Origins and History

|

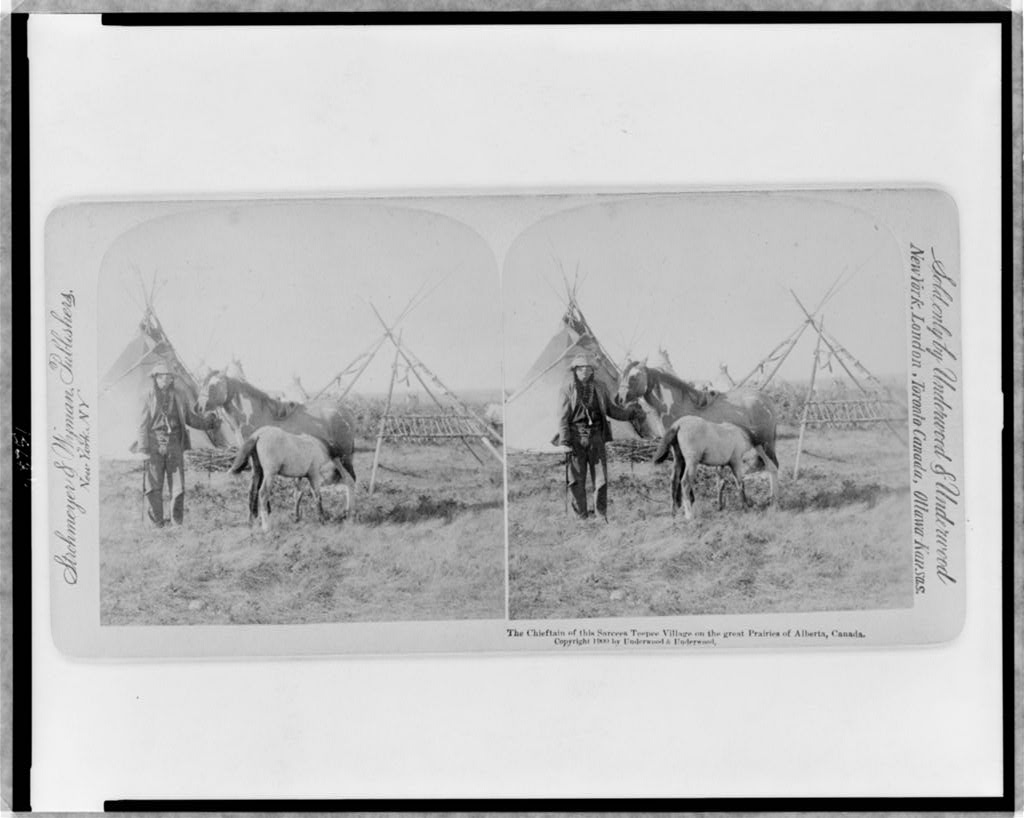

The Navajo and Apache are related to the northern Athapaskan Indians, such as the Sarcee tribe from Canada, shown here. Note the similarity in dwelling styles. Source - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=97507231 The Navajo and the Apache are the only Southwestern Indians whose languages belong to the Athapaskan language family; other Athapaskan speakers live far to the north in Canada, Alaska, and on the Pacific Coast. Evidence suggests that about one thousand years ago some of the Canadian Athapaskans begin to migrate southward, eventually arriving in northwest New Mexico at about 1400 A.D.

During this long trek the Athapaskans—who in Canada had lived as hunter-gatherers adapted to a cold climate— adjusted to the environments they encountered by readily adopting new technologies along the way. This resilience—the willingness to change and adapt while retaining core aspects of their identity-- remains a key trait of the Navajo today. |

|

The Athapaskans entered the American Southwest in small, extended family groups. These early Athapaskans shared a similar hunting and gathering lifestyles. Over time, these groups spread into different ecological niches and became differentiated from one another. Some groups remained in northern New Mexico and adopted farming from the puebloan cultures; it is their descendants that are the Navajo. When the Spaniards arrived in the early 16th century, the Diné were a semi-nomadic people living in northern New Mexico in the homeland that they called Dinetah. These early Diné lived in extended family groups and alternated their time between hunting and gathering and farming activities. However, it wasn't until after Reconquest of 1692 that the culture we identify as "Navajo" crystallized. In Module 2, we learned about the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in which the Pueblo Indians defeated the Spanish and drove them from northern New Mexico. We also learned about the Spanish Reconquest of the region twelve years later, when Spaniards were able to regain control of this territory. The Diné participated in the Pueblo Revolt and, when the Spaniards returned to defeat the Puebloans, allowed Puebloan refugees to settle in their territory. It was during this post-Reconquest period, when the two groups of people lived side by side, that the Diné incorporated certain puebloan practices and beliefs into their culture and the distinctive Navajo culture emerged.

Simon Canyon Pueblito, a Navajo and Puebloan site occupied after the Re-conquest. The Navajo borrowed the idea of masonry structures from the Pueblo Indians to build towers that could be used as lookouts. To avoid Spanish reprisals, these post-Reconquest settlements were commonly built in defensive locations. Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pueblito_in_Simon_Canyon.jpg |

|

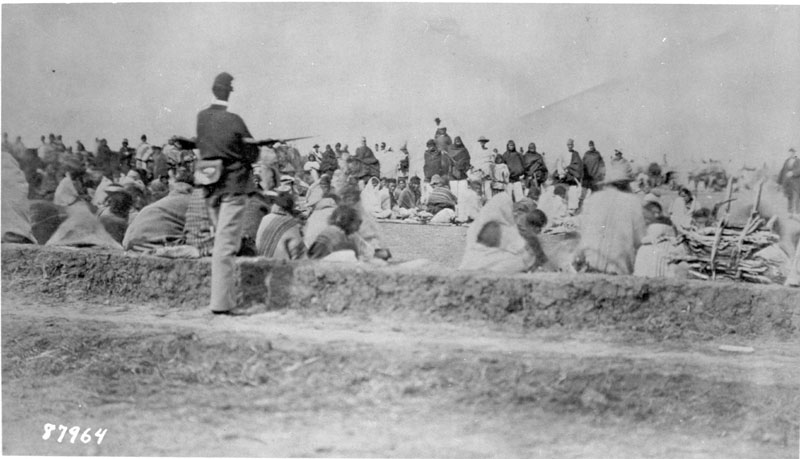

In the 1700s the Navajo were forced to expand out of their homeland due to droughts and raiding from Ute Indians. Initially, the movement out of Dinetah was peaceful, but by the middle 1800s Anglo settlers were losing massive numbers of livestock to Navajo raiding. When the region came under U.S. jurisdiction in 1848, the settlers demanded protection. When Brigadier General James Carleton was appointed military commander over the region in 1862 he decided the only way to resolve the problem was to relocate the Navajo out of the region. In April of 1863, he proclaimed that the Navajo had until July 20 to turn themselves and be relocated to Bosque Redondo, an Indian Reservation on the Pecos River. The next fall, under the direction of General Carlton, a reluctant Kit Carson initiated a "scorched earth campaign," in which Navajo livestock were confiscated and their fields, houses, and orchards burned down. Later that winter large numbers of starving Navajo begin to turn themselves in. Ultimately, some 9000 Navajo surrendered and made the long, 300+ mile trek from Fort Defiance to the Bosque Redondo. During this trek, which was made on foot and in winter, the Navajo faced unbelievable hardships and many died from exposure to the cold and from starvation and exhaustion. Those who could not keep up, including pregnant women who went into labor, were shot by soldiers. This trek, known as the Long Walk, remains deeply etched in the collective memories of the Navajo today. The Navajo were imprisoned at Bosque Redondo for four years, at a cost to the U.S. government of two million dollars. Conditions on the reservation were horrendous and resulted in the deaths of many more Navajo from dysentery, small pox, and poor living conditions. By all accounts, the Bosque Redondo effort was considered a massive failure. After numerous newspaper stories were run detailing the suffering of the Navajo and the economic costs of the policy, Carleton was relieved of his command and the Navajo given a reservation (within their original homeland) in 1868.

Navajos at Bosque Redondo under guard, ca. 1864-1868. Source - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hweeldi3.jpg

|

|

Upon their return to their homeland the Navajo were given 14,000 sheep by the U.S. government; by 1892, these herds had expanded nearly one hundred fold. As their herds grew the Navajo population also grew, and several additions were made to their reservation to accommodate their increasing need for space. In addition to sheepherding, the Navajo entered the market economy by producing items such as woven blankets and silver jewelry which were in demand by the growing tourist economy. In short, whereas the Navajo returned from their incarceration at Bosque Redondo an impoverished people, in only a few decades they were able to transform themselves into a thriving and economically independent people. This economic independence was shattered in the 1930s as a result of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) stock reduction program. In 1933, the BIA determined that as much as two-thirds of the Navajo range had been destroyed by overgrazing and instituted a program to thin the herds against the wishes of the Navajo. The inhumane methods used to kill off the herds and the insensitivity in how the program was instituted angered the Navajo and, like the Long Walk, is remembered with bitterness today. The stock reduction program, along with the Great Depression, ushered in a period of dependence on the wage economy and welfare for the Navajo people. In World War II, the military enlisted Navajo to transmit secret communications using their native language. For those words which had no Navajo equivalent, Navajo words were assigned new meanings. For example, the Navajo word for "egg" was used for "bomb," and the Navajo word for "hummingbird" was used to indicate "fighter plane." The code created and used by the 420 Navajo Codetalkers, as they came to be known, is the only code that was never broken by the Japanese.

Dan Akee, World War II Veteran and Navajo Code Talker, being honored during Native American Heritage Month. National Park Service photograph taken by Erin Whittaker on November 18, 2010. Source - http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a6/Dan_Akee%2C_Navajo_Code_Talker.jpg |

Click on next page to continue.