Africa | Study Guide Images

View the study guide images for this region. You can access each study guide image and its information by clicking on the corresponding tab. Feel free to rearrange the tabs by clicking and dragging them over one another. Click on the menu icon to reset the accordion. Hovering over the menu icon allows you to navigate to a study guide image you wish to see.

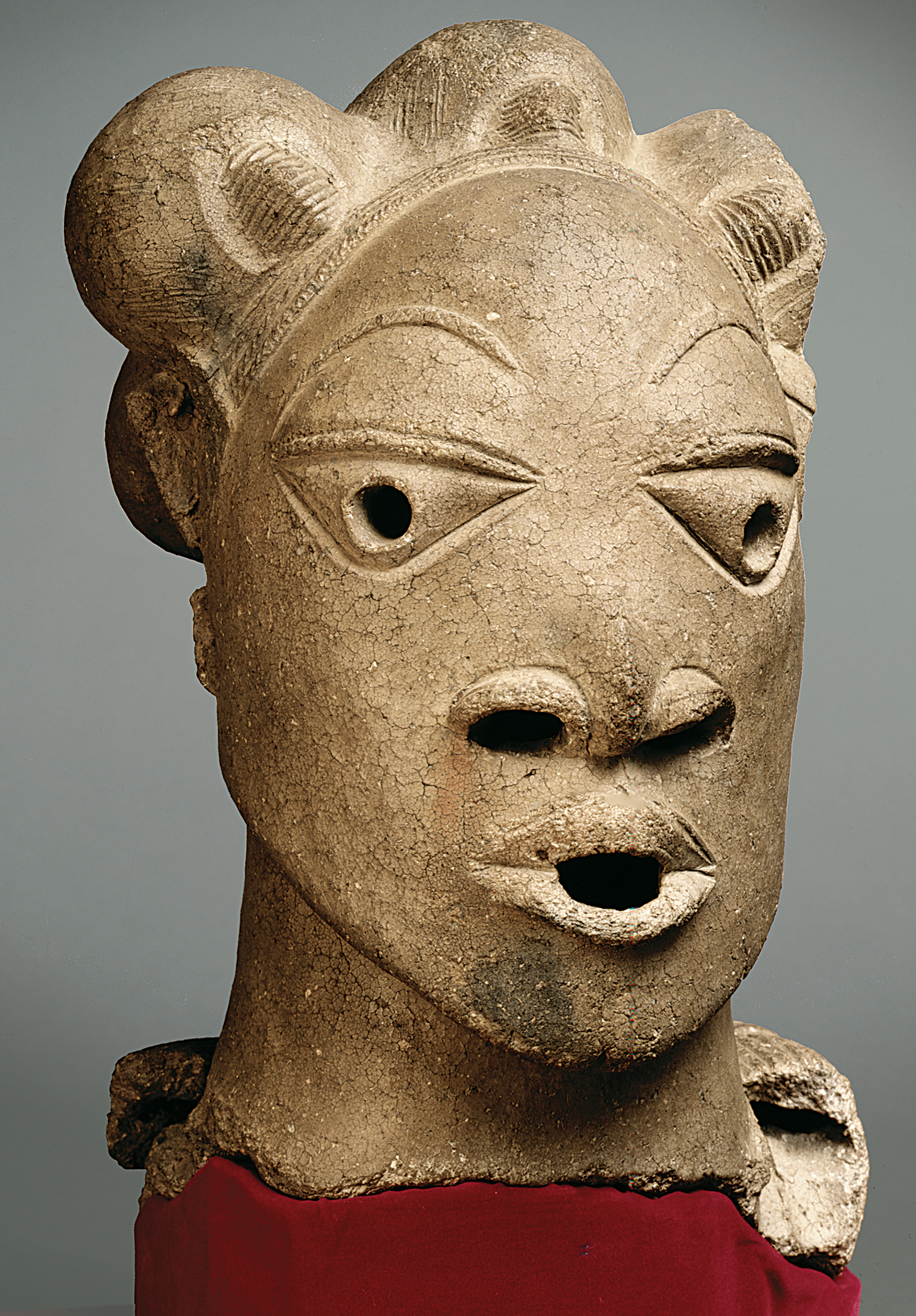

Nok head

Nok head:

Terracotta, 1′ 2 3/16″ high

Rafin Kura, Nigeria

Nok Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Scholars disagree on whether the Nok sites were unified politically or socially, but it is certain that the people of this region lived in villages, engaged in farming, and also knew how to mine and smelt iron ore. Hundreds of Nok-style human and animal heads, body parts, and figures have been found accidentally during modern tinmining operations or washed up after especially heavy storms, but unfortunately, the original context of none of the finds is known. All, however, can be dated broadly between 500 BCE and 200 CE. A representative Nok terracotta head, found at Rafin Kura, is a fragment of what was originally a full figure. Preserved fragments of other statues indicate that the Nok sculptors fashioned a variety of types, including standing, seated, and kneeling figures. As in the much later Benin plaque and African art in general, the heads are disproportionately large compared with the bodies. The head shown here has an expressive face with large triangular eyes beneath arched eyebrows, flaring nostrils, parted lips, and a coiffure divided into tufted sections. The pierced pupils, mouth, and ear holes are characteristic of Nok sculpture and served as air vents, helping to equalize the heating of the hollow clay head during the firing process. The incised grooves in the hair and other engraved details suggest that the sculptor carved some features of the head after removing the terracotta sculpture from the kiln. The function of the Nok terracottas is unclear, but the broken tube around the neck of the Rafin Kura figure may be a bead necklace, an indication that the person portrayed held an elevated position in Nok society. The gender of the Nok artists is also unknown, but because the primary ceramists and clay sculptors across the continent have traditionally been women, Nok women may have sculpted these heads as well.

Form

3-dimensional representation of the head of a woman; hollow, baked clay; larger than lifesize.

Style

Stylized naturalism; very little attention to bone structure, smooth face, flattish nose with emphatic large nostrils; mouth open as if speaking or singing forming an oval; prominent, delicately curved thin, attached eyebrows; large bulging eyes with hollow pupils; carefully dressed hair; short, thick neck. Idealized beauty.

Meaning

Most simply, the representation of a beautiful woman according to Nok standards of beauty, or power, or authority.

Context

The geographical area occupied by the Nok culture corresponds with the northwestern portion of the modern state of Nigeria.

This head is just one of hundreds of examples, discovered at Nok sites. The presence of metal

(iron) and metallurgy among the Nok is a sign of technological sophistication. It is possible

that in addition to terracotta the Nok were also making art forms in metal, such as the later

culture of the area, the Igbo-Ukwu, of the 9 th - 10 th Century CE, and the later Ife (Ile-Ife)

#1 African History - The Nok

King

King:

Zinc-brass, 1′ 6 ½″ high

found in

Ife, Nigeria

Ife Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Just after the turn of the 19th century, the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius (1873–1938) “discovered” the sculpture of ancient Ife in the Lower Niger River region. Because of the refinement and naturalism of the statues and heads he saw, Frobenius could not believe that these sculptures were the work of local artists. As did most Europeans at that time, Frobenius had preconceived notions about the “primitive” nature of African art. Consequently, he attributed the Ife sculptures to ancient Greek artists. Other scholars traced the Ife works to ancient Egypt, along with patterns of sacred kingship that they also believed originated several thousand miles away in the Nile Valley. But excavations in and around ancient Ife, especially near the king’s palace, which stood at the center of the circular settlement, have conclusively established that ancient Nigerian sculptors were indeed the artists who made the extraordinary sculptures in stone, terracotta, and copper alloys found at Ife. Radiocarbon dating places these works as early as the 11thor 12th century. Most of the finds date to what archaeologists have dubbed the “Pavement Era” of the 12th to 14th centuries, when the Yoruba paved several rectangular areas of their capital at Ife with bricklike ceramic sherds. These paved precincts were probably ritual centers where the Yoruba displayed the images of their deceased rulers on altars. The sculptures served the kings in ceremonies of installation, in funerals, and in annual festivals reaffirming the sacred power of the ruler and the allegiance of his people. As is the case with the full-length portrait of the king illustrated here and the head from the royal palace complex, the Ife sculptors usually modeled both heads and bodies in a strikingly naturalistic manner, apart from blemishes or signs of age, which they intentionally omitted. Thus Ife style is lifelike but at the same time idealized. The artists portrayed most people as young adults in the prime of life and without any disfiguring warts or wrinkles. Some life-size heads, although still idealized, take naturalism so far as to give the impression of being individual portraits. This is especially true of a group of 19 heads cast in copper alloys that scholars are quite certain record the features of specific persons, although nearly all their names are lost. Several of the Ife heads have small holes above the forehead ) and around the lips and jaw, and were found with black beads. The perforations and beads suggest that the heads once had beaded crowns with veils, such as those known among Yoruba kings today, and perhaps human hair as well. Elaborate beadwork, a Yoruba royal prerogative, is also a key feature of the Ife royal statuette illustrated here. The hundreds of terracotta and copper-alloy heads, body parts and fragments, animals, and ritual vessels from Ife attest to a remarkable period of African art during which sensitive, meticulously rendered idealized naturalism prevailed. To this day, works in this style stand in vivid contrast to the vast majority of African objects, which show the human figure in many different, quite strongly conventionalized styles. Diversity of style in the art of a continent as vast and ancient as Africa should surprise no one, however.

Form

Standing male figure; 3-dimensional, cast metal: zinc/brass (bronze).

Style

Style: Naturalism. With proportions suggestive of dwarfism. However, this may be a stylistic convention (choice/rule of representation): emphasis on head, jewelry, belly, feet; short, stout legs. This is the most un-stylized, naturalistic style discovered among the tribal cultures of Africa. It is possible that real hair was used to increase the naturalism. (the patterns of holes that trace the beard and mustache of males, found on many pieces suggest so).

Meaning

A person of authority; solid presence, well nourished, youthful, wearing signs of wealth and status and carrying a horn of

medicine and a fly-whisk, symbols of the king. These images, of which there are hundreds, some

complete figures, others only heads, may be made in homage of deceased rulers. They may be portraits.

Some images show deliberate markings on the face as indicating the practice of decorating the

face with scarification. See 19.7a, and search for and examine

the image of Olokun in the British Museum.

#2 African History - Ile Ife

Context

Highly organized society capable of organizing resources and technological skills to create work of cast alloys. The skills seem to have evolved from Nok through Ife to be perfected by the Ife at this time. Kingship, Oni, was sacred. The Ife are considered by the Yoruba peoples to be the origin of all humankind, where the deities created the world.

Monolith with bird and crocodile

Monolith with bird and crocodile:

Soapstone, bird 1′ 2 ½″ high

found in

Great Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Explorations in Great Zimbabwe have yielded eight soapstone monoliths (sculptures carved from a single block of stone). Seven came from the royal hill complex and probably stood in shrines to ancestors. The eighth monolith, found in an area now considered the ancestral shrine of the ruler’s first wife, stands several feet tall. Some have interpreted the bird at the top as symbolizing the king or his ancestors. (Ancestral spirits among the present-day Shona-speaking peoples of the area take the form of birds, especially eagles, believed to communicate between the sky and the earth.) The crocodile on the front of the monolith may represent the wife’s elder male ancestors. The circles beneath the bird are called “eyes of the crocodile” in Shona and may symbolically represent elder female ancestors. The double- and single-chevron motifs may stand for young male and young female ancestors, respectively. The bird seems to be a bird of prey, such as an eagle, but this and other bird sculptures from the site have feet with five humanlike toes, rather than an eagle’s three-toed talons. The Great Zimbabwe birds are of no known species, and some scholars have speculated that the five-toed bird and the crocodile symbolize previous rulers who would have acted as messengers between the living and the dead, as well as between the sky and the earth."

Form

A monolith (single standing stone, soapstone) carved with 3-dimensional animal forms: at the top a large seated bird (today the official symbol of Zimbabwe). The angle of the photograph provided unfortunately distorts the length of the neck, which is long and columnar.

Style

Highly “stylized” and reminiscent of Egyptian art. Frontal, stiff, simplified forms with little interest in great detail.

Meaning

In the absence of written records scholars have interpreted this monolith (and there are others like it) as symbols of spiritual power associated with ruler-ship. The bird, the abstract “mask” with teeth, and the crocodile climbing up, or clinging to the front below the bird, perched like an Egyptian sphinx (See Chapter 3, 3-11), may be related to ancestral lineage (does this remind you of any other cultures and art forms we have encountered?)

Context

The monolith was found in a shrine dedicated to a queen.

Waist pendant of a Queen Mother Idia

Waist pendant of a Queen Mother Idia:

Ivory and iron, 9 ⅜″ high

found in

Benin, Nigeria

Benin Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " Among the masterworks of Benin art are the royal plaque already discussed and the altar honoring Oba Eresonyen (r. ca. 1735–1750) treated in the Introduction, both fashioned of brass. A third is the extraordinary ivory pendant, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, portraying Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie (r. ca. 1504–1550), under whom the Benin kingdom enjoyed great prosperity and expanded through a flourishing trade with the Portuguese. A nearly identical pendant, fashioned from the same piece of ivory, is in the British Museum. Idia had helped her son in warfare, and in return Esigie created for her the title of iy’oba (Queen Mother) and built her a separate palace and court. He and his successors also set up altars to their mothers on which they displayed bronze portraits of them. Esigie probably wore the pair of ivory pendants at his waist, making his mother’s face an integral part of his own identity. Both portraits are remarkable for their sensitive naturalism. On the Queen Mother’s crown are alternating bearded Portuguese heads and mudfish, symbolic references respectively to Benin’s trade and diplomatic relationships with the Portuguese and to Olokun, god of the sea, wealth, and creativity. The mudfish, equally at home on land and in the sea, also symbolized the dual human/divine aspect of the ruler. Another series of Portuguese heads adorn the lower part of the carving. In the late 15th and 16th centuries, the Benin people probably associated the Portuguese—with their large ships from across the sea, their powerful weapons, and their wealth in metals, cloth, and other goods—with Olokun, the deity they deemed responsible for abundance and prosperity."

Form

A plaque, a high relief sculpture in ivory of a woman’s face, meant to be worn as a pendant or belt decoration.

Style

After all that we have encountered so far, how would you describe the style?

Meaning

An idealized portrait of the queen mother, Queen Idia, the queen on King Esigie in honor of her role in obtaining the assistance of the Portuguese in trade and warfare. Iconography: the head-dress and neck décor, which resemble in some ways the elaborate lace ruff sword by royal and noble Europeans in the 16 th Century. The pattern, however, seems to alternate heads and mudfish, the messengers of Olokun, the (Ife) God of wealth and the sea.

Context

Mothers were especially honored with sculptural images by their sons in Benin culture.

Altar to the Hand and Arm (ikegobo)

Altar to the Hand and Arm (ikegobo):

Bronze, 1' 5 ½" high

found in

Benin, Nigeria

Benin Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Proportion concerns the relationships (in terms of size) of the parts of persons, buildings, or objects. People can judge “correct proportions” intuitively (“that statue’s head seems the right size for the body”). Or proportion can be a mathematical relationship between the size of one part of an artwork or building and the other parts within the work.

Form

The ikegobo is a round drum-like shape around which are figures in high relief and topped by a trinity of figures in 3-dimensional form. Cast bronze.

Style

Again, how would you describe it? How does it compare with Nok and Ife?

Meaning

Similarly, how do you “read” the iconography? What individual elements do you recognize? What do the size differences imply?

Context

How does it fit into what you are learning about Benin culture? Is it typical or atypical? Who is Sir William Ingram?

Saltcellar

Saltcellar:

Ivory, 1′ 4 ⅞″ high

found in

Sierra Leone

Sapi-Portuguese Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. "The Portuguese commissions included delicate spoons, forks, and elaborate containers usually referred to as saltcellars, as well as boxes, hunting horns, and knife handles. Salt was a valuable commodity, used both as a flavoring and as a food preservative. Costly saltcellars were prestige items that graced the tables of the European elite. Sapi sculptors meticulously carved the saltcellars from elephant tusk ivory, which was plentiful in those early days and was one of the coveted exports in early West and Central African trade with Europe. The ivories that the Sapi produced for export are a fascinating hybrid art form. Characterized by refined detail and careful finish, they are the earliest examples of African tourist art. Art historians have attributed the saltcellar shown here, almost 17 inches high, to the Master of the Symbolic Execution , one of the three major Sapi ivory carvers during the period. This saltcellar, which depicts an execution scene, is one of the artist’s best pieces and the source of the assigned name. A kneeling figure with a shield in one hand holds an ax (restored) in the other hand over another seated figure about to lose his head. On the ground before the executioner, six severed heads grimly testify to the executioner’s power. A double zigzag line separates the lid of the globular container from the rest of the vessel. This vessel rests in turn on a circular platform held up by slender rods adorned with crocodile images. Two male and two female figures sit between these rods, grasping them. The executioner and the other men wear European-style pants and have long, straight hair. The women wear skirts, and the elaborate raised patterns on their upper chests surely represent decorative scars. The European components of this saltcellar are the overall design of a spherical container on a pedestal and some of the geometric patterning on the base and the sphere, as well as certain elements of dress, such as the shirts and hats. Distinctly African are the style of the human heads and figures and their proportions, the latter skewed here to emphasize the head, as so often seen in African art. Identical large noses with flaring nostrils, as well as the conventions for rendering eyes and lips, characterize Sapi stone figures from the same region and period. Scholars do not know whether it was the African carver or the European patron who specified the subject matter and the configurations of various parts, but the Sapi works testify to a fruitful artistic interaction between Africans and Europeans during the early 16th century. Artistic exchanges between Europe and Africa became much more common in the late 19th and especially the 20th centuries. These developments and the continuing vitality of the native arts in Africa are examined in Chapter 37 . Contemporary African art in its global context is discussed in Chapter 31 ."

Form

European tabletop receptacle for salt as interpreted by Sapi artists. Elaborately carved base holding a round (basket-like) object that is the salt holder with a cover; at the top of the round hemisphere of the cover sits a warrior executing a captive.

Style

“Sapi” style: elongated forms; representational, symbolic scale, emphasis on the heads and large noses exaggerated in profile. Can be considered a hybrid style. It appears that the style is that of an artist whose other work has been identified in other museum collections, with his name “The Master of the Symbolic Execution,” derived from this piece.

Meaning

Clearly, this is a scene of some violence: the victim kneels offering his neck; the ground before the large armed seated warrior is covered with 6 severed heads. Why it is designated “symbolic execution” is curious. Because this is a commissioned work intended for a European audience, perhaps the emphasis is on meeting expectations and a taste for the exotic. The clothing of the figures of women and men has been identified as part native, part European.

Context

Interactive cultural influence. An early example of native artists adapting their skills, traditional subject matter, and possibly style, to please foreign patrons. Tourist art?

Reliquary guardian figure (mbulu ngulu)

Reliquary guardian figure (mbulu ngulu):

Wood, copper, iron, and brass, 1′ 9 1/16″ high

found in

Kota, Gabon

Kota Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. "The Kota of Gabon also produced reliquary guardian figures, called mbulu ngulu, but they differ markedly from the Fang bieri. The Kota figures have severely stylized bodies in the form of an open diamond below a wood head. The sculptors of these reliquary guardians covered both the head and the abstract body with strips and sheets of polished copper and brass. The Kota believed that the gleaming surfaces repelled evil. The simplified heads have hairstyles flattened out laterally above and beside the face. Geometric ridges, borders, and subdivisions add a textured elegance to the shiny forms. The copper alloy on most of these images is reworked sheet brass (or copper wire) taken from brass basins originating in Europe and traded into this area of equatorial Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Kota inserted the lower portion of the image into a basket or box of ancestral relics."

Form

Extremely abstracted human figure; carved wood covered over with thin copper plate. The figure has been (deliberately?) separated from the container on which it “stood.”

Style

Abstract, symbolic; exaggeration. Frontal.

Meaning

The “figure” with its large face and headdress is meant to instill fear and the presence of spiritual power. The open mouth with prominently displayed sharpened teed menaces and warns, appropriate actions that coincide with its function as a guardian figure, meant to protect the remains of ancestors. The metals shine of the copper sheets are prophylactic as well.

Context

Tan example of “incomplete retrieval.” Only the mbulu ngulu is collected, the “bones” of the ancestors are left behind. There could be many reasons for this separation. How would you describe it?

Nail figure (nkisi n’kondi)

Nail figure (nkisi n’kondi):

Wood, nails, blades, medicinal materials, and cowrie shell, 3′ 10 ¾″ high

found in

Democratic Republic of Congo

Kongo Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Among the most distinctive African sculptures of the 19th century are the Kongo power figures called nkisi n’kondi , such

as the standing statue illustrated here, which depicts a man bristling with nails

and blades. These images, consecrated by trained priests using precise ritual formulas, embodied

spirits believed to heal and give life, or sometimes to inflict harm, disease, or even death.

Each figure had its specific role, just as it wore particular medicines—here protruding from

the abdomen, which features a large cowrie shell. The Kongo also activated every image differently.

Owners appealed to a figure’s forces everytime they inserted a nail or blade as if to prod the

spirit to do its work. People invoked other spirits by repeating specific chants, rubbing the

images, or applying special powders. The roles of power figures varied enormously, from curing

minor ailments to stimulating crop growth, from punishing thieves to weakening enemies. Very

large Kongo figures, such as this one, which is nearly 4 feet tall, had exceptional ascribed

powers and aided entire communities. Although benevolent for their owners, the figures stood

at the boundary between life and death, and most villagers held them in awe. Compared with the

sculptures of other African peoples, this Kongo figure is relatively naturalistic, although the

carver simplified the facial features and magnified the size of the head for emphasis."

Form

A free-standing human figure; frontal, simple but effective in conveying power and authority: the broad, open chest, hands on the hips, frank, forward jutting chin. Wood, shell.

Style

Highly stylized; muscular body.

Meaning

Nkisi n’kondi is a special type of spiritual figure intended to channel healing powers or inflict harm (similar to voodoo

practices that arose out of African tribal religions brought to Haiti from West Africa). To create

the magic healing powers the figure is “invested” with a secret recipe of power-building materials

concocted by a shaman/priest and ritually sealed in the navel area. Each separate ritual event

is “recorded” by the piercing of the figure with a sharp metal object, which remains. May be

called a “fetish.”

Power Figure (Kongo peoples)

Context

Ritual, group belief system. No longer in circulation, but still possessing its “investment” package. How did it end up in Detroit?

Seated Couple

Seated Couple:

Wood, 2′ 4″ high

found in

Mali

Dogon Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The Dogon live in the Bandiagara escarpment south of the inland delta region of the great Niger River in what is today Mali. Numbering around 800,000, spread among hundreds of small villages, the Dogon practice farming as their principal occupation. The Dogon statuette illustrated here depicts a human couple, one of the most common themes in African art. This Dogon example is, however, of exceptional quality. It dates to the early 19th century and may have served as a portable shrine or altar, although contextual information is lacking. Interpretations vary, but the image vividly documents primary gender roles in traditional African society. The man wears a quiver on his back. The woman carries a child on hers. Thus the man assumes a protective role as hunter or warrior, the woman a nurturing role. The slightly larger man reaches behind his mate’s neck and touches her breast as if to protect her. His left hand points to his genitalia. Four stylized figures support the stool on which they sit. They are probably either spirits or ancestors, but the identity of the larger figures is uncertain. The strong stylization of Dogon sculptures contrasts sharply with the organic, relatively realistic treatment of the human body in Kongo art. The artist who carved the Dogon couple based the forms more on the idea or concept of the human body than on observation of individual heads, torsos, and limbs. The linked body parts are tubes and columns articulated inorganically. The carver reinforced the almost abstract geometry of the overall composition by incising rectilinear and diagonal patterns on the surfaces. The Dogon artist also understood the importance of space, and charged the voids, as well as the sculptural forms, with rhythm and tension."

Form

A Seated man and woman. 3-dimensional.

Style

Stylized by extreme elongation of form; simple columnar shapes for torso and limbs; blocklike feet; long faces with noses in the shape of “arrows” (a characteristic of the Dogon style. Static, but with a small sense of movement in the tilt of the heads.

Meaning

Ancestral couple, male and female, husband and wife, mother and father. Equally sized, suggestive of complementarity and harmony; the male possesses the female? Shows she belongs to him? Embraces her? With his other hand protects his genitals; (See also Baule couple, Shapter 37, figure 7, “bush spirits.”

Context

Couple (Dogon peoples)

Kept in private shrine.

Beautiful Lady” dance mask

Beautiful Lady” dance mask:

Wood, 1′ ½″ high

found in

Ivory Coast

Senufo Culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The Senufo of the western Sudan region in what is now northern Côte d’Ivoire have a population today of more than a million. They speak several different languages, sometimes even in the same village. Not surprisingly, there are many different Senufo art forms, including woodcarving and mask making, all closely tied to community life. Senufo men dance many masks, mostly in the context of Poro, the main association for socialization and initiation—a protracted process taking nearly 20 years for men to complete. Maskers also perform at funerals and other public spectacles. Large Senufo masks are composite creatures, combining characteristics of antelope, crocodile, warthog, hyena, and human: sweeping horns, a head, and an open-jawed snout with sharp teeth. These masks incarnate both ancestors and bush powers that combat witchcraft and sorcery, malevolent spirits, and the wandering dead. They are protectors who fight evil with their aggressively powerful forms and their medicines. At funerals, Senufo maskers attend the corpse and, by dancing the masks, they help expel the deceased from the village. This is the deceased individual’s final transition, a rite of passage parallel to that undergone by all men during their years of Poro socialization, in which masks also play a role. When an important person dies, the convergence of several masking groups, as well as the music, dancing, costuming, and feasting of many people, constitute a festive and complex work of art that transcends any one mask or character. Some Senufo men also dance female masks. The most recurrent type has a small face with fine features, several extensions, and varied motifs—a hornbill bird in the illustrated example —rising from the forehead. The men who dance these feminine characters also wear knitted body suits or trade-cloth costumes to indicate their beauty and their ties with the order and civilization of the village. They may be called “pretty young girl,”“beautiful lady,” or “wife” of one of the heavy, terrorizing masculine masks appearing before or after them."

Senufo Beautiful Lady mask

See other examples.

Form

Complex combination of forms, a double face and a hornbill bird, exaggeration, abstraction.

Style

Distortion, abstraction, yet still representation.

Meaning

Symbolized a typical Senufo woman’s complexity and unpredictability; moods, desires, etc.

Context

The mask is part of a larger whole, and entire costume that covered the entire body and which was worn by the men in the Poro Society whose duty it is to train young men in social responsibility and behavior.

D’mba mask

D’mba mask:

Wood and brass, 4′ 4″ high

found in

Guinea

Baga culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows.

"

Until the early 20th century, when Muslim missionaries suppressed the custom, the Baga of northern Guinea danced a masquerade

in honor of the Mother of Fertility to protect pregnant women and promote abundant harvests.

(The government restored the practice in 1984.) The masks that the Baga dancers wear, one of

which was in the collection of Pablo Picasso, are called d’mba and take the form

of the head and torso of a woman. Carved from a single piece of wood, the masks

have four “legs” so that Baga men can rest them on their shoulders. The dancer thus appears about

8 feet tall and towers over all others in the community. The d’mba’s legs provide stability for

the heavy masks, which often weigh as much as 80 pounds. The legs are hidden beneath a long raffia

skirt, which also disguises the dancer’s identity. Holes between the mask’s prominent breasts

enable the wearer to see. The breasts themselves are flattened because they are the breasts of

an ideal woman who has suckled countless babies. The face has a large nose, and the forehead

and cheeks as well as the breasts feature scarification patterns. The Mother of Fertility masks

are danced at weddings, funerals, and harvest festivals exclusively by men, despite the identity

of the d’mba."

See the complete mask, which includes the raffia and cloth costume.

The Artistry of Tlingit Weaving

Watch first and second dances.

Form

D’mba, or Great Mask. A standardized type of mask produced with individual variations. Head and torso, the lower “legs” are supports for the mask and rest on the shoulders of the dancer.

Style

Abstraction of the female head and torso; deformation, elongation, exaggeration. The sides of the head and chest are often embellished with carved details of patterns of scarification. The style and form are distinct and immediately recognizable.

Meaning

In the Baga Culture this mask is worn by male dancers in a celebration of female fertility in the form of the Mother of Fertility. The flat breasts symbolize a mother of many, whose breasts have suckled many children, an older, mature woman.

Context

Muslim missionaries suppressed these indigenous cultural practices, but they were restored in 1984. The masked D’mba dancers perform at many significant events in past and contemporary Baga life.

Female mask

Female mask:

Painted wood, 1′ 2 ½″ high

found in

Sierra Leone

Mende culture

Your eBook, Kleiner Art Through the Ages, 15th edition, describes the image as follows. " The Mende and neighboring peoples of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea are distinctive in Africa because the women perform masquerades. However, the masks and costumes that the women wear conceal their bodies from the audience attending their performance. The Sande society of the Mende controls the initiation, education, and acculturation of Mende girls. Women leaders who dance the Sande masks serve as priestesses and judges during the three years that the women’s society controls the ritual calendar (alternating with the men’s society in this role), thus serving the community as a whole. Women maskers, who function as initiators, teachers, and mentors, help girl novices with their transformation into educated and marriageable women. Sande women associate their Sowie masks with water spirits and the color black, which the society, in turn, connects with human skin color and the civilized world. The women wear these helmet masks on top of their heads as headdresses, with black raffia and cloth costumes to hide the wearers’ individual identities while personifying the spirits during public performances. Elaborate coiffures, shiny black color, dainty triangular-shaped faces with slit eyes, rolls around the neck, and real and carved versions of amulets and various emblems on the top commonly characterize Sowie masks. These symbolize the adult women’s roles as wives, mothers, providers for the family, and keepers of medicines for use within the Sande association and the society at large. Sande members commission the masks from male carvers, with the carver and patron together determining the type of mask needed for a particular societal purpose. The Mende often keep, repair, and reuse masks for many decades, thereby preserving them as models for subsequent generations of carvers."

Mende

Mende culture

Images of Mende culture

Form

Uniform shape shared with little variation by all masks of this design, which represents: Woman. High forehead, beautifully woven, braided hair, head like a chrysalis where the jaw meets the neck; downcast eyes, tiny nose, even tinier mouth. Encircled by holes for raffia.

Style

Deliberate abstraction and deformation of female face and neck to signify cultural ideals: smooth skin, beautiful hair, the ideal of womanhood.

Meaning

Sowei Mask of the Sande Society: this is the spirit of the water goddess (Sowei) Water imagery is represented by the turtle on top of the head; the neck swells are like waves in the water. The water surface is disturbed when the goddess emerges… The woman is wise, elegant, serene, and self-effacing.

Context

The mask is worn by women dancers, a rare exception to the general rule of men doing the work of dancing. This is women society, parts played by women; the spirit is brought into society for special events involving women, especially female circumcision.