History

|

The history of the Apache people is a history of conflict. When the Spaniards arrived in Arizona and New Mexico, Apache raiding aimed at neighboring Indian tribes was a commonplace occurrence. With the introduction of the horse the Apache easily expanded their raids to include Spanish settlements. Raiding led to retribution, which quickly escalated into a cycle of conflict and warfare that only intensified when the Apache territory came under Mexican control.

When the Americans acquired the Apache homeland in the 1850s, they inherited this cycle of conflict. Determined to end the bloodshed, the federal government initiated a campaign to relocate all Apache to reservations. This was a frustrating process for the U.S. Army, as peace treaties signed by various headmen would be broken promptly by other Apache. The problem was created by a lack of understanding on the part of Americans of Apache social organization; Americans failed to appreciate that most headman could speak for, at most, only a few dozen Apache. Regardless, by 1868 nearly all of the Apache had been subdued and relocated except the Chiricahua.

The Chiricahua resistance was initially headed by Cochise, who became angered when his uncle Mangas Coloradas was tortured and murdered in 1863 after being convinced to meet with the U.S. Army for peace talks. Over the next few years, Cochise was to become a widely respected leader, eventually gaining the following of all of the Chiricahua bands. Cochise thus was the first and (until modern times) the only Apache leader to unify the entire tribe and to gain leadership over all of its people. Cochise successfully waged war against the U.S. until 1872, when he was persuaded to surrender in exchange for a Chiricahua Apache reservation in Arizona. Conditions were not good on the reservation and most of the Apache were unhappy, but under the persuasive leadership of Cochise they agreed to remain there.

|

Cochise's Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains, southern Arizona. Cochise was able to hide out in these mountains until 1872 to avoid capture. Source - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Cochise_Stronghold#/media/File:Owl_rock_-_Cochise_Stronghold_East.jpg

|

|

Unfortunately for both the U.S. Army which oversaw the reservation and for the Chiricahua Apache, Cochise died in 1874. Upon his death, tensions on the reservation increased which led the federal government to relocate the Chiricahua to the San Carlos reservation, which at that time housed primarily members of the Western Apache tribe. Conditions on that reservation were even worse, and in 1881 a group of Chiricahua headed by Geronimo escaped.

This marked the beginning of the Apache Wars, which would be the last of the Indian wars to be fought in our country. It was also one of the bloodiest, with Geronimo soon earning the reputation of a vicious killer who would kill anyone, including women and children, found in his path. Inflamed by lurid newspaper accounts, most Americans at the time feared and hated him.

The Apache themselves viewed him with mixed emotions; while they respected him for his military prowess and fearlessness, he was considered too hotheaded to be accepted as chief. Thus, Geronimo was never a chief but instead was considered a military leader.

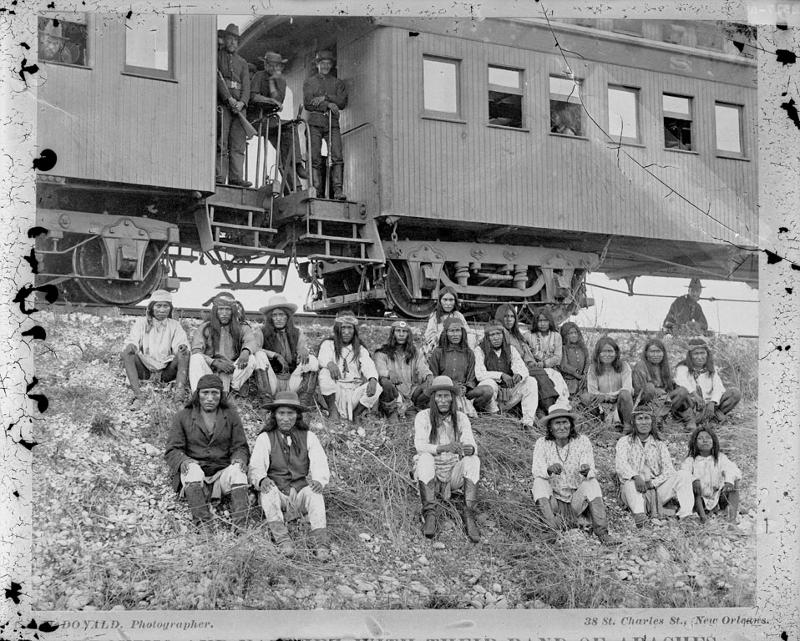

Geronimo became the most hunted man in the country, with his small band of 39 fugitives ultimately being pursued by some 5000 American troops and 3000 Mexican troops. To avoid capture the fugitives found themselves constantly on the move. With the help of some Chiricahua scouts, Geronimo's band finally was found and convinced to surrender on September 8, 1886. Geronimo's band—along with all other Chiricahua, including those that had remained on the reservation and those that had helped the Army find Geronimo—were classified as prisoners and sent to facilities located in Florida and Alabama where nearly one quarter of them died.

In 1894 they were relocated once again to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where conditions improved. It wasn't until 1913, however, that they were freed as prisoners of war. At that point they were given the choice of remaining near Fort Sill or moving to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico. Most moved to New Mexico but a few elected to remain near Fort Sill, where their descendants today are known as the "Fort Sill Apache."

|

Geronimo and his followers being taken as prisoners to Florida after their surrender, 1886 Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/baegn/gn_02517a.jpg |

|

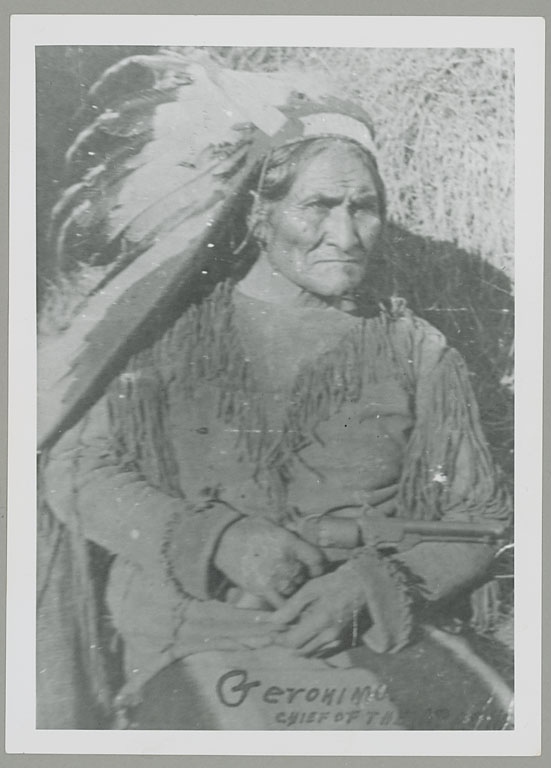

Geronimo, once the most feared and hated man in American, became transformed in the American imagination into a folk hero.

Although still technically a prisoner, from the late 1890s until his death in 1909, he was allowed by the federal government to make public appearances where he would sell photographs of himself. However, he was never granted his lifelong wish to be able to return to his homeland in Arizona.

Photograph of Geronimo, taken at a fair in 1905. In his later years, Geronimo was considered something of a folk hero and appeared at fairs and Old West shows where he sold photographs of himself and souvenirs Source - http://sirismm.si.edu/naa/24/apache/02021900.jpg

|

Today, the fascination with Geronimo continues. Rumors persist that his bones were dug up by pranksters (including Prescott Bush, father of the first President George Bush) in 1918 and given to the secret Skull and Bones society associated with Yale University.

The Apache sued for the return of these remains in 2009 but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence in 2010.

The same year that this lawsuit was filed, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring Geronimo for his "extraordinary bravery, and his commitment to the defense of his homeland, his people, and the Apache ways of life." And, in 2011, Geronimo's name served as the code name for the operation to get Osama Bin Laden.

|

|

|

|