the body of the deceased; between

layers small mementos and charms were slipped in. The finished bundle resembled a large round

egg. This was then slipped into the burial chamber deep in the sand. See photos:

Paracas burials

Hummingbird

Hummingbird:

Dark layer of pebbles scraped aside to reveal lighter clay and calcite beneath

found in

Nasca Plain, Peru

Nasca Culture

200 BCE - 600 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Some 800 miles of lines drawn in complex networks on the dry surface of the Nasca Plain have long attracted world attention because of their colossal size, which defies human perception from the ground. Preserved today are about three dozen images of birds, fish, and plants, including a hummingbird several hundred feet long. The Nasca artists also drew geometric forms, such as trapezoids, spirals, and straight lines running for miles. The Nasca produced these “Nasca Lines,” as art historians have dubbed their immense earth drawings, by selectively removing the dark top layer of stones to expose the light clay and calcite below. Artisans created the lines quite easily from available materials and using rudimentary geometry. Small groups of workers have made modern reproductions of them with relative ease. The lines seem to be paths laid out using simple stone-and-string methods. Some lead in traceable directions across the deserts of the Nasca River drainage. Others have many shrinelike nodes punctuating the lines, like the knots on a cord. Some lines converge at central places usually situated close to water sources and seem to be associated with water supply and irrigation. They may have marked pilgrimage routes for those who journeyed to local or regional shrines on foot. Altogether, the vast arrangement of the Nasca Lines is a system—not a meaningless maze but a traversable map that plotted the whole terrain of Nasca material and spiritual concerns. Remarkably, until quite recently, the peoples of highland Bolivia made and used similar ritual pathways in association with shrines, demonstrating the tenacity of indigenous Andean belief systems."

The Nasca Culture, located south of the Paracas area on a plateau along the coast, is famous for its unique artifact: monumental

line “drawings” in the earth that are only visible from the air. Known as the Nasca Lines these

include birds, animals, and Watch National Geographic documentary:

Secret of Nazca Lines - Documentary

Form

Simple outline representational shapes made by removing a top layer of stones to reveal the ground beneath; this creates a sense of light lines on a dark ground.

Style

The style, or matter or representation remains consistent figure after figure suggesting a highly organized and controlled system of production.

Meaning

Unknown, although there are many theories. What is one of these?

Context

Reveals well organized society with collective projects cooperatively executed. Significant enough to the people to warrant such long term and persistent efforts.

Vessel in shape of a portrait head

Vessel in shape of a portrait head:

Painted clay, 1' 1/2" high

found in

Moche, Trujillo, Peru

Moche Culture

100 BCE - 700 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Among the most famous art objects, the ancient Peruvians produced are the painted clay vessels of the Moche, who occupied

a series of river valleys on the north coast of Peru around the same time that the Nasca flourished

to the south. Moche ceramics rival those of the Greeks and the Maya not only in quality but also

in the amount of information they convey about Moche society. Moche pots illustrate architecture,

metallurgy, weaving, the brewing of chicha (fermented maize beer), human deformities and diseases,

and even sexual acts. Moche vessels are predominantly flat-bottomed stirrup-spouted jars derived

from Chavín prototypes. The potters generally decorated them with a bichrome (two-color) slip.

Although the Moche made early vessels by hand without the aid of a potter’s wheel, they fashioned

later ones in two-piece molds. Thus numerous near-duplicates exist today. Moche potters continued

to refine the stirrup spout, making it an elegant slender tube, much narrower than the Chavín

examples. The portrait vessel illustrated here is an elaborate example of a common Moche type.

It may depict the face of a warrior, a ruler, or even a royal retainer whose image may have been

buried with many other pots to accompany his dead master into the afterlife. The realistic rendering

of the physiognomy is particularly striking. Some Moche portrait vessels appear to depict the

same individual at different ages. These figures must have been members of elite Moche families,

whose features the ceramists recorded repeatedly, beginning in childhood."

The Moche Culture deserves special study. The artifacts revealed from Moche sites are uniquely styled, of unparalleled variety,

and utterly fascinating. Please explore: (viewer discretion advised)

The Lost Civilisation of Peru

moche pottery

The so-calledportrait-head drinking vessels represent a large class of Moche pottery. These were

likely created for drinking a kind of beer.

Form

Stirrup Vessel in the shape of a human head wearing an elaborate hat. Stirrup vessels allow for air to escape during the drinking process, releasing the vacuum that would otherwise occur when the spout is sipped from. Painted pottery.

Style

Naturalism, possibly even portrait realism.

Meaning

Amusement? Honoring an individual?

Context

Found in burials.

Ear ornament

Ear ornament:

Gold and turquoise 4' 4/5" diameter

found in

Tombs of the Lords of Sipan, Peru

Moche Culture

100 BCE - 700 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " An ear ornament of turquoise and gold found in one Sipán tomb shows a warrior priest clad much like the Lord of Sipán. Two retainers appear in profile to the left and right of the central figure. Represented frontally, he carries a war club and shield and wears a necklace of owl-head beads. The figure’s bladelike, crescent-shaped helmet is a replica of the large gold one buried with the Sipán lord. The war club and shield also match finds in the Warrior Priest’s tomb. The figure wears an ear ornament that is a simplified version of the ornament it decorates. Other details also correspond to excavated objects—for example, the removable nose ring hanging down over the mouth. The value of the Sipán find is incalculable for what it reveals about elite Moche culture and for its confirmation of the accuracy of the iconography of Moche artworks."

The Moche built pyramid temple/mausoleums out of adobe, which has eroded badly since their defeat by the Spanish in the

17th Century. There is an abundance of archaeological materials from the site of Sipan: gold,

silver, and copper jewelry and ornaments; murals, ceramics, human and animal sacrifices; necklaces,

ear-spools, large nose rings and numerous fabrics. The narrative scenes from Moche life and warfare

reveal brutal blood-letting rituals and human sacrifices. No written language.

The Lord of Sipan

Form

Ear-spool (earring/ear ornament). Gold disc embellished with turquoise and 3- dimensional representation of a warrior king (with moving parts) wearing large ear- spools and the kind of weapons and jewelry found in the burial.

Style

The figure style is characteristic of a convention (way of representation) that is found throughout all forms of Moche art, especially narrative scenes: large heads, broad shoulders, small lower body proportions. Stylized proportions faces, large distinctly shaped eyes.

Meaning

Sign of rank and power: a large figure of a ruler/priest flanked by warrior attendants smaller in size.

Context

Object of rank and luxury sent with the deceased into the next life.

Remains of the Temple of the Sun (aka. The Wall of the Golden Enclosure)

Remains of the Temple of the Sun (aka. The Wall of the Golden Enclosure):

Gold, Silver, and emeralds covered the temple's interior walls

found in

Cuzco, Peru

Inka Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

One Inka building at Cuzco that survives in small part is the Temple of the Sun, built of ashlar masonry (stone blocks fit

together without mortar), an ancient construction technique that the Inka had mastered. Cuzco

masons laid the stones with perfectly joined faces. Remarkably, the Inka produced the close joints

of their masonry by abrasion alone, grinding the surfaces to a perfect fit. The stonemasons usually

laid the blocks in regular horizontal courses. Inka builders were so skilled that they could

fashion walls with curved surfaces, their planes as level and continuous as if they were a single

form. The surviving walls of the Temple of the Sun are a prime example of this single-form effect.

On the exterior, for example, the stones, precisely fitted and polished, form a curving semiparabola.

The Inka set the ashlar blocks for flexibility during earthquakes, allowing for a temporary dislocation

of the courses, which then return to their original position. Known to the Spanish as Coricancha

(Golden Enclosure), the Temple of the Sun was the most magnificent of all Inka shrines. The 16th-century

Spanish chroniclers wrote in awe of Coricancha’s splendor, its interior veneered with sheets

of gold, silver, and emeralds and housing life-size statues of silver and gold. Nothing survives,

but some preserved Inka statuettes may suggest the appearance of the lost large-scale statues.

Built on the site of the home of Manco Capac, son of the sun god and founder of the Inka dynasty,

the Temple of the Sun housed mummies of some of the early rulers. Dedicated to the worship of

several Inka deities, including the creator god Viracocha and the gods of the sun, moon, stars,

and the elements, the temple was the center point of a network of radiating sight lines leading

to some 350 shrines, which had both calendar and astronomical significance."

The Inka were the last of the great Peruvian kingdoms and cultures. The destruction of the Inka by the Spanish under Francisco Pizarro represents another chapter in the conquest and pillaging of the new world by European soldiers of fortune. The Temple of the Sun (god), Viracocha, was part of a large ceremonial and astronomical structure called the Coricancha. After the conquest of the Inkas, the murder of their king, Atawalpa, and the destruction of the Coricancha a church, Santo Domingo and convent was build on top of the stone remains.

Form

Masonry, called ashlar masonry, stones are fitted and cut to perfection and placed without mortar. An incredible sloping wall section speaks to the skill of the masons.

Style

Ashlar masonry

Blood and Flowers-In search of the Aztecs (Documentary)

Meaning

The Coricancha as a multi-function royal administrative, religious, scientific center. It was decorated with gold and silver sheets and sculptures that defied the imagination. The mummified bodies of the Inka ancestors were kept there and cared for in elaborate rituals.

Context

The Inka/Inca, despite the absence of wheeled vehicles and a written language, was a high civilization, a true empire, with a capital at Cusco, and a royal religious center high in the Andes at Machu Picchu (which was re-discovered by Hiram Bingham in 1911).

Pipe

Pipe:

Stone 8" high

found in

Ohio/ Kentucky Area

Adena Culture

1000 BCE - 200 BCE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Archaeologists have found remains of the Adena culture of Ohio at about 500 sites in the Central Woodlands. The Adena buried

their elite in great earthen mounds and often placed ceremonial pipes in the graves. Smoking

was an important social and religious ritual in many Native American cultures and pipes were

treasured status symbols that men wanted to take with them into the afterlife. The Adena pipe

shown here, carved between 500 BCE and the end of the millennium, takes the shape of a standing

man. The figure has naturalistic joint articulations and musculature, a lively flexed-leg pose,

and an alert facial expression—all combining to suggest movement. In form and costume (note the

prominent ear spools), the figure resembles some Mesoamerican sculptures."

The Adena Culture of Ohio, one of the early Mound Builders, left behind burial mounds that have revealed numerous small-scale stone sculptures, particularly tobacco pipes.

Form

Tobacco pipe in human form.

Style

Stylized naturalism; emphasis on head, musculature, animation, and functionality.

Meaning

Status symbol; perhaps it represents a warrior.

Context

Probably used in life and buried with the deceased as a personal treasure.

Serpent Mound

Serpent Mound:

1200' long, 20' wide, 5' high

found in

Ohio Brush Creek, Adams County, Ohio

Mississippian Culture

800 CE - 1500 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Serpent Mound is one of the largest and best known of the Woodlands effigy mounds, but it is the subject of considerable

controversy. First excavated in the 1880s, Serpent Mound represents one of the first efforts

at preserving a Native American site from destruction at the hands of pot hunters and farmers.

For a long time after its exploration, archaeologists attributed construction of the mound to

the Adena culture, which flourished in the Ohio area during the last several centuries BCE. Radiocarbon

dates taken from the mound, however, indicate that the people known as Mississippians built it

much later. Unlike most other ancient mounds—for example, Monk’s Mound in Cahokia, Illinois—Serpent

Mound contained no evidence of burials or temples. Serpents, however, were important in Mississippian

iconography, appearing, for instance, etched on shell gorgets similar to the one reproduced in

Fig. 18-32 . The Mississippians strongly associated snakes with the earth and the fertility of

crops. A stone figurine found at one Mississippian site depicts a woman digging her hoe into

the back of a large serpentine creature whose tail turns into a vine of gourds. Some researchers

have proposed another possible meaning for the construction of Serpent Mound. The date suggested

for it is 1070, not long after the brightest appearance in recorded history of Halley’s Comet

in 1066, an astronomical event recorded on the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry as an important omen.

Could Serpent Mound have been built in response to the same comet lighting up the North American

heavens? Scholars have even suggested that the serpentine form of the mound replicates Halley’s

Comet streaking across the night sky. Whatever its meaning, an earthwork as large and elaborate

as Serpent Mound could only have been built by a large labor force under the firm direction of

a powerful elite eager to leave its mark on the landscape forever."

Mississippian Culture covered a large swath of the Ohio and Mississippi river drainage areas in the American Midwest. The Serpent Mound is one of the largest of these Woodland cultures to survive.

Form

Effigy Mound. A raised mound in the form of a long, slender, undulating snake, 1200 ft in length, whose open jaws appear to be holding an egg and whose tail forms a tight spiral. Or, alternately, the path of Halley’s Comet (1066).

Style

Like the Nasca Lines of Peru, the form is best readable from the air.

Meaning

Perhaps connected to astronomical events, otherwise unknown.

Context

The exquisitely rendered large-scale product of a highly organized and intentional society.

Bowl

Bowl:

Painted ceramic, diameter 1' 1/2"

found in

Mimbres, New Mexico

Mimbres Culture

1000 CE - 1250 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

The Mimbres culture of southwestern New Mexico, which flourished between approximately 1000 and 1250 CE, is renowned for

its black-on-white painted bowls. Mimbres bowls have been found in burials under house floors,

inverted over the head of the deceased and ritually “killed” by puncturing a small hole at the

base, perhaps to allow the spirits of the deceased to join their ancestors in the sky (which

contemporary Southwestern peoples view as a dome). The bowl illustrated here dates to around

1250 and features an animated graphic rendering of two black cranes on a white ground. The contrast

between the bowl’s abstract border designs and the birds creates a dynamic tension. Thousands

of different compositions appear on Mimbres pottery. They range from lively and complex geometric

patterns to abstract renditions of humans, animals, and composite mythological beings. Almost

all are imaginative creations by artists who seem to have been determined not to repeat themselves.

Their designs emphasize linear rhythms balanced and controlled within a clearly defined border.

Because the potter’s wheel was unknown in the Americas, the artists constructed their pots out

of coils of clay, creating countless sophisticated shapes of varied size, always characterized

by technical excellence. Although historians have no direct knowledge about the potters’ identities,

the fact that pottery making was usually women’s work in the Southwest during the historical

period (see “ Gender Roles in Native American Art ”) suggests that the Mimbres potters also may

have been women."

The Mimbres culture (a subdivision of Mogollon culture) of southwest New Mexico is best known for fine black/brown painted

bowls found in burial chambers beneath house floors. These bowls have been ritually “killed.”

mimbres bowls

The Archaeology and Meaning of Mimbres

Form

A large broad, flattish bowl.

Style

Finely potted with smooth surfaces; painted with narrative scenes or geometric designs characterized by careful symmetry.

Meaning

“Killed” bowls were placed over the face of the deceased perhaps to release the spirit of the bowl/deceased; perhaps to signify death as a kind of finality.

Context

Mimbres custom; bowls are used and then destroyed at time of death and burial.

Eagle Transformation Mask (open and closed)

Eagle Transformation Mask (open and closed):

Wood, feathers, and strinf 1' 10" x 11"

found in

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Kwakwaka’wakw (formerly Kwakiutl) Culture

1800 CE - 1900 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Like so many objects produced by Native Americans through the centuries, the masks fashioned by Northwest Coast artists were

not created as display pieces but for use in sacred rituals, especially those concerned with

healing. Kwakwaka’wakw religious specialists, for example, wore masks in dramatic public performances

during the winter ceremonial season. The animals and mythological creatures represented in masks

and a host of other carvings derive from the Northwest Coast’s rich oral tradition and celebrate

the mythological origins and inherited privileges of high-ranking families, who trace their lineage

to mythic animals or composite human-animals. The artist who made the Kwakwaka’wakw mask illustrated

here meant it to be seen in flickering firelight, and ingeniously constructed it to open and

close rapidly when the wearer manipulated hidden strings. He could thus magically transform himself

from human to eagle and back again as he danced. The transformation theme, in myriad forms, is

a central aspect of the art and religion of the Americas. The Kwakwaka’wakw mask’s human aspect

also owes its dramatic character to the exaggeration and distortion of facial parts—such as the

hooked beaklike nose and flat, flaring nostrils—and to the deeply undercut curvilinear depressions,

which form strong shadows. In contrast to the carved human face, but painted in the same colors,

is the two-dimensional abstract image of the eagle painted on the inside of the outer mask."

Transformation masks

Kwakiutl Ceremonial Dance

Form

Mask worn in ritual dance; in the form of an Eagle when closed and revealing a human/eagle face when open. Details painted in red, blue, white and black; feathers and string.

Style

Style of Northwest Coast: Haida, etc.: stylized forms of animal parts, almost like a visual language. Exaggeration, distortion, abstraction: forms, reduced to elemental symbols.

Meaning

Assists the official spiritual performer accomplish the task of the ritual; a kind of magic trick to suggest change and transformation.

Context

Shamanistic religious traditions. Please note: this artifact is an example of imperfect or incomplete retrieval. The practice of taking only part of an object of ethnographic interest and leaving behind the rest, either through ignorance of the meaning of the artifact, or deliberate aesthetic choice.

Chilkat Blanket

Chilkat Blanket:

Mountain goat wool and cedar bark 6' x 2' 11"

found in

Between Alaska and British Columbia, Portland Canal

Tlingit Culture

1800 CE - 1900 CE

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Another characteristic Northwest Coast art form is the Chilkat blanket, named for an Alaskan Tlingit village. Male designers

provided the templates for these blankets in the form of wood pattern boards for female weavers.

Woven of shredded cedar bark and mountain goat wool suspended from a single bar instead of on

a loom, the Tlingit blankets took at least six months to complete. These blankets, which served

as robes worn over the shoulders, became widespread prestige items of ceremonial dress during

the 19th century. They display several characteristics of the Northwest Coast style recurrent

in all media: symmetry and rhythmic repetition, schematic abstraction of animal motifs (a bear

in the illustrated robe), eye designs, a regularly swelling and thinning line, and a tendency

to round off corners."

The Artistry of Tlingit Weaving

Form

A shoulder mantle or apron worn by a shaman, priest, healer, dancer in the Tlingit culture.

Style

Similar to the transformation mask above: the abstract forms are a visual vocabulary that tells stories related to myths and ancestors. Symmetry, repetition, abstraction.

Meaning

Family designs passed on from generation to generation.

Context

Public, social, religious/spiritual events of community significance.